Europe's Joint Research Centre has played a significant role in developing Reach legislation and is at the forefront of the drive to develop alternatives to animal testing.

Europe’s Joint Research Centre has played a significant role in developing Reach legislation and is at the forefront of the drive to develop alternatives to animal testing.

As the EU’s Reach (registration, evaluation and authorisation of chemicals) becomes a reality, with implementation scheduled for next year, the heat is on to find ways to deal with the legislation’s practical issues. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) is playing a key role in this and has guided Reach from the very start.

Assessing the risks that chemicals pose to humans under Reach could cause a dramatic increase in the number of EU animal tests. This has not gone unnoticed by EU policy makers and there is a great drive to develop alternatives to animal testing.

The JRC, which is spread across Europe, is heavily involved in this process. Its European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (Ecvam) was set up in 1991 in Ispra, Italy, to evaluate possible alternatives to animal testing and promote their availability.

European animal welfare legislation already dictates that a reasonable alternative to an animal experiment must be used whenever it exists. However, it is extremely difficult for regulators to judge whether a novel alternative method is indeed suitable to replace standard tests, says Thomas Hartung, head of Ecvam.

To date, 23 alternative methods have been validated formally and around 40 are currently under study. These methods span areas from chemical safety (acute lethality, sensitisation, skin corrosion, phototoxicity, haematotoxicity, embryotoxicity, and ecotoxicity) to drug safety (pyrogenicity) and quality control (vaccine production control).

Ecvam follows the standard 3R approach - reduce, refine and replace. Under reduce, scientists attempt to obtain the same scientific information with fewer animals. This can be achieved, for example, with reduced group sizes or tiered testing strategies, where small groups of animals are tested in sequence, with the dose applied dependent on the outcome of the previous step. This technique has reduced the number of animals used for acute lethality per substance from 45 to eight. In March 2006, Ecvam validated a similar test strategy, which reduces fish use for ecotoxicity testing by 60 per cent.

Under refine, the aim is to reduce animal suffering, for example by using non-lethal endpoints or analgesics and anaesthesia. A prominent example is the local lymph node assay for skin sensitisation, which is currently a worldwide standard. This monitors lymph node swelling in a small number of mice and replaces earlier tests in guinea pigs which measured a chemical’s allergising potential by inducing a skin reaction.

The ultimate goal remains to replace animal tests. In vitro cell cultures are widely used and computer modelling also offers great possibilities, but no programme has yet been validated, says Hartung.

’With regard to animal numbers, the field of drugs is much more important than the area of chemicals,’ says Hartung. ’Industrial chemicals only account for about 150,000 animals per year in Europe, compared with some million animals required for Reach, while vaccine production control alone consumes 1.6 million every year.

’An alternative method for testing drugs for bacterial contamination for example has reduced animal tests from about one million to 200,000 and five novel tests validated by Ecvam in March 2006 promise to finally substitute for this animal test.’

Animal consumption through testing in Europe has dropped by about 50 per cent over the past three decades, says Hartung, thanks mainly to alternative ways to identify new agents. Safety toxicology, especially regulatory toxicology, is an exception, where many animal tests have changed little over decades.

These animal tests have also never been formally validated - at least not according to current standards. According to Hartung, many animal experiments are not carried out because they are too costly and laborious; for example the cost per substance for a cancer bioassay is around €800,000 (?547,000), reproductive toxicity €400,000 and neurodevelopmental toxicology €1.1 million.

From about 4000 new chemicals notified in Europe within the past 25 years, only 14 have been tested using the cancer bioassay, 70 in the two-generation test for reproductive toxicology and two for neurodevelopmental toxicology.

The impact of novel technologies on animal consumption can be substantial; several independent assessments predict 50 to 70 per cent possible reduction using alternative approaches in regulatory toxicology. In general, industry is very favourable to alternative methods, which are usually less costly, allow higher throughput and create fewer concerns for the public.

Nanotoxicity

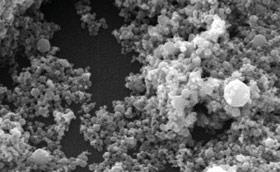

One of the issues raised in Reach discussions is how nanoparticles will fit into the legislation. The JRC’s nanobiotechnology unit works in a support role to Ecvam and the JRC’s European Chemical Bureau (JRC-ECB), providing technical and scientific knowledge to their programmes, including Reach. ’We work on different protocols to assess toxicity in nanotechnology, developing testing systems to measure the toxicity of nanoparticles,’ says Francois Rossi, action leader in the unit. ’We also design sensor systems to detect toxins in food, air water or even organisms.’

Rossi predicts that most industries will benefit from developments in nanotechnology. The unit works on nanobiotechnology in the field of health, with applications in drug development, health therapies and imaging (theranostics). ’Our background is in surface and interface sciences. We have also been working with biomaterials which are used as human implants, for example in orthodontics,’ says Rossi.

Register with Reach

Registering chemicals under Reach will be a complex and technical task. The JRC is the technical coordinator for creating the central chemical database called Iuclid5 (International uniform chemicals information database), which industry will use to help register chemicals under Reach. In June, the new software was tested by representatives from the future user community, with promising results. If all goes well, the JRC project team plans to roll out Iuclid5 to over 3000 companies and EU member state authorities from December 2006.

The JRC is also responsible for the analysis and design phase of the Reach-IT tool, which incorporates Iuclid5. This will be used by the European Chemical Agency, which will be based in Helsinki, Finland, to provide industry with a portal for submitting data and will make non-confidential information on chemicals freely available. ’We work very closely with industry, the member states and the commission on this,’ says Steven Eisenreich, head of the JRC-ECB. ’It is one of the few examples where such a trilateral relationship has worked well. Big and small industry has delivered the message to us about the help they need.’

Food issues

The JRC also plays a significant role in controlling genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the food chain. The European Network of GMO Laboratories (ENGL), which is chaired and managed by the JRC, is a platform of EU experts that plays an important role in developing and standardising means and methods for sampling, detection, identification and quantification of GMOs or derived products in a wide variety of matrices, covering seeds, grains, food, feed and environmental samples.

The network was formed in 2002 and consists of 74 national enforcement laboratories, representing all 25 EU member states and Norway. Meetings are open to approved observers, including representatives from acceding and candidate countries.

ENGL is also responsible for the Community Reference Laboratory for GM Food and Feed, which validates analytical methods for GMOs under marketing approval. ENGL technicians check GMO product assessments and report to the European Food Safety Authority, which then decides whether a product can be released.

The JRC also works closely with GMO developers to help ensure that assessments are carried out efficiently, says Guy Van den Eede, head of the JRC’s biotechnology and GMO unit. ’We have bilateral meetings with the big producers, for example Monsanto, BASF and Syngenta, and with EuropaBio [the European association for bioindustries] to clarify procedures. This is a constructive and positive interaction which can lead to simplification of the process.’

The unit works predominantly with seed crops - for example maize (which accounts for around 60-70 per cent of cases) and oilseed rape, but also with cotton, potatoes, soya beans and rice. Validation is time-consuming, with around six months taken for each GMO. So far 13 GMOs have been cleared and a further 40 are in the process of validation.

Chemical challenges

The future holds some interesting challenges for the JRC and the centre faces some restructuring when the new European Chemical Agency is up and running.

The JRC-ECB was instrumental in drafting Reach. ’JRC-ECB in particular provided advice based on its long experience with the implementation of the current legislation,’ says Eisenreich, ECB head. Now that Reach is almost finalised and the European Chemical Agency is a reality, the JRC-ECB’s focus will inevitably change. Many, but not all, JRC-ECB tasks will move to the new agency. The JRC-ECB will continue to exist but is likely to be renamed the Toxicology and Chemical Substances unit.

More important, says Eisenreich, is that the JRC-ECB, as part of the commission, will continue to provide support to the policy directorate generals on matters relating to the human and environmental health and safety of chemicals. Moreover, he predicts that the European Chemicals Agency will request scientific advice and support in completing its legislative tasks. This may include the further development of technical guidance on different aspects of the chemical legislation, for example risk assessment, developing computational techniques to estimate dangerous properties of chemical substances, and information on exposure to substances.

The JRC’s work is indeed varied. The entry into force of Reach in 2007 will ensure that its units with complementary interests in chemicals and chemistry work together to ensure the efficient introduction and operation of the new legislation.

Mark Whitfield is a freelance journalist

JRC facts

- The Joint Research Centre (JRC) works in parallel with industry in many areas to ensure the efficient adherence to legislation and regulation, but is independent of private or national interests.

- The centre was established in 1957 with the Treaty of Rome and works to ’improve understanding of the links between technology, the economy and society’. Its activities range from coordinating Europe’s first soil atlas to identifying alternatives to animal experiments.

- The JRC has 2650 employees and operates in Italy, Belgium, Spain, Germany and the Netherlands. It is organised in seven scientific institutes and currently has an annual budget of €300million (?200million).

- The JRC provides direct support for EU policy makers through its directorate general (DG) located in Brussels, Belgium. The centre’s European Chemicals Bureau provided technical support and advice to the policy DGs - DG Environment and DG Enterprise - during the drafting and negotiation process of Reach (registration, evaluation and authorisation of chemicals), as well as to the European Parliament prior to the first reading of the Reach proposal.

- The JRC is also responsible for developing and finalising the Reach implementation projects for preparing technical guidance documents for industry, member states and the new European Chemical Agency, which is being set up in Helsinki, Finland.

No comments yet