Researchers have measured the rise and fall of chemicals in their own bodies after using everyday products

Scientists have often experimented on themselves to prove a point. Now two Canadian environmentalists have detailed the rise and fall of chemicals in their own bodily fluids after using everyday products. And they were shocked by the results.

Bruce Lourie is president and chair and Rick Smith is executive director of Canadian environmental organisation Environmental Defence. In their book Slow death by rubber duck, the pair detail a weekend testing spree incorporating regular blood and urine sampling. Indoors for 12-hour shifts, they used typical amounts of personal care products and a plug-in air freshener, in a room with stain-repellent furnishings and carpets. ’We set only one ironclad rule: our efforts had to mimic real life,’ says Smith.

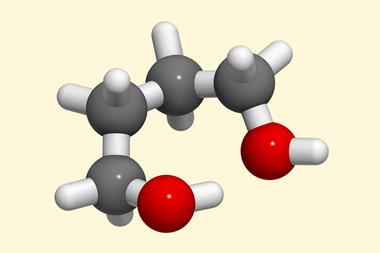

Of six different phthalates in the testing regime, rocketing levels of monoethyl phthalate (MEP) - which the body metabolises from diethyl phthalate (DEP) the most common phthalate in cosmetics and personal care products - were most stark. Levels in urine went from 64 to 1410ng/ml. According to the European Commission’s Scientific Committee for Cosmetic Products (SCCP), traces of up to 100 ppm total or per substance pose no risk to health, although traces of banned phthalates are sometimes present due to other possible uses, such as in packaging. Phthalates are plasticising chemicals, linked to abnormal reproductive development.

Eating just three meals containing tuna more than doubled Lourie’s blood mercury levels to 7.55?g/L in less than 48 hours. The US Environmental Protection Agency reference dose level for the neurotoxin is 5.8?g/L, which if exceeded is cause for concern. Levels of bisphenol A - an endocrine disruptor linked to breast and prostate cancer - increased 7.5 times after eating canned foods from a microwavable, polycarbonate plastic container.

Triclosan (an antibacterial found in toothpaste, soap and deodorant) levels in Smith’s urine jumped from 2.47ng/ml to 7180ng/ml after exposure - increasing 2900 times. Smith usually avoids antibacterial products, so his baseline level was low compared to the average North American (mean 13ng/mL). Triclosan bioaccumulates and has been found in infant cord blood and breast milk. Studies suggest it is an endocrine disruptor and affects thyroid function, and there is ongoing debate about its role in bacterial resistance. The SCCP states that Triclosan is safe.

Smith avoided everyday products containing Triclosan, phthalates and bisphenol A for 48 hours before the experiment, and Lourie ate no fish for a month. Testing protocols were suggested by Harvard School of Public Health phthalate expert, Susan Duty.

High levels of chemicals in urine mean the body is doing a good job of excreting them, rather than telling us what remains in the body. But that is not really the issue, Smith told Chemistry World: ’All the chemicals we tested have been linked to serious human health problems. All have easy replacements. Any proper regulatory system would aim to eliminate them from the human body completely.’

The experiment is unusual in that it ’represents a snapshot of the exposure they are getting from these products,’ according to Professor Stelvio Bandiera, an expert on environmental chemicals and health at the University of British Columbia faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences. Typical studies look for population trends, and assume chemical levels in test subjects are at equilibrium. The authors’ experiment showed that the products contained chemicals and that these entered their bodies - previous experiments have not considered how quickly the levels rise.

Bandiera suggests that the snapshot approach is useful for raising awareness: ’Certain products do contain these chemicals. The public is poorly informed about the kinds of chemicals they are exposed to on a regular basis in food and consumer products.’

The levels in these products are safe according to Canadian and US authorities, and Bandiera says that there’s no immediate health concern. However, for babies and young children he adds a caution: ’We don’t want them to be exposed unduly to chemicals that they are unable to metabolise, and will stay with them for a long time.’

The authors accept that their results are illustrative, but demonstrate that careful choices dramatically affect levels of ’personal pollution’. Bandiera agrees that ’you can make a conscious choice - you may not be able to avoid [specific chemicals] completely but you can reduce your exposure.’

’Testing of individuals for measurable amounts of pollution has become commonplace, though our demonstration of increases and decreases in pollution levels is brand new,’ Smith says.

Helen Carmichael

References

Slow Death by Rubber Duck, Knopf Canada (Random House), 2009. ISBN 987-0-307-39712-6

No comments yet