On 29 January, two gatherings in two cities passionately discussed the same topic: international collaboration. But they couldn’t have been more different in tone.

In London, the UK parliament voted on a number of competing amendments to the EU Withdrawal Bill, with warring political factions pitching their favoured form of Brexit. The tone of debate was bitter and divisive, and sadly this reflects the overall tone of public discourse about the UK’s international relationships these days.

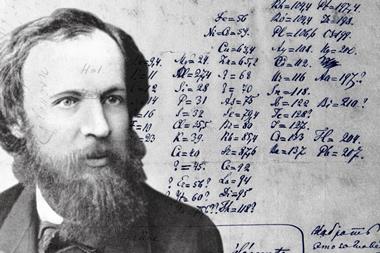

Meanwhile, just across the Channel at Unesco headquarters in Paris, I spoke alongside fellow representatives of science organisations at the opening ceremony of the UN International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT). It was a joyous celebration of international chemistry and a reminder that while global politics is currently focused on hardening borders, the global chemistry community enthusiastically transcends them – as we always have done.

The Royal Society of Chemistry is proudly leading the UK’s contribution to the IYPT celebrations. As Martyn Poliakoff and David Cole-Hamilton point out, it grew from a grassroots campaign to full UN recognition through the tenacity of chemists from many countries. There’s a phenomenal programme of events worldwide, and we will be leading a number of these in the UK and abroad.

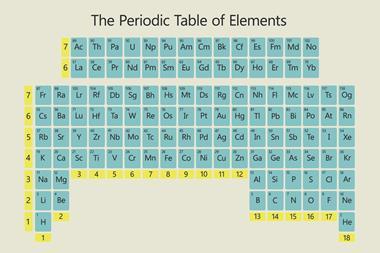

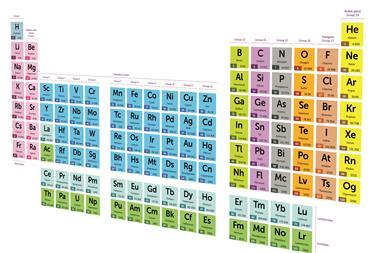

Every pupil studying chemistry learns from a periodic table – it’s a universal teaching aid and visually demonstrates chemical concepts like periodicity and orbital theory. The RSC already has (in my opinion) the best periodic table on the internet. So to support teachers throughout IYPT we’re creating complementary resource packs to help them explore the table even further with their students.

We know our wider community are keen to lead their own IYPT activities, so we have plenty of grant funding available. Applications so far include participation at the Edinburgh International Science Festival and creating interactive periodic tables for science discovery centres. Our grants are open to member groups worldwide so they can host local activities.

A wide range of audiences can connect with the most recognisable icon of chemistry. We’ll be touring a programme of public events around the UK, from lectures and storytelling to hands-on chemistry experiences. Peter Wothers of the University of Cambridge is curating an exhibition of periodic table history at our London headquarters. And we’re developing several high-visibility initiatives to engage with parliament and the media throughout the year.

Following the well-publicised EuChemS table of endangered elements, we’re commissioning research into UK households’ unused electronic devices. I know that my family has a few old phones and laptops collecting dust in the attic, and each of those contains some potentially recoverable gold, indium and other elements. Extrapolate that thought to every household in the country: how large an elemental treasure trove languishes in our collective lofts?

Governments, manufacturers and retailers have to make reuse and recycling much easier for consumers, and make the circular technology economy a national priority. This is not just protecting endangered elements for our needs today. What revolutionary technologies of the future – say, clean energy, or advanced medicine – might rely on the limited resources we have squandered?

To avert these future crises, we also challenge the chemistry community: what new materials might we create, or new scientific paradigms might we unearth? As a discipline we’ve successfully combined basic discovery with applied research for nearly two centuries, so I’m confident that chemists will be central to solving all the global challenges, including element scarcity. It’s taken us 150 years to build a periodic table with 118 elements – let’s make sure they’re all still on it in 150 years’ time.

No comments yet