The father of modern electrochemistry talks baseball, the segregation era, and why your students are the most important thing

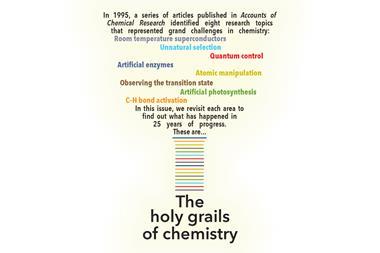

Allen Bard is a chemistry professor at the University of Texas at Austin, US, who helped assemble the holy grails of chemistry for Accounts of Chemical Research 25 years ago. Considered by many to be the ‘father of modern electrochemistry’, he is known for his pioneering work on scanning electrochemical microscopy, electrochemiluminescence and photoelectrochemistry.

I grew up in New York and it was interesting times, because first, I was born during the Great Depression, and then, right after that, the second world war started. But for a child, New York was a very good place. It was exciting. I would go down to museums by subway, even when I was very small, every weekend. It was a real playground of anything you wanted.

I was a huge fan of the New York Yankees. If I could get seats at a game, that was a big bonanza for me. I’d sit in the bleachers, and I’d stand outside the stadium and wait for the players to come out and ask them to sign my scorecard. When I moved to Texas many years later, my mother threw out everything I had accumulated – I had Yogi Berra’s autograph!

Somewhere I learned about electrolysis and that if you put batteries on to metal electrodes, you could get hydrogen. What was limiting to me was that I couldn’t afford the batteries. But then I learned you could make a power supply out of vacuum tubes. I got a hold of an old radio, took out the power supply section and used that to make hydrogen and oxygen. That got me thinking that, wow, you can put two fields together – the field of electricity and the field of chemistry. That fascinated me.

During the second world war, car production ceased all over the world, the car manufacturers were making tanks and half-tracks. But after the war, they started making cars again, and I had an uncle in Minnesota who was a car dealer. We went out and bought a 1947 Plymouth. People would look at us because they were still rare then. When I started graduate school, I drove up to Harvard in that car.

I got interested in a field called electrogenerated chemiluminescence, where you could take electrochemistry and generate light. That was really interesting, really beautiful and really fun. Then I thought, why take electricity through chemistry to make light – we do it anyway and this isn’t that efficient. It’s much more interesting to take light and make electricity and do chemistry. That’s what got me into photoelectrochemistry, and was the start of my interest in artificial photosynthesis.

The chairman of the chemistry department at the University of Texas, Norman Hackerman, called me up and offered me a job. I was of course happy that I got a job, but I said, ‘I’ve never been to Texas in my life. Don’t you want me to come down and give a lecture or something?’ He said no. I think he didn’t want to pay the fare, this was rather early in the flying game. I also think he was a little nervous about me seeing what the labs were like compared to Harvard.

I’m very proud of my students and how well they’ve done

What I really couldn’t stand was the segregation. I hadn’t even thought about it – I didn’t think about Texas as part of the South, I thought of it as a western state. The university had just integrated a couple of years earlier, in terms of taking some African American students, but bathrooms were segregated on campus, water fountains … Black students couldn’t go to movies, they couldn’t go to restaurants. I went to see Hackerman and said, ‘I really can’t stay. It’s just not my character to do this and never has been.’ He said, ‘You’re right. But if you go, you’ll do nothing to help. If you stay, maybe you can help change things, because things are changing.’

We had two African American graduate students in the chemistry department, who I was very friendly with. I’d asked how they were getting paid, and they said, ‘We have to get money from wherever we can, because they won’t let us be teaching assistants.’ I said that’s ridiculous, and so that was my big campaign at the university – I tried to pass around petitions that Black students should be allowed to teach and get paid as teaching assistants. It took a couple of years, but they came around.

Your students are the most important thing. Training and teaching them a kind of philosophy of research and of ethics, and watching them go on to good careers. For most of us, you have to be realistic – we make our contribution in terms of the science, and then it’s forgotten who did it. But your students go on and they have students and those students have students, and they all make big contributions. I’m very proud of the students I’ve had and how well they’ve done.

I think for a variety of reasons, science has lost the respect in society that it had in earlier years. To me that is a big threat – that the general public is much less convinced that science tells the truth. That’s especially true in the United States now, because we have [President Trump] who doesn’t know and doesn’t understand and doesn’t believe it. I think that’s a problem. You have to convince the public of real scientific ethics and the idea that science tells the truth as best it can.

This article was updated on 14 February 2024 to clarify the identity of the sitting US president at the time of the interview

No comments yet