Meera Senthilingam

This week, Brian Clegg reminisces about a simple yet explosive compound.

Brian Clegg

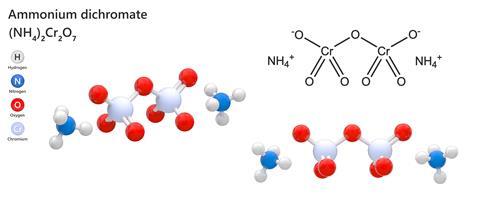

Of all the chemical compounds you could find in a chemistry set in the olden days before everything was health and safetyfied, perhaps the most satisfying in its simplicity was ammonium dichromate. This relatively complex inorganic compound combines two ammonium ions with the doubly negative Cr2O7 to form a rather attractive orange crystal that looks as innocuous as copper sulphate. But set light to it – surprisingly easy to do for a substance in crystalline form – and it spews out large quantities of feathery, dark green chromium oxide powder with a host of bright orange sparks and enough impressive force to give it the nickname ‘Vesuvian fire.’ Forget model volcanoes powered by sodium bicarbonate and vinegar, an ammonium dichromate volcano is the real deal.

To be fair to the chemistry set police, ammonium dichromate is an irritant, is poisonous, is almost certainly carcinogenic and is liable to explode if heated in a sealed container. The crystal structure is thermodynamically unstable, so given the trigger of a flame or sufficient heat it will begin an exothermic reaction that will produce a large expansion in volume as most, but not all of the dichromate converts to the oxide. In the process, nitrogen is given off, and the reaction is sometimes used in laboratories to produce purer nitrogen than can easily be extracted from the air.

The compound starts life as the naturally occurring mineral chromite, FeCr2O4, which is roasted in a kiln with sodium hydroxide and calcium oxide to produce sodium chromate. The main aim of this is then to produce basic chromium sulfate, an essential for the leather tanning industry, but some is processed via sodium dichromate to produce the ammonium salt.

Industrially, ammonium dichromate is a bit of a ‘yesterday’s compound’. In the early days of photography, it was one of a batch of chemical supplies – usually hazardous – that were employed to capture an image. The most direct use was in gum bichromate photography (bichromate is just an older, alternative term for dichromate).

Ammonium dichromate will always be a bit of a show-off, a compound that will always deliver thrills and spills

The process dates back to the 1850s and makes prints that can be full colour or monochrome. The approach taken is to coat paper in a mix of a pigment – typically a watercolour paint – and gum arabic, which is the sap of the acacia tree, though some modern users substitute PVA glue for the gum. The layer is then treated with ammonium (and sometimes potassium) dichromate, which makes it light sensitive, oxidising the gum to hold the pigment in place where light hits it. After exposure to an image (through a colour filter if a full colour result is required) it is washed in water, which takes away the pigment that has not had light exposure. To add extra colours, the process is repeated in layers with different pigments, producing a striking, more painting-like image than a traditional photograph.

Gum bichromate is only used today by specialist enthusiasts, as is another photographic use of ammonium dichromate, cyanotype sun printing. Here the compound is mixed with ammonium iron oxalate and potassium ferricyanide and soaked into paper. Once that paper dries it is photosensitive, turning blue on exposure to sunlight. Images are usually made by partly screening the paper with objects to form negative shadows.

Although unlikely to be used much now, the pyrotechnic industry did incorporate ammonium dichromate into some of its fireworks, both on its own in early indoor fireworks (before it was considered too dangerous) and in a mix to act as an oxidiser and expanding propellant.

We can see the same gradual withdrawal from use in another of the applications of ammonium dichromate. Dichromates proved effective mordants in dyeing. A mordant was originally a clasp or the buckle of a belt – something that held fast – and the term was transferred to the dyeing industry, where they wanted a way to make dyes hold fast to materials that naturally repelled them. The mordant acts as a kind of intermediary, forming a complex with the dye that will bond to a fibre of the fabric. Because there are other equally effective but less dangerous mordants, ammonium dichromate is now rarely used.

One final application which disappeared far more suddenly than the mordant was to help in the production of screens for TVs and computers. In effect, the dichromate was used in a similar process to gum bichromate photography to attach clusters of the phosphorescent material to the screen as pixels. The surface was coated with the mix, then exposed to light with a shadow mask that created the pattern of dots on the screen before washing away the intermediate material. But the introduction of LCD, plasma and LED screens has practically destroyed the market where ammonium dichromate had its last hi-tech application, leaving phosphor-based screens a rarity for specialist users.

We have to accept that despite the apparent innocent beauty of those glittering orange crystals, ammonium dichromate is too unsafe to be a plaything. But under controlled conditions, that gushing volcano reaction can still produce a wide grin on the face of the most cynical of chemists. Ammonium dichromate will always be a bit of a show-off, a compound that will always deliver thrills and spills.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Brian Clegg, with the volcanic chemistry of ammonium dichromate. Next week, things become metabolic.

Nate Adams

The cytochrome p450s group of proteins are possibly the most important molecular machines within our cells. They are the enzymes which start off the process of breaking down, or metabolizing usually toxic or dangerous molecules that our bodies don’t want or no longer need.

Meera Senthilingam

And discover the chemistry behind this by joining Nate Adams in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet