British celebrities have joined forces to help raise £100 million for research into photodynamic therapy (PDT).

British celebrities have joined forces to help raise ?100 million for research into photodynamic therapy (PDT), a cancer treatment they say offers unprecedented, but unrecognised, potential.

Passions ran high as the charity Killing Cancer was launched at University College London on 6 July to raise awareness of the therapy.

’How come PDT is relatively unknown in the medical world, especially among GPs, when the National Medical Laser Centre [NMLC] at UCL has been successfully treating cancers with PDT for years?’ thundered Killing Cancer’s evangelical director, David Longman.

Nobody mentioned PDT’s well-publicised worst ever day in 2000 when drug company Scotia QuantaNova collapsed following refusal by both the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products to grant licences for a PDT drug called Foscan. Faults in the company’s trials procedures were blamed.

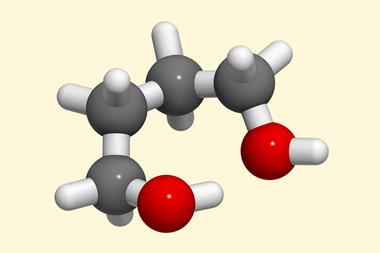

Steve Bown, director of the NMLC, told delegates at the launch how PDT works. ’Patients receive a light-sensitive drug that is given time to equilibrate in the body,’ said Bown. ’Some drug localises in tumours, which then fluoresces red when irradiated with non-thermal, red laser light. This same gentle light is used to kill the tumour. The photosensitising drug becomes excited by the light and that excitation is passed on to oxygen close by.’

The reaction produces a kind of super-active ’bleach’ that for a short time kills anything in its path, in this case the dyed tumour cells that produced it in the first place, says Bown.

Facio-maxilliary surgeon Colin Hopper, a veteran of over 500 PDT procedures, was also present at the launch. Hopper is trained to wield a scalpel in one of the most crowded areas of the human body, but says that PDT has reduced his role to switching a light on and off.

’The treatment is minimally invasive, requires no major surgery and can be repeated as often as needed,’ said Hopper. ’A range of cancerous tissues in hollow and dense organs are treatable with PDT - including skin, lung, colon, bladder, cervical, pancreas, and prostate - and it can be used in conjunction with other conventional cancer treatments.’

But there are drawbacks, he cautioned. ’Tumours need to be localised - metastases are difficult to treat - and the drug appears all over the body making patients highly photosensitive to daylight, sometimes for up to six weeks after treatment. However, most patients consider this a small price to pay for complete and cosmetic removal of cancerous growths.’

PDT does not damage the underlying scaffolding of elastin and collagen that supports tissues and organs in the body, added Bown, so healing occurs with little or no scarring.

’Killing Cancer needs to raise ?100 million to further this research,’ said the charity’s director, Longman, ’But we also need to get PDT’s message of hope across to the media, politicians, and most of all, the public.’

TV and radio personality Chris Tarrant, who presents the TV series Who wants to be a millionaire?, echoed Longman’s enthusiasm. ’Surely we should increase further investment in R&D for PDT,’ he told delegates. ’We owe it to ourselves and our kids to try and make that possible.’ Lionel Milgrom

No comments yet