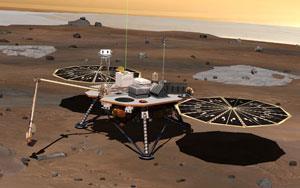

The Phoenix Mars Lander has carried out the first wet chemistry experiments on another planet

The Phoenix Mars Lander, which touched down on 25 May, has carried out the first wet chemistry experiments on another planet and found that Martian soil contains components important for life.

Although Phoenix is not a life detection mission, scientists have been studying the Martian environment for its potential to sustain life. Early results from Phoenix’s wet chemistry lab indicate that the soil on Mars is alkaline, with a pH of 8 or 9. According to Sam Kounaves, Phoenix’s wet chemistry investigation lead from Tufts University, Massachusetts, US, this is a level habitable by a range of microbes. His team has also found sodium, potassium, magnesium, chlorides and sulfates in soil sampled from trenches around the lander. Kounaves says that these components are, at least on Earth, important for life.

The wet chemistry lab onboard Phoenix was developed by Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in conjunction with Tufts University, US; lab equipment firm Thermo Fisher Scientific; and Starsys Research (now part of SpaceDev), a US space system company. The landerhas four miniature and identical labs for wet chemistry - each the size of a teacup. All four are housed inthe craft’s Microscopy, Electrochemistry and Conductivity Analyser (Meca). The labs will each analyse a different soil sample from Phoenix’s Arctic landing site, using ion selective electrodes similar to those used to measure electrolytes in blood. To date, the team has completed two experiments, using one surface sample and one subterranean sample taken from just above a sub-surface ice layer.

Soluble chemistry

The scientific data collected from Phoenix will take months to analyse fully. Until then we can’t know the true significance of the results, says Meca lead scientist Michael Hecht, from Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. For example, the team does not yet know the exact levels of the water-soluble salts found, although they lie somewhere in the hundreds or thousands parts-per-million range.

The Phoenix scientists have focused on soluble rather than elemental chemistry. Previous missions have collected strong evidence of water on Mars, including photographs of gullies and drainage valleys on the planet surface. By mixing samples of soil with water, scientists hope to reconstitute Mars’ watery past. ’If you’re a microbe or a riverbed you care about the soluble chemistry; you don’t care about the solid stuff that doesn’t affect you.’ explains Hecht.

Two out of three missions to Mars have ended in failure but Phoenix’s course so far has been smooth. However, the mission is not without difficulties. ’The general challenge is learning how to use the instruments in a new environment with completely unknown samples when they haven’t been turned on for a very long time,’ says Hecht. What may take a day in a laboratory may take a week on Mars, as fine-tuning the instruments requires results to be sent back and analysed before the next step can be taken.

While Meca hasn’t encountered problems, the same cannot be said for Phoenix’s ’nose’, the Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyser (Tega). Tega heats soil samples to study the components’ melting and boiling points using scanning calorimetry. Eventually the sample is heated to 1000?C and analysed by a mass spectrometer which detects organic molecules in the soil, along with their isotopic ratios.

The Tega team had trouble loading its first clumpy soil sample into one of the instrument’s six ink-cartridge sized cells. Although it managed to bake the sample to 1000?C, the cell developed a short circuit.

The Tega team is now being cautious and is treating its next sample, planned to be ice-rich, as its last. It will be weeks before a full analysis of the first sample is completed, but initial results indicate the presence of water vapour.

Back to Earth

While Phoenix’s results will be fascinating in themselves, they will also provide important groundwork for future Mars missions, says Andrew Coates, head of the planetary science group at University College London, UK.

The Phoenix scientists are conscious that Mars has a hugely diverse geology. ’We’re trying to make inferences about a whole planet from a teaspoonful of soil,’ says Hecht. ’We have to stay humble about what we can accomplish with one location on a far-away planet with relatively simple instruments.’

The ultimate goal, says Colin Pillinger, who led Britain’s unsuccessful Beagle II mission to Mars in 2003, would be to bring soil samples back to Earth. Instruments for landers have to be developed years in advance whereas, on Earth, scientists could use the latest techniques and obtain more comprehensive information.

Manisha Lalloo

No comments yet