From crabsticks to plastics as researchers find a new use for these crustaceans

Researchers in Japan have made a crab shell transparent. Then, using knowledge gained from this activity, they created a transparent nanocomposite sheet, incorporating powdered chitin from crab shells. The nanocomposite could have applications in devices that need a high light transmittance, such as flat panel displays.

Scientists have previously used cellulose from plants and chitin to strengthen materials, giving biologically-inspired nanocomposites. If natural nanofibres are dispersed widely enough in a transparent polymer matrix, they can strengthen the polymer and the resulting nanocomposite material will retain its transparency. Work on optically transparent polymers containing cellulose nanofibres shows they have a low axial thermal expansion coefficient, meaning their size does not vary with temperature, making them ideal for use in flexible flat panel displays and solar cells.

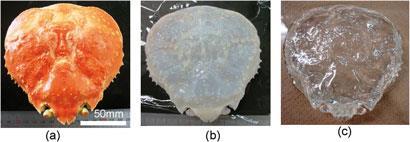

Muhammad Iftekhar Shams and co-workers from Kyoto University took a whole crab and treated it with hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide and ethanol to remove the minerals, proteins, fats and pigments, respectively. This gave a chitin-only crab shell, which they immersed in an acrylic resin monomer. Following polymerisation, they obtained an entirely transparent crab shell. The shell retained its shape and detail, right down to the creature’s eyes.

’Encouraged by the transparent crab, we undertook the development of optically transparent composites based on crab-shell chitin fragments in powder form,’ says Shams. This time, the team worked with crab shell powder, which was treated the same way as the shell to obtain micro to millimetre scale chitin powder particles. They made the particles into paper sheets and then impregnated them in the same acrylic monomer as before to give optically transparent nanocomposite sheets.

They measured the sheets’ light transmittance over a range of wavelengths and temperatures. Current composite technologies, such as glass-fibre epoxy composites, show decreases in transmittance of up to 65 per cent as the temperature is increased to 100?C. However, the chitin-powder composite shows virtually no decrease in light transmittance at temperatures of up to 80?C.

Tina Lekakou who studies structural systems at the University of Surrey, UK, believes the research could provide further insight into how natural materials such as chitin are composed. ’The preparation method gives a great opportunity to explore the exact structures of natural materials and incorporate them in synthetic nanocomposites,’ she says.

Mindy Dulai

References

M I Shams, M Nogi, L A Berglund and H Yano, Soft Matter DOI: 10.1039/<man>c1sm06785k</man>

No comments yet