China's artemisinin producers face market collapse

Hepeng Jia/ Beijing, China

Just three years ago, a global shortage of the antimalarial natural product artemisinin alarmed medics fighting the killer disease, and spurred scientists who were developing alternative sources of the drug.

Yet a glut of the compound has now saturated the market to such a degree that prices have slumped, threatening to put some Chinese drug manufacturers out of business.

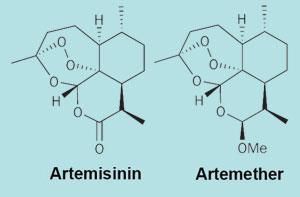

Artemisinin is derived from the sweet wormwood plant Artemisia annua, and China is home to 80-90 per cent of the world’s supply. Much of that is bought by Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis for its antimalarial treatment Coartem, an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) which contains both artemether (see box) and lumefantrine.

The need for Coartem is overwhelming. There are between 300 million and 500 million new cases of malaria each year, causing more than one million deaths annually. Children in Africa account for 90 per cent of the fatalities. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Novartis provided 62 million doses of Coartem to Africa in 2006, at a lower-than-cost price of $1 per dose. This effort has been overseen by the WHO since 2001, and funded by grants from, among others, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

But the sudden increase in demand for artemisinin caused a serious shortage of qinghao, as sweet wormwood is known in China. This triggered a massive artemisinin price rise that peaked at 8000 yuan (?537) per kilogram in 2005. To capitalise on this, the number of Chinese artemisinin producers rose from three in 2004 to more than 80 in 2007, and qinghao plantation area more than doubled to about 70,000 hectares in 2006.

Rapid growth

China’s annual supply of artemisinin now stands at about 150 tonnes per year. Yet in July 2007, Novartis announced that it would buy just 50.5 tonnes of artemisinin over the following two-year period. Although this was in line with Novartis’ average annual purchase of artemisinin in previous years, Chinese manufacturers had expected a significant growth in consumption. The resulting surplus has caused the market price of artemisinin to plummet to around 1600 yuan per kilogram. As most artemisinin producers are small businesses, local media report that the crash has already forced some to halt production.

On 20 October 2007, industry representatives and government officials met at a meeting organised by the quasi-governmental Beijing Pharma and Biotech Center to discuss the problem. Reports of the meeting, which became available in late November, say that when Chinese participants tried to persuade Novartis to buy more artemisinin, the company refused. Meanwhile, Ministry of Commerce officials at the meeting suggested that the government could control the oversupply by introducing new rules to control exports.

Novartis argues it is not responsible for the business crisis. ’We have repeatedly warned Chinese suppliers that the African anti-malaria market is very small due to their low consumption capacity,’ explained a spokesperson for Novartis China. ’The purchase of ACT by international charity foundations cannot be enough [to support their current production capacity].’

They added that the WHO is unlikely to buy more artemisinin without an increase in their funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Overheated market

Qinghao had been used in traditional Chinese medicine for millennia before Chinese scientists first extracted artemisinin in the 1970s. Yet only one Chinese firm - Guangxi-based Guilin Pharmaceutical - has obtained WHO approval to sell its ACT, a mixture of artesunate and amodiaquine. Since that approval was granted in August 2007, the company says its export of artemisinin products has seen robust growth. ’But the artemisinin used for our ACT comes from our own plantation, and it can do little for the market glut right now,’ a Guilin Pharmaceutical official said.

Besides Novartis and Guilin, three other firms - Sanofi-aventis in France, Artecef in the Netherlands, and Ipca in India - currently have WHO approval to supply artemisinin-based antimalarials.

Other Chinese companies in the industry tend to produce artemisinin as a raw material. The artemether that goes into Coartem is produced for Novartis by the Kunming Pharmaceutical Corporation of Yunnan province, for example.

But Kunming has also been rapped by the WHO for selling an artemisinin-based monotherapy, Acro. The agency insists on using combination therapies - since the constituent compounds work differently, they can delay the development of drug resistance in the malaria parasite. Kunming argues that it is providing a valuable treatment that makes use of the artemisinin surplus.

Great hope

So why has the artemisinin industry found itself in this situation? ’Our pharmaceutical industry is too eager to sell their products abroad without carefully studying the market,’ said Liu Zhanglin, director for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) department at China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Medicines and Health Products.

Zhou Chengming, president of Beijing-based Shizhen TCM Group, suggested that the Chinese drug regulator - namely the State Food and Drug Administration - has issued licenses to produce artemisinin too easily, and has been ineffective in trying to close down unauthorised producers. ’Local governments should be blamed as well,’ he added. ’They have exaggerated artemisinin as the great hope for Chinese pharmaceuticals to go abroad.’

No comments yet