Briony Marshall’s sculptures find form in her biochemical background, she tells Manisha Lalloo

When she was five years old, Briony Marshall decided she was going to be an artist. Three decades later, Marshall is a sculptor based in London, UK. But although she has achieved her ambition, the journey hasn’t been straightforward, and the figures that now fill her works show traces of her former life.

Despite her love of art, when Marshall left school she decided to study science at the University of Oxford. ‘I was good at science,’ says Marshall, ‘so I was encouraged to do an academic degree rather than an art degree.’ Marshall chose biochemistry, which she felt was an up-and-coming area: ‘It seemed to be one of the most exciting sciences where real developments were being made.’

Marshall’s four years at Oxford were spent balancing a hectic extracurricular life – in her first year she became editor of the student newspaper – with her scientific studies. In 1997 she graduated with a degree in biochemistry and, with many of her friends already working in London, took up a job for a growing internet company in the city. However, Marshall’s passion for art never faded and, after four years of working as a project consultant, she decided to embark on a more creative career route. In November 2004 she enrolled at an independent art school where she began a second degree, this time in art, specialising in sculpture.

Scientists are far more likely to talk about beauty than artists

Initially, Marshall turned her back on science, but as her artistic work progressed she began to use the scientific mindset she had developed at Oxford as a prism through which to view and develop her work. ‘I kept getting interested in how you could use things that happen at the microscopic level as metaphors for a better understanding of what happens in society and to us as humans,’ she says.

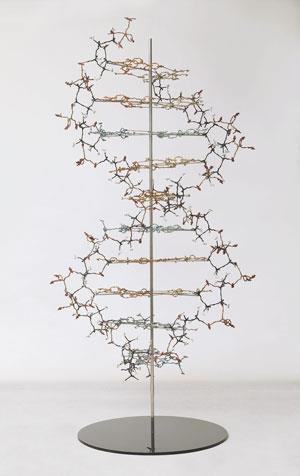

In a recent piece, DNA: helix of life, currently on display at Kings Place in London, Marshall uses sculpted human figures to replace the ball and stick models chemists so often use to depict molecules. ‘The big thing is this idea of macro–micro parallels,’ says Marshall. ‘The way that atoms interact with each other can be used as models for the way that people behave.’ For example, instead of a red oxygen atom, a crouching woman reaches up to hold a male figure with outstretched arms – their embrace representing a C=O bond.

Marshall first explored this idea in her piece The secret lives of the oxygen atom. She used sculpture to show that, as in our own lives, the oxygen atom can take on different roles depending on what it is interacting with. As a diatomic gas, Marshall’s anthropomorphised oxygen is comforting a twin sister, whereas in water, oxygen becomes a mother to two tiny hydrogen babies. At the time, Marshall was thinking of her own sister, who occupied very different roles of doctor, mother and friend. ‘They seem like very different identities but you always have these inherent ways of behaving, further influenced by the environment.’

Forging a career in art is not easy, and in her early years Marshall juggled part time jobs alongside her art work. However, with the support and encouragement of her family she was able to take up a succession of artist residencies both abroad and in the UK.

Today, Marshall is relocating her studio to a purpose-built building in her back garden, and is exploring the idea of creating a new series of works around the theme of water. Although Marshall usually carries out research on scientific areas for her sculptures herself, for this new piece of work she is considering working in collaboration with a scientist. ‘It’s funny, because scientists are far more likely to talk about beauty than contemporary artists,’ she adds.

As a sculptor Marshall finds that she can to take a wider view on science than she would be able to in a lab. ‘The reason I never wanted to be a biochemist was because I was a bit too impatient,’ she says. ‘For the early days of your career, unless you’re really lucky, you’re studying a tiny bit of the jigsaw and you don’t get to see the bigger picture – but that’s the bit I like best.’

Read more from our chemistry and art theme issue

No comments yet