Campaign group says Gilead’s expensive blockbuster sofosbuvir is not innovative enough to warrant a patent

A French healthcare campaign group has launched a legal challenge to the patent covering Sovaldi (sofosbuvir), the blockbuster hepatitis C virus (HCV) drug marketed by Gilead. Médecins du Monde (MDM) has told the European Patent Office (EPO) ‘the molecule itself is not sufficiently innovative to warrant a patent’.

HCV infection can clear within a few months. But for about 80% of those infected, it develops into a chronic condition. According to the World Health Organization, 130–150 million people are living with chronic HCV infection.

Sofosbuvir was hailed as a major breakthrough in HCV treatment. Gilead gained access to it in 2011 through its $11 billion (£7.1 billion) acquisition of Pharmasset. In the year after its launch – in December 2013 in the US and in January 2014 in the EU – the drug generated over $10 billion in sales, making it one of the most commercially successful drugs ever.

But patient groups have complained about the cost. MDM says that a 12 week course of treatment costs €41,000 (£30,200) in France or £35,000 in the UK, and these ‘unconscionable’ prices have forced them to act against the patent.

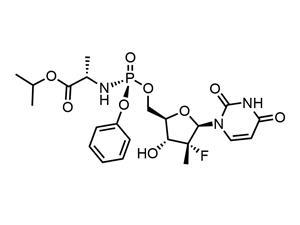

The molecule is composed of two parts: a nucleoside analogue and a phosphoramidate. In its complaint, MDM describes Gilead’s the patent as ‘merely a list of thousands of compounds, of unknown activity for the most part, clearly aimed at reserving an unexplored field of research instead of protecting factual results of successful research as a reward for making concrete technical results available to the public’.

In addition, the molecule follows from ‘simply aggregating the contributions of various researchers from the scientific community’.

‘Patent oppositions like this are quite common, and it certainly isn’t unusual for them to be successful,’ says Emily Cottrill, a patent attorney and partner at London firm AA Thornton. But success is often a matter of degrees: an opposed patent might be fully maintained or revoked, or it might be maintained in a limited form. Regardless of the initial outcome, an appeals procedure is available, plus the opposing party can challenge again at the national level, but this tends to be much more expensive.

Cottrill says that the ‘inventive step’ patent requirement is often the most hotly contested. ‘Some requirements – such as the one relating to novelty – can prove quite black and white in practice. But inventiveness can seem more of a subjective analysis. What is starkly obvious to one person might be completely opaque to someone else. The EPO has a systematic approach to the issue, based on how a “skilled person” would view the invention, but even so it can be very difficult to predict which way they will go.’

The price of sofosbuvir is not relevant to the validity of the patent. But it raises familiar questions about the ability of health providers to pay for the most innovative drugs.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) has said that sofosbuvir is a cost-effective treatment for some patients. But in an unprecedented move, NHS England is delaying its scheduled implementation, seemingly on the basis of affordability. In its final draft guidance on sofosbuvir, Nice said it was allowing postponement for four months, until the end of July.

What might represent a fair price for treatment? Céline Grillon, advocacy officer at Médecins du Monde says that it is not for MDM to give numbers – drug pricing is a necessarily complex process that has to take into account many factors. But setting the price based on damage incurred by not using the drug is not appropriate. Additionally, the cost effectiveness argument is based on the assumption that the drug will only be given to the sickest patients – those requiring liver transplants. Many more people, who have chronic HCV infection but are not quite as sick, would also benefit. But for them, the current price is too high for healthcare providers to justify.

Michele Rest, director of public affairs at Gilead, told Chemistry World in an email that the company is reviewing the opposition. ‘It is disappointing that [MDM] appears to be disregarding the innovative nature of this important cure for hepatitis C. Gilead will continue to vigorously defend the science and intellectual property behind its hepatitis C medicines, while continuing efforts to enable patient access worldwide.’

No comments yet