Keeping up with the literature is impossible, says Derek Lowe.

You should be keeping up with the literature, you know. And you should be flossing your teeth. And checking the air pressure on your tyres. There’s probably some insurance or tax paperwork that you’ve been putting off, too, so you might as well get on with all of these at once. You’ll feel better about yourself, honestly.

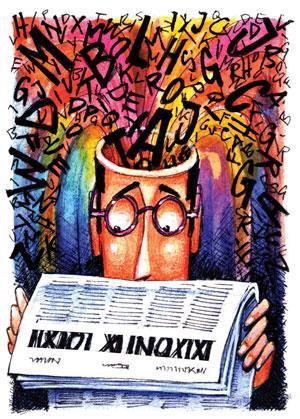

The literature situation isn’t quite that bad, but if you get chemists in a confessional frame of mind, they’ll probably tell you that they really don’t read the current journals as well as they ought to. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who thought that they were keeping up well enough. One of the problems, of course, is that the literature itself is a geyser, a phalanx of firehoses, and it never stops gushing out information. There are more journals than ever before, publishing more papers, and they’re coming from all directions at once.

The literature is a geyser, and it never stops gushing out information

But most of this is junk. If you find that too strong a term, then lower the size of the junk pile and reassign some of it to the ‘doesn’t have to get read’ pile. That is surely the largest one; it’s where all the reference-data papers go, the ones that no one looks at until their own research bumps into the same compound or topic. There’s nothing wrong with such papers, and publishing them is actually a key part of the whole structure of science (since you never know what might come in handy or turn out to be important). But you really don’t have to read these things. In fact, given their number, you can’t.

So the important question is what you actually do have to read. That list begins with what’s relevant to your current research, naturally, and you’re better off being rather broad-minded about what papers those might be. Then there are new methods and techniques from other areas that you might be able to use, which will be an even broader category. Add to those the titles or graphical abstracts that catch your interest for some other reason, and you’ve got as much (or surely more) current literature than you can handle.

Personally, I use an RSS reader with feeds from the various journals. That puts everything in one place, and lets me scan the new articles relatively quickly by scrolling through a list, marking ones that I might want to come back to later. It can induce despair, true, to go away for a few days and return to a notification that I have 748 unread articles, but it takes less time than you’d think to make that figure go down again.

In odd moments at my desk I’ll scroll through another run of articles, and soon I’m back at the frontier. There is a ‘mark all as read’ button, which can be applied to individual journal feeds, or even to the whole tottering stack, but I recommend caution. Once you start using it, it can be difficult to stop. In the old days, the joke was that people thought that they’d actually read a paper when all they’d done was make a photocopy of it at the machine, so it’s worth remembering that marking a paper as read does not necessarily mean that it’s been actually, well, read.

But there’s only so much time in a day, and only so much of that can be spent looking at new papers. That leaves many, many journals with which I don’t stay current at all. No doubt I’ve missed some interesting things from time to time, but the signal-to-noise ratio varies widely across the scientific literature, and many journals are just not worth the time it takes to sift through them as the papers appear. (I’ll pass over the ones that are not even worth reading at all; that’s another problem entirely).

If you haven’t admitted these constraints to yourself, give it a try. It’s actually quite liberating. You can even check what percentage of papers in a given feed you’re actually looking at in detail, and decide for yourself if it’s a good use of your time to scan the thing at all. That assumes, of course, that you’re actually looking at things that interest you, rather than scrolling past them in hopes that they’ll go away. An RSS reader will not solve that problem for you!

No comments yet