Derek Lowe asks (with some trepidation): do drug companies need scientists at the top?

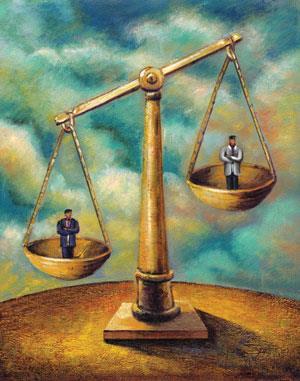

Here’s a topic that always gets people arguing: how much of a scientist should the chief executive of a biopharma company be? Many people – and they get going on this subject very quickly – are ready to denounce the business degree holders, the lawyers and the finance types who often run such businesses. If only these people understood science, why, things would have turned out differently.

I don’t think that’s completely wrong, and there are some hideous examples out there that can be brought in as evidence. But I certainly don’t think it’s completely right, either. There are deep ditches on either side of the road, ready to be steered into. Keep in mind, though, that as a scientist I’m hardly a disinterested party – of course, I think people should value what I find valuable and what I’ve chosen to do for a living, so my reflex is to say that well, of course a top executive should understand the science behind the business. But to what extent? A chief executive has several other things to do, many of which will not be assisted by a deeper understanding of (say) binding site interactions. It may sound callous, but that’s the sort of thing that the scientists themselves are supposed to be taking care of. Specialised knowledge is the whole point of an organisation. None of us would deny that the scientific aspects of drug discovery are capable of engaging all of a person’s training and intelligence, which makes drug discovery a task that should be delegated to those of us who do it full time.

The scientists know that they have to understand business, but the reverse doesn’t always hold

Don’t misunderstand me – I’m not saying that it’s perfectly fine for the person at the top to know nothing about science or medicine. I think that’s asking for trouble as well, because someone in that situation is at the mercy of what other people tell him or her are good ideas. What I’m saying is that knowing science and medicine thoroughly is no guarantee of success either and might actually increase the chances of failure if other skills haven’t been developed as well. Chief executives have to understand business strategy and finance too, and knowing something about marketing would certainly be useful. At many companies, they have a job akin to that of many university presidents: going out to raise funds and keeping the existing investors happy. That’s a subject no one gives out degrees in.

The perfect synthesis

What’s the right balance? That depends on the size of the company. Smaller ones tend to have executives who are closer to the science. This is surely a founder effect, and also reflects how a small biopharma company must make direct scientific progress in order to survive. Larger going concerns with more diverse businesses have a more diverse set of chief executive backgrounds. If they came up from the scientific ranks, good for them – but they’d better have learned how to talk to the stock markets, and how to evaluate both large financial deals and the people who are evaluating the deals.

If they came up from the legal, finance or marketing divisions, though, all is not lost. What I’d recommend there is some catching up on the scientific side of the business, and this is something that you rarely see. The scientists know that they have to understand business, but the reverse doesn’t always hold. The temptation is to take that delegation process mentioned above and use it as an excuse: ‘I have people to think about such things for me.’ Well, yes, you do, but that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be able to think about them at all for yourself.

This is a longstanding problem, and not only in the sciences. It’s always hard for the occupant of the highest slot on the chart to get an honest assessment of what’s really going on in the lower levels. There are too many incentives for people to tell them what they’d like to be hearing. The more chances chief executives have of being able to detect this (in others, and in themselves), the better off they’ll be. Knowing enough science and medicine to recognise a bogus development timeline, or to question a market size prediction (high or low!) would be an ability worth spending a little time to develop. Wouldn’t it?

No comments yet