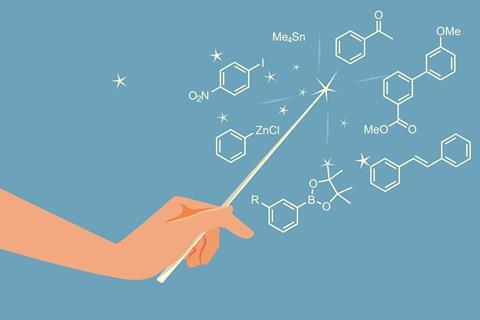

When new chemistry looks like alchemy or witchcraft, it’s worth taking notice

I will freely admit that it’s been a while since I learned organic chemistry for the first time, and I’m also willing to concede that this interval is growing ever larger. I think for any of us that learn such a body of knowledge, we think of our original training as the baseline, the standard, with everything coming later fitting in as some degree of new-fangled stuff.

Some of that new material becomes familiar over time, naturally. When I took undergraduate chemistry, the palladium-catalysed carbon-carbon couplings that are so much a part of synthetic chemistry had not really been discovered yet, and I well recall asking someone in the early 1990s if that stuff actually worked. But they’re part of the landscape now, as odd as they might have appeared at the beginning.

Seeing what looks like alchemy reduced to practice, with detailed instructions on how to do it in your own fumehood, that’s another feeling entirely

And those are the sorts of reactions that I am always on the lookout for. To take it beyond synthetic organic chemistry, those are the sorts of discoveries I’m fascinated by in general. When the metal-catalysed couplings appeared, they seemed otherworldly because (in many cases) they showed transformations that none of us had ever done before, that none of us had ever considered doing before. Connect one aromatic ring to another, as if they were snap-together building blocks? Witchcraft!

Some of the photochemistry reactions of the last decade or so bring on the same feelings, and I’ve seen some new reactions that do things such as install amine groups directly onto hydrocarbon backbones,1 or take tertiary carbons and flip their stereochemistry around.2 Those don’t fit into any category of synthetic chemistry tool I carry around in my head – they look like the sort of steps that you’d draw a red X through if an answer on an undergraduate examination paper showed them as part of a reaction scheme.

But these are just the sorts of discoveries you love to see, the ones that expand what you even thought was possible. You flip through the chemistry literature, and you see a better way to do this, and a better explanation for that, and a connection between these two other known quantities. All of that is fine, and sometimes more than fine. But seeing what looks like alchemy reduced to practice, with detailed instructions on how to do it in your own fumehood, that’s another feeling entirely.

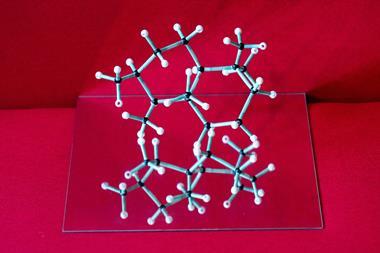

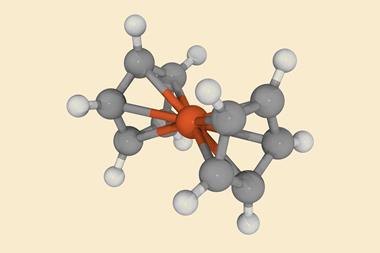

The underside is that some of these things can have a hard time getting published. Both the papers I’ve mentioned are from well-respected labs at famous institutions, and don’t think for a moment that this doesn’t help. R B Woodward himself was admonished by the editor of the Journal of the American Chemical Society that after seeing his proposed (and correct!) structure for ferrocene that: ‘I cannot help feeling that you have been at the hashish again’ (See Chemistry World, November 2020, p23). But he accepted the paper, because it was from Woodward. I feel sure that someone with less of a name would have had that manuscript rejected.

There are lists of Nobel-prize-winning discoveries in the sciences that were all turned down in their initial attempts at publication, among them minor little things like the Krebs cycle. (To be fair, a few of these were not because the discoveries appeared too strange, but because the editors and reviewers seemed to think that they were too mundane!). And would a chemist of lesser reputation than Barry Sharpless have managed to publish the concept of click chemistry so easily and prominently?

It’s also important not to fall into the opposite error of thinking that every extraordinary result is real. The signal-to-noise on revolutionary discoveries, taken across the whole of science, is not particularly good. As Carl Sagan put it: ‘They laughed at Columbus, they laughed at Fulton, they laughed at the Wright brothers. But they also laughed at Bozo the Clown.’ With organic chemistry, though, we have the very important advantage of being able to check things more easily than in many other fields. Bizarre-but-true reports are taken up faster and bizarre-but-false ones get demolished more quickly.

I almost regret that there isn’t a J. Weird Chem. for such things to appear in. But I welcome the pursed-lips, head-scratching, you-must-be-kidding papers wherever they show up. They remind us that the world is still young and that the future isn’t written down.

References

1. S V Athavale et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2022, 144, 19097 (DOI: 10.1021/jacs.2c08285)

2. Y-A Zhang et al, Science, 2022, 378, 383 (DOI: 10.1126/science.add6852)

No comments yet