US FDA advisors vote against approving Biogen’s aducanumab on the basis of incomplete data analysis

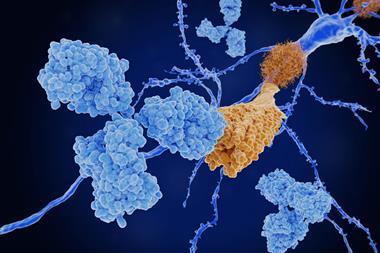

Biogen’s evidence surrounding the effectiveness of its experimental Alzheimer’s antibody, aducanumab, has been roundly criticised by a panel of independent experts advising the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The company had submitted the treatment for regulatory approval after a controversial re-analysis of halted clinical trials suggested it might be effective at slowing cognitive decline at high doses.

The FDA’s internal review appeared sympathetic to Biogen’s interpretation of the clinical outcomes, but deemed the statistical evidence unconvincing. The advisory panel was similarly unimpressed by the analysis, voting overwhelmingly against recommending aducanumab for approval. The FDA is not bound to follow the panel’s advice, and will make its final decision about the drug by March 2021.

‘There was a strong disconnect between two aspects of the FDA review,’ says Paul Aisen, neuroscientist at the University of Southern California, US. ‘A positive clinical review, and a negative statistical review. I haven’t seen that before.’

Biogen stopped recruiting new patients to two phase 3 trials (dubbed Emerge and Engage) in 2019, after an interim futility analysis saw no signs of significant clinical benefit. Subsequent analyses, with more data from the patients already on the trial, suggested that a subgroup of patients in the Emerge trial, who received the highest dose for longer, showed reductions in clinical dementia scores.

Biogen’s application for approval is based on this subgroup analysis, and offers arguments as to why effects in the Engage trial were not so pronounced. The FDA’s reviewers described this analysis as ‘highly persuasive’. In contrast, the FDA biostatistician’s report noted that ‘the totality of the data does not seem to support the efficacy of the high dose’. He continued: ‘There is only one positive study at best and a second study which directly conflicts with the positive study.’ The advisory panel’s decision sided strongly with the FDA’s biostatistician, that the data as a whole are not enough to support approving the drug.

The FDA got its hand slapped by these panel members for being too collaborative and too engaged with the company

Alzheimer’s researcher Cynthia Lemere at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, US, was frustrated by the panel’s focus on the primary endpoint only, while ‘there was clinical benefit in [the Emerge trial] across the board in every cognitive and functional domain’.

She says the panel refused to accept subgroup analyses involving those who received the high dose of aducanumab. The panel ‘seemed upset that they were being told to ignore the negative [Engage] trial,’ when asked to assess [Emerge] alone, Lemere says. ‘Most panellists appeared to base their answer on both trials.’

The statistical hazards of re-analysing clinical data in ways that were not initially designed into the trial are well documented. Any decision based on such analysis should be scrutinised particularly carefully. ‘The FDA got its hand slapped by these panel members for being too collaborative and too engaged with the company,’ says Lemere.

One thing we can say for certain is that this is not a drug which has a major effect on the clinical progression of the disease

Lemere has worked on medical educational material about Alzheimer’s for Biogen, and serves on the medical and scientific advisory group of the Alzheimer’s Association. The association submitted a statement to the panel supporting approval of aducanumab, highlighting the ‘drastic need to offer relief and support to the millions of Americans impacted each day by the crushing realities of Alzheimer’s.’ Lemere predicts that the FDA will likely ask for additional phase 3 studies, which could take four to five years. ‘It is rare that the FDA would go completely against the panel,’ she says, although they could opt for conditional approval, requiring Biogen to monitor patients and produce more data for later review.

John Hardy at University College London, UK, says many fellow Alzheimer’s scientists he is in touch with are struggling to decide whether approval is justified for aducanumab with the data to hand. He sympathises with FDA’s predicament. Nonetheless, such post hoc analyses ‘even if plausible, are dangerous,’ he adds.

‘One thing we can say for certain,’ says Hardy, ‘is that this is not a drug which has a major effect on the clinical progression of the disease.’ Any effect it does have is likely to be relatively small. Nonetheless, with no other effective treatments for Alzheimer’s, the FDA will be under pressure to approve aducanumab. Hardy points to the drug tacrine (Cognex) as an example of an Alzheimer’s drug that was approved under pressure on the basis of poor trial data and withdrawn in 2013.

Aisen says the interim analysis has done a huge disservice to everyone. ‘We set up our trials to give us an answer at the end of the trial; and then we try to make a decision in the middle,’ he says. Such futility analyses are intended both to save companies money and reduce risks to volunteers if trials are obviously hopeless, but by definition lack the statistical power to judge small effects. ‘We should be much more cautious in interpreting [futility analyses], because they are based on incomplete datasets,’ Aisen says.

No comments yet