Scientists at the University of York have found chemical evidence of the trade in wine in Sicily from the ninth until the 11th centuries, when the Mediterranean island had Islamic rulers who were forbidden by their religion to drink alcohol. They say their method to tell if ancient pottery containers held wine or other grape products can be used on artefacts from almost any time and place, and could help researchers chart the use of wine over thousands of years. Although the use of wine in Islamic Sicily is attested by historical evidence, ‘we have established this very robust criterion with chemistry, and you can apply this to earlier periods where we have no idea if wine was produced’, says Léa Drieu, who carried out the analysis.1

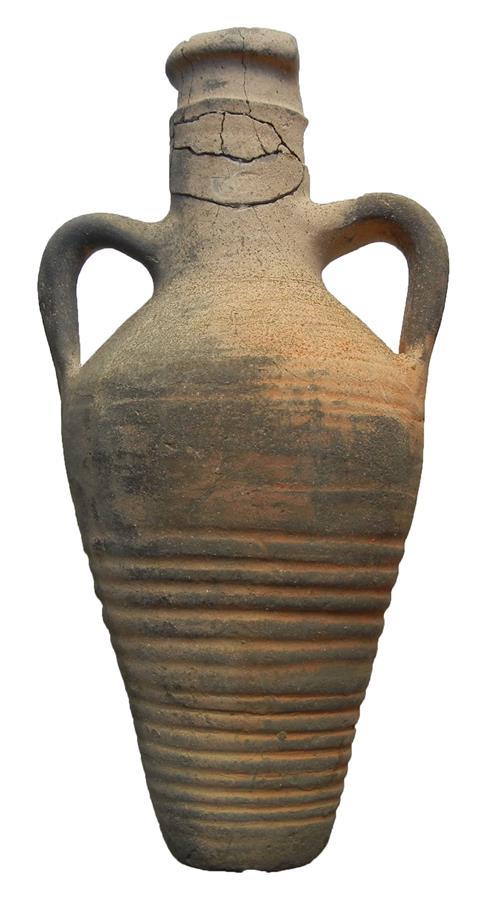

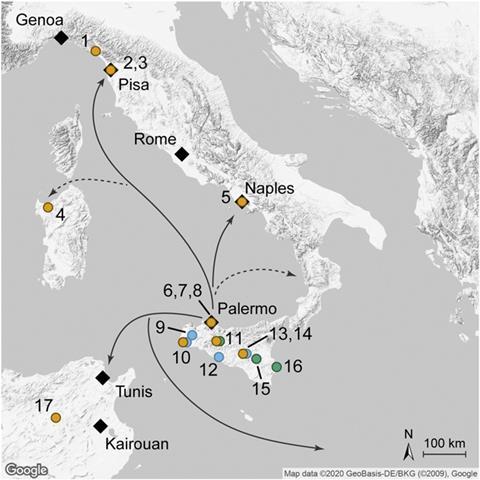

Sicily was a major producer of wine before the ninth century, when it was part of the Byzantine Empire. Distinctive Sicilian amphoras – large pottery jars – traditionally used for wine have been found in Sardinia and the Italian city of Pisa, suggesting Sicilian wine was exported throughout the Mediterranean. But Sicily suffered attacks by Muslim Arabs from the eighth century, and the whole island was under Islamic rule by 902. Sicily’s Islamic period lasted until the late 11th century, when the island fell to Norman invaders.

The new method for determining if a pottery container held wine or other grape products hinges on traces of fruit acids absorbed by the pottery itself. Although the liquid in the container and its organic residues may have disappeared or become corrupted by age, these traces persist within the walls of the container, the researchers write.

After studying more than 100 amphoras produced or imported into Sicily between the fifth and 11th centuries, the researchers determined the levels of tartaric acid and malic acid that they absorbed. They used this as indicator of whether or not an amphora had been used to store grapes, either as wine or unfermented juice, or perhaps as raisins or vinegar, which are common ingredients in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cuisine.

Grapes have high levels of tartaric acid, which increase as the fruit ripens, and correspondingly low levels of malic acid, which decrease as grapes ripen – and the ratio between them gives a distinctive signature for the presence of grapes, the researchers write. They then used archaeological criteria to distinguish which amphoras had held wine, unfermented juice, or other grape products.

The study determined that the Islamic rule of Sicily did not lead to a reduction in the amount of wine traded – in fact, it increased over the period, suggesting that its Islamic community profited from selling wine to other parts of the Mediterranean. But the researchers stressed that there was no evidence that Sicilian Muslims actually drank the wine they were trading, which is prohibited by Islamic traditions.

Archaeologist Hans Barnard of the University of California Los Angeles, who has studied ancient wine-making2 but was not involved in the latest research, notes the technique depends on the preservation of the pottery artefacts used. ‘Both tartaric and malic acid are easily water-soluble and will readily leach out of vessels,’ he says. The ratio of the acids could also be altered by microbiological activity. However, these issues could be overcome by carefully selecting the artifacts for testing. ‘When applied with appropriate care, this method will likely prove a valuable addition to the field,’ he said.

References

1 L Drieu et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2021, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2017983118

2 H Barnard et al, J. Archaeol. Sci., 2011: DOI: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.11.012

No comments yet