The new technique relies on a twin approach of firstly identifying smaller protein building blocks that, according to computational predictions, should slot together to create a larger symmetrical structure. The second step involves modifying amino acids along the interface of where the building blocks meet to help them stick.

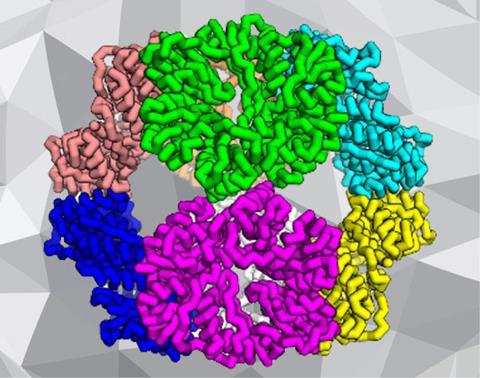

Neil King, of the University of Washington in Seattle, US, and colleagues successfully created two protein architectures in this way, a cube consisting of 24 separate building blocks, and a tetrahedron made from 12 sub-units.

The team asked the computer to place combinations of three peptide chains at the corners of a cube or a tetrahedron, and to see how snugly these trimers – eight for the cube and four for the tetrahedron – fitted together to make the final shape. For those that showed promise, the researchers analysed the amino acid sequences where the trimers met and suggested modifications to help increase the chances of a stronger interaction at this interface.

Hundreds of thousands of design trajectories were run on the computer based on 271 different protein building blocks. A total of 40 designs were then tested experimentally by synthesising the protein sequences through genetic engineering of a bacterium. The proteins were purified and mixed together. In two cases a resounding hit was scored, resulting in the self-assembly of one protein cube and one protein tetrahedron. ‘It's a fairly low success rate, which, while it is a testament to the difficulty of the problem, is something we're working hard to improve,’ King says.

King’s colleague David Baker says that the technique should be applicable to a wide range of proteins – both natural and synthetic – and opens the way to creating novel protein architectures for a wide range applications, such as drug delivery and vaccine design.

Meanwhile, at the University of California Los Angeles, Todd Yeates and colleagues have taken a slightly different tack to design and construct a protein cage in the shape of a tetrahedron.2 The team took two naturally occurring protein sub-units, a trimer and a dimer, which have an affinity for each other. They joined these together with a short molecular linker, which has the effect of orienting the two sub-units in a particular way. When many of these linked units are brought together, they spontaneously self-assembled into a tetrahedron.

Dek Woolfson, an expert in protein design at the University of Bristol in the UK, says: ‘This type of rational biomolecular design is important in advancing both protein and materials science and paves the way to new structures, functions and hopefully useful applications.’ The next challenges, Woolfson suggests, ‘will be to generate new building blocks from scratch – that is de novo – and to display functions within and on these frameworks.’

References

- NP King et al., Science, 2012, 336, 1171, DOI: 10.1126/science.1219364

- Y-T Lai et al., Science, 2012, 336, 1129, DOI: 10.1126/science.1219351

No comments yet