Using the natural properties of gold nanoparticles could lead to a sensitive test for cancer

Gold nanoparticles could help diagnose a wide range of different cancers by detecting telomerase activity within cells, say Chinese chemists.

Telomerase is an enzyme that extends the ends of chromosomes, known as telomeres, by adding a short sequence of DNA bases to them. Telomeres help to ensure that all the DNA within a chromosome is replicated during cell division, but they tend to get used up in the process. Once a cell’s telomeres are all used up, then it can no longer replicate, unless telomerase is available to extend the telomeres.

Usually only certain cells in the human body produce telomerase, and so most cells are unable to reproduce indefinitely. Unfortunately, when a cell becomes cancerous telomerase gets switched on and the cell starts to reproduce out of control.

Because telomerase is over-expressed in over 85 per cent of all tumours, it would make a good, general biomarker for cancer but although techniques exist for detecting telomerase levels they suffer from some serious limitations, including being time-consuming, expensive, and not particularly accurate or sensitive.

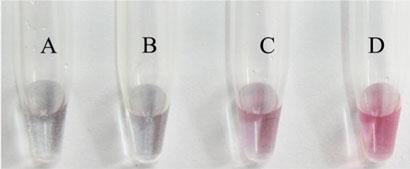

Chemists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry, led by Xiaogang Qu, decided take advantage of the fact that gold nanoparticles are naturally fluorescent and change colour depending on whether they are dispersed in a solution or bunched up together. Bunching depends on salt concentration, which stimulates bunching, and whether the nanoparticles are coated in any molecules, which can prevent bunching.

Qu and his team coated their gold nanoparticles in a synthetic version of a telomere that could be extended by telomerase. Placing these gold nanoparticles in a salt solution caused them to bunch together, shifting their fluorescence from red to blue. If, however, the gold nanoparticles were first exposed to telomerase, then the extended telomere molecules prevented the nanoparticles from bunching up and they continued to shine red.

When the gold nanoparticles were exposed to the telomerase produced by just 10 cancer cells, this blue fluorescence could be seen with the naked eye. With UV spectrometry, however, Qu and his team found that they could detect blue fluorescence caused by the telomerase of a single cancer cell, making this technique far more sensitive than any previous version. It’s also much faster: taking 10 minutes rather than several hours.

Qu and his team are now trying to make the technique even more sensitive: ’We are making efforts to lower the detection limit of the method and modulate the detection range,’ Qu tells Chemistry World.

Jon Evans

References

J. Wang, Li Wu, J. Ren and X. Qu, Small, 2011 (DOI: 10.1002/smll.201101938).

No comments yet