A tiny electric charge on bees can trigger flowers to emit a fragrance, according to a UK lab study. It appears some plants use this to signal the presence of their flowers to insects to increase their chances of being pollinated.

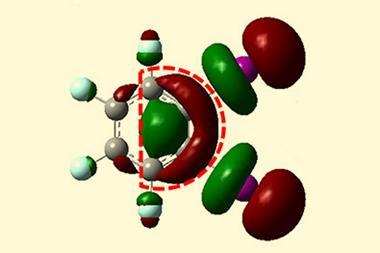

Bumblebees visiting petunia (Petunia integrifolia) flowers were found to trigger the release of benzaldehyde. Volatile emissions also rose when Clara Montgomery, who carried out the research at the University of Bristol, touched the potted flowers with a charged ball of nylon, but they didn’t when she used an electrically grounded metal rod. Bee antennae were also shown to be responsive to benzaldehyde at those emission levels.

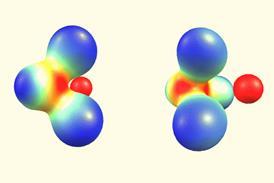

Bumblebees generate a tiny positive charge of around 120 picoCoulombs (pC) as they fly through air. This charge likely helps them gather pollen, which tends to be negatively charged. Bees have antennae and hairs that can sense weak electric fields near flowers and this helps them determine whether a flower was visited recently. The new research suggests that plants also tap into this electrostatic information.

Typically, at least 600 to 700pC was necessary to trigger volatile emissions from the petunias in the experiment. ‘We think that the electric charge on bees is contributing to or causing the increase in volatile emissions, but it might require multiple bees,’ says Montgomery. She estimates that perhaps five or six visits is sufficient.

Benzaldehyde is a simple aromatic aldehyde with an almond-like odour and the main constituent of petunia fragrance. Another species in the same experiments, snapdragons, showed no detectable increase of volatile chemicals when exposed to electrical charge.

‘We already knew that bees carry electrical charge and that the electrical field of bees can facilitate pollen transfer between bees and flower,’ says József Vuts, a chemical ecologist at Rothamsted Research, UK, also involved in the research. ‘We wanted to know if the charge itself can influence the interaction between the flower and the insect in other ways.’

Natalie Hempel de Ibarra, a pollination scientist at the University of Exeter, says ‘flowers cannot spend endless energy on advertising to pollinators, so it is intriguing that they might be influenced by this weak electric field when a pollinator is close to or visiting a flower’. She says that ‘we need to pay more attention to what is going on during a flower visit’. Greater understanding of plant-pollinator communications might even allow improvements in flower fertilisation, she adds.

Our reliance on bees for pollination means ‘it’s really essential that we understand the relationship between plants and pollinators and the little nuances,’ adds Montgomery.

Lots of factors affect bee charge, such as the weather, vehicle exhaust pollution and powerlines. ‘It’s important we understand the communication between plants and pollinators and that we don’t jeopardise that relationship,’ concludes Montgomery, now at Harper Adams University, UK.

‘The idea that flowers aren’t just passive players in the market economy of pollination systems is a fascinating one: that flowers tailor signals and rewards to pollinator behaviour,’ and economise their investments in signals and rewards, comments Lars Chittka, behavioral ecologist at Queen Mary University of London. ‘We need to test this in more plant species to see if it is a widespread phenomenon, and to further investigate the mechanisms.’

References

C Montgomery et al, Sci. Nat., 2021, 108, 44, DOI: 10.1007/s00114-021-01740-2

No comments yet