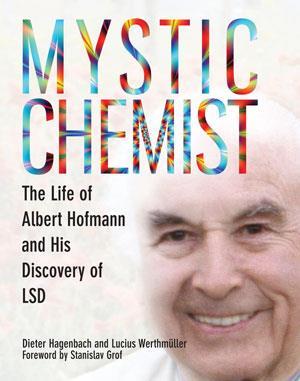

Dieter Hagenbach and Lucius Werthmüller

Synergetic Press

2013| 382pp | £34

ISBN 9780907791447

On the eve of the second world war, two Swiss chemists, working for different companies, made compounds that were to have a major impact on the world and divide society. Paul Müller made dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) at Geigy in September 1939 and went on to win the Nobel prize for medicine in 1948. And Albert Hofmann made lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) at Sandoz in November 1938, but never won the Nobel prize, mainly because LSD had become very controversial by the 1960s. DDT did as well, but for different reasons.

Hofmann joined Sandoz in 1929, where he worked on the chemistry of squill plants and then on the derivatives of lysergic acid, the basis of the ergot alkaloids. In 1938 he had the idea of making the lysergic acid analogue of the successful cardiovascular stimulant nikethamide (nicotinic acid diethylamine), but lysergic acid diethylamide seemed not to be medically useful.

Oddly, apparently no one noticed LSD’s hallucinogenic properties at the time. However, five years later Hofmann decided, for no rational reason, that he wanted to examine LSD again. This time, he accidentally experienced its mind-altering properties and thus began a series of experiments on its effects. Remarkably, at least with hindsight, Sandoz made LSD available to the medical community for research purposes, under the trade name Delysid, until 1966 when Sandoz agreed to withdraw it from circulation under pressure from the US government.

Rather than distancing himself from his ‘problem child’, Hofmann was enthusiastic about the use of LSD by physicians, but recognised that it had been misused by the counter-culture of the late 1960s. His work brought him in touch with a wide group of people interested in hallucinogenics. For example, he met counter-culture personality Timothy Leary for the first time in Switzerland, when the psychologist was on the run from the US authorities. After he retired, Hofmann wrote about the philosophy of life, and became something of a cult figure himself.

The authors of Mystic chemist are neither chemists nor historians of chemistry, and while the book covers Hofmann’s chemical research reasonably well, it is not the focus. Nor do we learn anything about Hofmann’s contacts in the wider world of chemistry. Perhaps working for a company he did not have any, although it seems surprising that he never crossed paths with Carl Djerassi given their mutual interest in psilocybin. There is some interesting material about his relations with the management of Sandoz, including its refusal to pay him the salary he demanded in 1967, which greatly pained him. The company eventually made up for this by increasing his pension years later. The book is beautifully produced and the numerous pictures, many in full colour, are excellent.

Purchase Mystic chemist from Amazon.co.uk

No comments yet