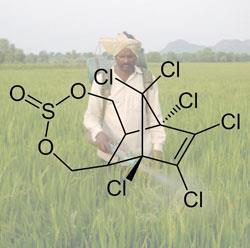

A global ban on the pesticide endosulfan has been introduced after initial resistance from the Indian government was overcome

Ned Stafford/Hamburg, Germany

India has reversed its opposition to a ban on the pesticide endosulfan, paving the way for the 127 nations of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) to agree a global moratorium on the use of the highly toxic pesticide. As the world’s largest producer of the chemical, including state run production facilities, India has the most to lose from the ban.

China has worked with India in the past to oppose a ban, but reversed its opposition before the beginning of the Fifth Meeting of the Stockholm Convention held in Geneva, Switzerland, on 25 April. ’India wasn’t prepared to change its position when it went [to Geneva],’ according to Savvy Soumya Misra, assistant coordinator for food safety and toxins at the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi, which has for years campaigned against endosulfan. Misra says that the Indian government did try to float a draft statement on behalf of the Asia-Pacific countries maintaining that endosulfan was safe, but it was unsuccessful.

Agreement was reached on the final day of the conference on a ban, which will take effect next year, making endosulfan the 22nd POP to be listed by the convention. ’India had to concede or it would have been the only country opposing the ban,’ Misra says.

In order to gain India’s agreement, the Stockholm Convention exempted 14 crops for a five-year phase out period, during which India will receive financial assistance to help with the switch to alternatives. Additionally, India has the option to apply to the Stockholm Convention for a second five-year extension.

India’s government must ratify the agreement before the phase out can start. The country is home to nearly three-quarters of global production of endosulfan, which is off-patent and, therefore, much cheaper than newer patented pesticides. Endosulfan has already been banned or is being phased out in most countries, including the EU and the US. In addition to Indian companies, the Israeli company Makhteshim Agan is the only other producer of endosulfan.

Utz Klages, spokesman for Germany’s Bayer CropScience, told Chemistry World that the company ’stopped manufacturing of products containing endosulfan in 2007 and discontinued sales of these products worldwide. New active ingredients with markedly better risk profiles are available to our customers.’ He added: ’Bayer CropScience welcomes the decision of the Stockholm Convention in Geneva for the elimination of production and use of endosulfan and its isomers worldwide.’

In the Indian state of Kerala, the deaths of hundreds of people and the illnesses of thousands of others have been linked to endosulfan. However, Indian endosulfan producers, the Indian Chemical Council and farmers groups have insisted that the problems were caused by illegal aerial spraying in the late 1970s. They contend that there is no conclusive scientific evidence linking human health problems or environmental damage to endosulfan - when it is used properly.

Misra counters: ’There are many reports to suggest that the chemical is hazardous to human health and the environment. The Indian Chemical Council is a body of the pesticide companies and ever since they realised that there was a threat from the Convention of a potential ban of endosulfan, they started a campaign against studies that indicted endosulfan.’

The Indian Chemical Council did not respond to requests from Chemistry World for comment.

In the Indian press, opponents of the decision alleged that European companies lobbied for the ban so as to improve market share of their pesticides, which are still under patent.

’The problem is whenever there is some talk of alternatives, the pesticide lobby can only think of replacing it with chemical alternatives 10 times costlier than endosulfan,’ Misra says. ’But there are non-chemical alternatives and they have been very successful. Moreover, it is the responsibility of the government to stop thinking in terms of money, but in terms of the health of farmers and if it has to go with chemicals then it should manufacture safer and cheaper products.’

No comments yet