Get real

You find a lady clad in a filthy ragged coat. She is holding onto something in her right hand and flipping it at a regular pace. She is mumbling something, almost as if chanting, and her eyes are transfixed on something in front of her. What separates her from what she is staring at is a glass window.

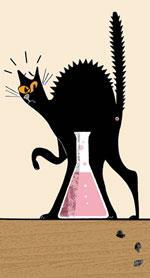

The scene is not set in a Buddhist monastery in Cambodia or a busy temple in India but in a synthetic lab. The lady is a chemist wearing a stained old lab coat, holding her lucky charm and staring at the flask in her fume cupboard, in a hope that her reaction works this time.

Of course, no force of our minds can bend the way the molecules in that flask will behave, and nor will the lucky charm give us that extraordinary power. Nevertheless, I’ve seen many otherwise rational chemists fall for these irrational desires.

When we are involved in any scientific pursuit, we are expected to be rational. The business of science will work only if there are certain set rules by which we pick our way through the empirical data, construct new hypotheses and argue them. Rational thought forms the basis of all that is science.

But when you spend long hours working towards making something work by hook or by crook (total synthesis of natural products), or come across phenomena that you aren’t able to explain (the reaction that only ever worked once) a surprising number of us can’t help but fall for such irrational behaviours despite years of scientific training. At which point, the relationship between science and rationality becomes somewhat skewed.

We spend long hours debating the details of how an electron would be transferred from one atom to the other (reaction mechanisms) and then end the discussion by saying, ’touch wood, at least we have the product’.

We meticulously plan our scientific strategies ensuring that there are no logical loopholes and then we take a holiday because we don’t want to perform that critical reaction on Friday the 13th.

We put in endless efforts to build molecules with useful biological properties (drugs like Taxol), and then opt for an old wives’ tale of a traditional remedy or, God forbid, a homeopathic concoction when we suffer from cold or flu-like symptoms.

We publish papers in internationally renowned peer-reviewed journals, but we will not send that draft to Nature today because a black cat crossed the street on the way to the lab.

Rationality is that principle by which we act to maximise the expected performance given all the knowledge we possess. As a scientist, it pains me to see other ’scientists’ using the scientific method in the planning of their experiments but not in evaluating things in everyday life. When confronted, they offer a range of equally lame excuses: ’how does it matter?’; ’it’s essential to separate my work from my life’; and even ’it is not necessary that the way I think about my experiments should also be the way I think about everything else’.

It does matter. It matters because, as Jean-Marie Lehn, winner of the 1987 Nobel prize in chemistry, once said: every result you produce adds a stone to this big construction called science. If we build science in order to benefit humanity, shouldn’t people use the scientific way of thinking to benefit their own lives in the process?

I shudder to think how future generations might look back at our lives and chuckle at how our irrationalities actually stopped us from achieving the goals we would otherwise have achieved.

Akshat Rathi

No comments yet