Poor performance predicted for UK government.

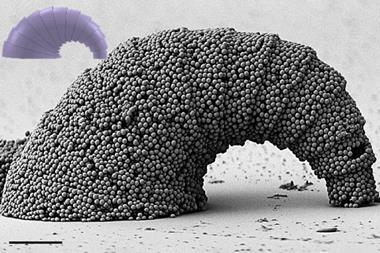

A review that will check whether the UK government has followed up on promises to regulate nanotechnology might struggle to find much progress, scientists predict.

The Council for Science and Technology (CST) will review what the government has done since responding to a 2004 report by the Royal Society (RS) and Royal Academy of Engineering (RAEng), which assessed both the opportunities and the hazards of nanotechnology.

The government agreed that there was a need for early regulation of nanotechnology products, but at the time came under fire for failing to provide extra funds to ensure any such regulation took place.

Action and funds - rather than another review - are still needed, said Anthony Seaton, an author of the RS’s 2004 report, and professor of environmental and occupational medicine at Aberdeen University.

’There hasn’t been a centralised effort [into nano-toxicology research] because there hasn’t been a specific direction of funds,’ Seaton told Chemistry World. He called for targeted DTI funds to support nanotechnology and specifically hazard and risk identification.

Another GM?

Sir John Beringer, who leads the CST review, said that the issue needs revisiting because new technologies have emerged since 2004 that might pose more of a threat to human health. Beringer chaired the government’s advisory committee on releases to the environment at the height of the fierce debate over genetically modified foods, and is aware ’how quickly things can go wrong’ when public sensitivity is pricked. ’I don’t think that nano is the same as GM - there isn’t quite the same emotional impact,’ he said.

Beringer’s committee reports directly to the prime minister, ’and I can assure you that if we do find serious omissions [in government action] we will be reporting on them,’ he said. He added that the CST review team will be looking to other countries for advice: government-funded researchers in Dresden, Germany, are already investigating the health risks of synthetic nanoparticles, for example.

’Clearly, it is useful to formally review what the UK government has done in the light of the 2004 report, but I think it will paint a disappointing picture,’ said Andrew Maynard, chief science advisor at the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, based at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC. ’What is more worrying is that we are seeing a trend of deferring action in the name of reviews - and in some cases, reviews of reviews.’

In contrast, Maynard’s group will publish a report next week that recommends not only a list of research needs for regulating nanotechnology, but also who should do the work and how much it will cost.

Blindingly obvious

The US government’s own National Nanotechnology Initiative, a body that spans 23 different federal agencies, is due to release the findings of a similar investigation this summer.

’But all reviews internationally have been pointing in the same direction,’ said Rob Aitken at the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM), Edinburgh. ’The views of what needs to be done are fairly inarguable.’

Aitken recommends that the UK government should consider ring-fencing a proportion of funds for risk assessment, something that has been promised by the US government but, according to Maynard, not delivered.

And while the UK’s regulatory framework for nanotechnology is progressing, ’there is a concern that we are going to be so good at providing a framework that we’ll miss sight of the real commercial opportunities’, said Otillia Saxl, who heads the Institute of Nanotechnology, Stirling, UK. ’I’d be disappointed if no key messages come out of this review,’ she said.

The CST committee is now calling for evidence. Written submissions will be accepted until 2 October 2006.

Katharine Sanderson

No comments yet