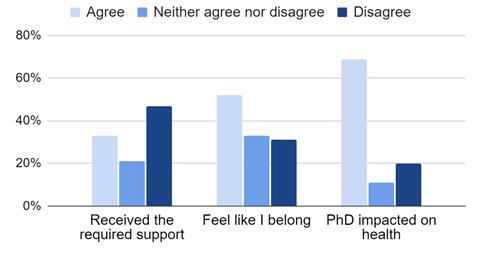

Only a third of Stem PhD students feel they receive sufficient support to be on an equal footing with their non-disabled peers according to a new report by Disabled Students UK (DSUK) and Pete Quinn Consulting.

The proportion of postgraduate research students (PGRs) with a declared disability has increased significantly over the last five years and this group now makes up 20% of the PGR community. But despite growing numbers of disabled students entering the research sphere, there has been little study into how institutions and funders can effectively support these individuals within the sector. Correspondingly, disabled postgraduates consistently rate their experiences more negatively than their non-disabled peers in student satisfaction surveys.

In collaboration with the Oxford Interdisciplinary Bioscience Doctoral Training Partnership, DSUK and Quinn evaluated the experiences of 192 doctoral students across England and Scotland to determine the key barriers to equal participation. ‘There are pretty good systems in place for undergraduate students and postgraduate taught students. But postgraduate research students have a particular requirement which often isn’t met by undergraduate student arrangements,’ says Quinn. ‘The assessment process is very much skewed towards a taught environment rather than a research one. Lecture support and examination adjustments don’t translate into PhD practice so students get very frustrated that recommendations just aren’t relevant.’

The team identified several other key challenges, with ambiguity and bureaucracy highlighted as two of the major barriers for students seeking support. Less than half the surveyed PhD students knew where to go to find support and the lack of clarity surrounding institutions’ and funders’ specific responsibilities delayed or prevented many students from receiving the assistance they were entitled to.

Inflexible funding arrangements were another key area of concern for participants. 10% reported limited or non-existent sick leave from their funder and many felt they did not have the freedom to work at a pace appropriate to their condition. Part-time doctoral study is an option offered to all UKRI grant holders. However, student stipends are paid on a pro-rata basis, making part-time study financially inaccessible to the majority of disabled students who are unable to supplement this reduced income with an additional job. Overall, the report revealed that students with a flexible and accommodating funder were 1.5 times less likely to say that their PhD had affected their physical health.

However, Quinn is keen to emphasise that many of the study participants also shared positive experiences and examples of good inclusivity practice. ‘The strength of the supervisory relationship is really core and key and we found that students with understanding supervisors were 12 times more likely to feel well-supported,’ he explains. ‘Many supervisors have asked for training to help them better support students with disabilities and we need to build on this proactivity.’

Overall the study identified four broad areas for improvement – accessing appropriate assistance, strengthening crucial relationships, adapting the physical and sensory environment, and pacing – and the team made a series of recommendations to help institutions and funders address each of these elements.

Emrys Travis, a disability and accessibility specialist at the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), is in complete agreement with Quinn’s findings. ‘Disability inclusivity in the chemical sciences is a strategic priority for the RSC, and DSUK’s report reflects much of what we have learned from research with our disabled chemistry community,’ they say. ‘The individual testimonies in particular highlight the wide variety of barriers facing disabled postgraduate students, and the cost to them and to our academic community if we fail to address these barriers. DSUK’s recommendations underline the importance of marrying individual support with a proactive approach to creating accessible environments for all.’

‘We hope our report will give disabled students a voice and help institutions and funders focus on important issues which merit further attention,’ concludes Quinn. ‘If you can achieve a more inclusive research environment for students with disabilities, that’s going to benefit everyone – people with caring responsibilities, people from different socioeconomic backgrounds, people from different cultures. I can’t see a way that it wouldn’t help.’

1 Reader's comment