Andrea Sella shares his favourite memories from exploring the history of lab equipment

Relive some of the highlights from Classic kit in the countdown to the 100th edition. Does your favourite feature?

Lovelock’s detector

James Lovelock has long been a hero of mine. My father, who attended the Stockholm conference that gave birth to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in 1972, gave me a copy of Gaia as a teenager. But I dithered over the article, even after Roger Highfield at the Science Museum gave me James and Sandy Lovelock’s email address. When I decided that Lovelock’s electron capture detector (ECD) had to be column number 100, I finally felt brave enough to get in touch. Lovelock not only showered me with stories, but also gently corrected several howlers in my draft.

For me, the ECD represents a device that produced a paradigm shift in our thinking. And, at a time when UK science is at a crossroads, it’s a story that underlines how the way we fund research, and the atmosphere you establish in a laboratory, is so crucial if you want to produce big-time science.

Read the incredible story of Lovelock’s ECD here.

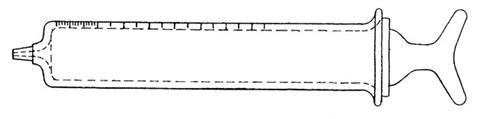

Lüer’s syringe

Researching the Lüer syringe was another adventure, which involved trawling through French patents and scans of equipment catalogues of the firm Wülfing-Lüer. While hunting for the name online, I came across a woman with the same surname, who turned out to be the widow of the last owner of the firm. She revealed the family legend that Jeanne Wülfing-Lüer had been the creative brains of the business. It was a bittersweet story: a business that flourished for two generations, then faltered and vanished. The Boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris, France, where Wülfing-Lüer was based, will never be the same for me.

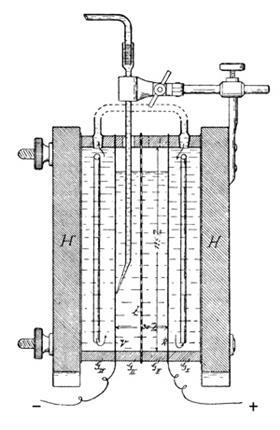

Luggin’s capillary

My friend Daren Caruana suggested that I investigate the Luggin capillary. Over many months I dug around in old journals trying to find a description, drawing a blank among Hans Luggin’s articles. An archivist in Karlsruhe, Germany, sent me a scan of an obituary for Luggin, which unfortunately was printed in a maddening 19th century Gothic typeface. However, this tipped me off to a connection to Svante Arrhenius, and to Luggin’s brief but intense friendship with Fritz Haber. When I at last found a diagram of the capillary in one of Haber’s papers, I knew I had another ripping yarn.

Abderhalden’s drying pistol

I remembered a forlorn and forgotten drying pistol, clamped to a rack in a corner of the lab, from my time as a young graduate student in Toronto, Canada. I decided this would be the focus of an article, and the trail led me to Emil Abderhalden. His story, with its mixture of politics, patriotism and fraud, gripped me like few others. I was sure that he had not invented the pistol, but when the trail ran cold I decided to write the article anyway.

About a year later, I found another early picture of the pistol, this time with a reference to its true inventor: Ludwig Storch. A friendly librarian in Minnesota, US, provided a scan of the original article that wasn’t available anywhere in the UK. Abderhalden’s name still leaves a slightly bad taste in my mouth.

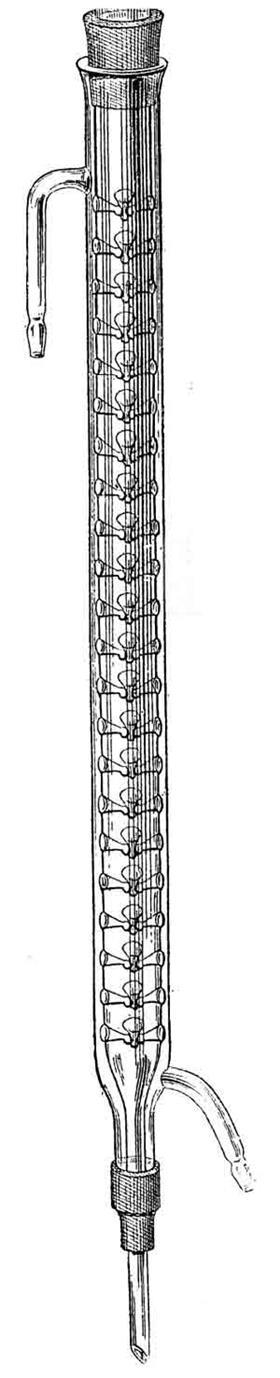

Vigreux’s column

I’ve used ‘the Vigreux’ to fractionate organic mixtures for as long as I’ve been a chemist, but my hunt for its inventor took a long time. I finally stumbled across a collection of photographs of assorted Vigreux-ware in a Belgian photolibrary. Accompanying them was a portrait of a glassblower. Could it be Henri Vigreux?

After calling various glassblowers in France without success, I spoke to Pierre Pignat in Lyon. He was a goldmine of information: his father had apprenticed with Vigreux. I emailed him the photograph. Minutes later Pignat confirmed that the man pictured was indeed Vigreux. To celebrate, I ordered a copy of Vigreux’s Le soufflage du verre dans les laboratoires scientifiques et industriels, a guide to help researchers make their own glassware, from an antiquarian book dealer.

Büchner’s funnel

Researching the Büchner funnel bothered me for months. It was only when I found the original description in the Chemiker Zeitung that I spotted the address of its inventor: Pfungstadt. Looking on a map, I realised that it was a small town on the outskirts of Darmstadt, Germany, the birthplace of the playwright Georg Büchner. It could not be coincidence. This discovery led me to a town council website describing the Büchner family, and local historian Peter Brunner, who provided a wealth of still unpublished photographs and other information about the unfortunate Ernst Wilhelm Büchner. His tragedy still moves me.

Andrea Sella teaches chemistry at University College London, UK

No comments yet