Intellectual property theft has become a growing worry for the US government. There is concern that US universities, government research facilities and companies are vulnerable to theft of sensitive information by China and other hostile foreign governments. Amid fears that the US is in danger of losing its technological edge over competitors, the government is seeking to crackdown on Chinese government programmes operating in the country.

The US Justice Department (DOJ) announced just before Christmas that it had reached a $5.5 million (£4.24 million) settlement with the Michigan-based Van Andel Research Institute over allegations that it failed to disclose that the Chinese government was funding two of its researchers.

Between 2012 and 2019, the non-profit biomedical research and education organisation received grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to fund the two researchers in question. However, the DOJ alleges that the Van Andel Research Institute never divulged to the NIH that the scientists also had foreign research funding. The DOJ accuses Van Andel of making ‘factual representations to NIH with deliberate ignorance or reckless disregard for the truth regarding the Chinese grants’. Van Andel admits no liability, and notes that both the professors involved have resigned.

Van Andel is not the only US research institute in hot water for allowing its scientists to accept Chinese funding. The Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Florida has also fallen foul of these rules. Its president and chief executive, Alan List, and director, Thomas Sellers, both resigned on 18 December over their participation in China’s ‘Thousand Talents’ programme, as well as participation by at least four other faculty members. The other four researchers also lost their jobs. For a decade, the Chinese government has been operating the Thousand Talents programme to recruit science and technology experts from western universities and research institutes to work in China.

A report from Moffitt earlier this month to Florida state legislators, who are investigating the issue, said the faculty members accepted personal cash honoraria and travel benefits during their visits to China, without reporting these to Moffitt, and that they also opened personal bank accounts in China to receive these unreported funds. There is no evidence, however, that intellectual property was stolen or that research or patient care was compromised.

200 recruitment programmes

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has described how the Chinese government oversees expert recruitment programmes, such as the Thousand Talents, offers lucrative financial and research benefits to recruit individuals working and studying outside of China who possess access to, or expertise in, high-priority research fields. The agency estimates that China’s government has more than 200 similar initiatives, some of which US taxpayers are unwittingly financing.

A report released by a Senate homeland security and governmental affairs subcommittee in November found that such talent recruitment programmes have ‘strategically and systematically acquired knowledge and intellectual property from researchers and scientists’ in the US.

As a talent plan recruit, he quit his job, bought a one-way ticket to China, and was caught at the airport with a copy of the company’s proprietary algorithm

John Demers, US Justice Department

The congressional investigation revealed that members of these programmes worked on sensitive research and had security clearance at US national laboratories, which are considered a cornerstone of the country’s innovation ecosystem. One individual, for example, used intellectual property created during work in a national lab and filed for a US patent under the name of a Chinese company, the Senate report noted. Another member, who was a postdoctoral researcher at a national lab, downloaded more than 30,000 files from a national lab right before returning to China.

The analysis indicates that the US Department of Energy, which oversees the nation’s 17 national labs, is particularly attractive to China’s recruitment plans. This agency is subject to the most penetration attempts for technology transfers because of its prominent role in advanced R&D, particularly in energy and nuclear weapons development.

The Senate report also noted that the NIH started reviewing research awards with connections to Thousand Talents last year. Consequently, it found some grants failed to disclose foreign funding and associations, and the agency also discovered thefts of intellectual capital and property, as well as violations of the peer review process. The NIH, which supports more than 300,000 researchers at 2500 institutes, has reportedly identified 250 researchers as ‘individuals of possible concern’, of which about 30% served as a peer reviewer over the past two years. The congressional report criticised the NIH for relying on research institutions to solicit disclosures of financial conflicts by employees with grants.

No comprehensive strategy

The Senate investigation also found that the National Science Foundation (NSF) has taken several steps – deemed insufficient – to try to mitigate the risk from Chinese talent programmes. In July, the agency prohibited employees from joining such foreign schemes, but that policy apparently doesn’t apply to the more than 40,000 NSF-funded researchers who conduct research and are the most likely targets for these schemes.

Overall, the Senate subcommittee reviewed the efforts of seven US federal agencies to address concerns about Chinese talent recruitment and the harm they do to the US research enterprise, and concluded that there is no comprehensive government strategy to combat this threat. The report urges US universities and US-based researchers to take responsibility. ‘If universities can vet employees for scientific rigour or allegations of plagiarism they also can vet for financial conflicts of interests and foreign sources of funding,’ the congressional report asserted.

More recently, analysis released in December by the US government’s elite science advisory group Jason reached similar conclusions. ‘Actions of the Chinese government and its institutions that are not in accord with US values of science ethics have raised concerns about foreign influence in the US academic sector,’ Jason determined, after reviewing classified and unclassified evidence. Nevertheless, Jason said the scale and scope of the problem remain ‘poorly defined’, and suggested academic leadership, faculty and front-line government agencies work together to gain a common understanding of foreign influence.

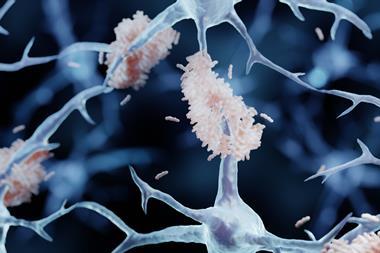

Hard evidence on extent of the problem is lacking, but several high profile cases provide some pointers. Most recently, Chinese graduate student Zaosong Zheng, who was conducting research at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston, was arrested at an airport in December with 21 hidden vials of biological samples stolen from the lab where he worked, according to Boston news site Universal Hub. Zheng, who was a doctoral student at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou in China, told authorities that he had planned to take the samples to his lab at Sun Yat-sen and replicate the Beth Israel research and, if successful, to publish a paper in his name.

China ties

Another Chinese national, Haitao Xiang, was indicted by a grand jury in Missouri in November for economic espionage and theft of trade secrets, among other charges. Xiang worked as an imaging scientist for Monsanto – the US agrochemical company acquired by Bayer last year – from 2008 to 2017. At Monsanto, he was developing a digital, online farming software platform to help farmers collect, store and visualise critical agricultural field data to increase agricultural productivity. Xiang was arrested in June 2017 attempting to leave the US with a micro SD card containing Monsanto trade secrets.

‘Within a year of being selected as a talent plan recruit, he quit his job, bought a one-way ticket to China, and was caught at the airport with a copy of the company’s proprietary algorithm before he could spirit it away,’ stated John Demers, the Justice Department’s assistant attorney general for national security. ‘Xiang promoted himself to the Chinese government based on his experience at Monsanto.’

A few months earlier, a Chinese-born tenured chemistry professor at the University of Kansas named Feng ‘Franklin’ Tao was indicted for fraud after it was revealed that he was working under a full-time contract for a Chinese university while conducting his academic research in the US.

Back in May, Turab Lookman, a long-time research physicist working on accelerated materials discovery at Los Alamos national lab in New Mexico, was arrested and charged with lying about his participation in China’s Thousand Talents programme. The Indian-born naturalised US citizen pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial.

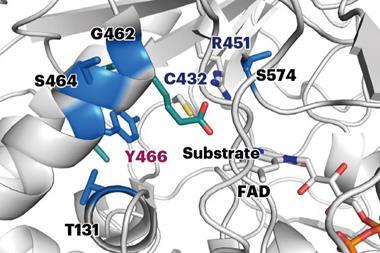

Last year two former GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) scientists admitted to stealing trade secrets. In September 2018, Tao Li pled guilty to theft of GSK’s proprietary information for Chinese pharmaceutical start-up Renopharma, which he helped co-found. Li’s colleague and co-conspirator, Yu Xue, pled guilty to similar charges the previous month.

UK at risk

Despite high profile cases, there is concern that the US government may be unfairly targeting Chinese–Americans. A recent report by the US-based international network Scholars at Risk warned that government officials, particularly in the US, have made ‘sweeping allegations’ that overseas Chinese scholars and students engage in scientific espionage and intellectual property theft. ‘In response to these allegations, government officials have proposed or taken actions that threaten the ability of overseas Chinese scholars and students to study, engage in academic work and feel welcomed in their host countries and institutions,’ Scholars at Risk said.

The US State Department adopted new restrictions on overseas Chinese students and researchers in June 2018, which called for the shortening of student visas in certain high-tech areas from five years to one. These new rules also required new clearances from multiple agencies for Chinese citizens seeking visas to work for certain companies deemed to need ‘higher scrutiny’.

The UK faces similar problems. The government’s Centre for the Protection of National Insfrastructure (CPNI) is urging UK universities to ensure that funding partnerships with foreign governments such as China do not allow universities to become ‘an easy route’ for them to gain access to valuable research data or intellectual property.

‘Hostile state actors are targeting UK universities to steal personal data, research data and intellectual property, and this could be used for their own military, commercial and authoritarian interests,’ CPNI warned in a statement. The agency notes that individual researchers may be targeted by a hostile state actor, or even by an academic institution to undertake research of strategic benefit to that country.

The National Cybersecurity Centre has said that UK universities conducting high-end research and generating high value intellectual property will ‘almost certainly remain a target for state-sponsored espionage’. The agency predicts that foreign espionage will ‘continue to pose the most significant threat to the long-term health of both universities and the UK itself’.

No comments yet