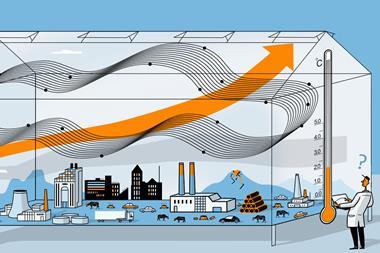

Under increasing pressure, big firms are making sweeping climate pledges. How do they stack up?

Report after report tells us that, to have a chance of keeping average warming to no more than 1.5°C, oil and gas will have to be kept in the ground. The companies producing hydrocarbons are setting net zero targets for 2050, yet none are deemed to be on track to meet their commitments. The World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) says these companies will burn through the sector’s 1.5°C carbon budget by 2037.

Although many countries have set net zero targets, state-owned companies are the biggest emitters, and few have committed to net zero. Just ahead of the Cop26 climate conference, Saudi Arabia said it would bring emissions down to net zero by 2060 – although it has no intention of stopping oil and gas production. State-owned Saudi Aramco said it would achieve the aim ten years earlier, but only for emissions it directly controls.

Investors and climate activists have been trying to force the pace – snatching seats on boards and taking big emitters to court. Earlier this year a Dutch court ordered Shell to cut its emissions by 45% by the end of the decade, rather than continue with what it labelled as ‘undefined’ and ‘intangible’ plans. Shell said it would appeal the ruling, but has now pledged to cut absolute emissions from its operations by 50% by 2030. The UK government – host to this month’s climate talks – faces action from campaigners angered at continued state aid for the industry.

Terms and conditions apply

The targets companies set cover direct emissions from their operations including onsite energy use and flaring (scope 1) and the energy they purchase to power offices (scope 2). Indirect emissions, from the use of products, goods and services purchased or waste disposal are covered by scope 3.

A new sector reporting standard, developed by the independent Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), comes into force in 2023. It’s sorely needed because reporting and target setting is inconsistent: different elements of the value chain are included or omitted; not all greenhouse gases are covered; framing may be in terms of intensity (CO2 emitted per barrel of oil; or per unit of energy produced) rather than as an absolute measure of carbon dioxide (or equivalent) emitted.

Axel Dalman, an analyst at financial think tank Carbon Tracker, says given ‘oil and gas companies produce something that – however you spin it – is going to emit something at the end of the day, you need to set targets on an absolute basis’. He adds, ‘if you set just an intensity target, you can just add some green energy on top and maintain your current conditions. And that doesn’t really fit with the finite nature of the global carbon budget’.

Untangling the targets

This visualisation shows how a selection of companies have laid out their initial (2025-2030) and longer term (2050) targets in terms of both absolute emissions and emissions intensity. Scroll through the graphics to see how they compare

Emissions intensity refers to the carbon emissions per unit of product. This visualisation does not fully represent the nuance and complexity of targets set by these companies, it is intended to give an overview of the scope and variability in the way companies are approaching target settingHow do we even know if the targets companies set are consistent with the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement?

The Science Based Targets initiative is working on methodology that the oil and gas sector can use, but until that’s available companies are developing their own approaches. Shell and BP, for example, publish their own scenarios of possible transition trajectories over the next 30 years.

Robin Lamboll, research associate in climate science at the Grantham Institute, is part of a team that has compared models (including those of the International Energy Agency), all with differing uncertainties. From an emissions perspective, ‘they’re not completely unreasonably generous in their climate models, but they do seem to be choosing climate models that are on the lower end of the temperature response, allowing them to have slightly less substantial cuts to emissions, and still reach certain climate goals’.

The majority of the scenarios assessed overshoot the 1.5°C warming limit ‘by a significant margin’.

If assets are being sold to private equity holders, or just to companies that aren’t as transparent, then it doesn’t reduce absolute emissions

Language is another issue. Chevron has an ‘aspiration’ to achieve net zero in its production and processing operations by 2050. Shell’s net zero target has a broader scope, covering not only operations but the use of the products it sells, with the caveat that it can only proceed ‘in step with society’.

BP is aiming for a 20% reduction of emissions in its global operations by 2025 and a 30–35% reduction by 2030 on its route to net zero by 2050. BP’s targets cover scope 1 and 2 emissions from upstream operations; and scope 3 emissions from production – with the exception of Russia’s Rosneft, in which it has minority share.

Italy’s ENI upgraded its aims to halve scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2024 (compared to 2018), bringing them to net zero by 2030, and says it will decarbonise all its products and process by 2050. But it’s recently made some big oil discoveries.

Scope of the problem

This visualisation shows the distribution of selected companies’ emissions across the different classes of direct (Scope 1, 2) and indirect (Scope 3) emissions. Scope 1 covers operational emissions, Scope 2 is purchased power, Scope 3 takes in indirect emissions from a range of categories including emissions from products sold.

BP Scope 3 emissions reporting excludes its share in Russia’s Rosneft

Shell Scope 3 reporting includes its own products (452MtCO2e) and 3rd party products it sells (602MtCO2e)

How will companies meet their targets? BP’s chief executive was the first to say last year that the company will cut oil production by around 40% by 2030.

Its already begun divestments including selling its petrochemicals business to Ineos. Others too are selling, but interests are being bought by other energy firms and private equity. An analysis by Fitch suggests fossil fuel investments by private equity firms have dwarfed renewables investment over the past decade.

Charlotte Hugman, research lead for the Climate and Energy Benchmark at the WBA says ‘when you look at the bigger picture, if these assets go under the radar – if they’re being sold to private equity holders, or just to companies that are much smaller and maybe aren’t as transparent, then it doesn’t reduce absolute emissions.’

While oil declines as a proportion of portfolios, gas is seen as a transition fuel, filling in for intermittent renewables and being used to produce hydrogen in conjunction with carbon capture and storage. That route will help lower refinery emissions – which today contribute 6% of all industrial emissions. Shell has plans to reduce its refineries from 13 sites to 6 chemicals parks, recycling wastes to make biofuels for example. But it won’t say how much of an impact this will have on emissions.

Around the North Sea, companies are involved in developing major projects to decarbonise industrial clusters: transporting CO2 for storage in depleted oil and gas fields or saline aquifers; and producing hydrogen for industrial use. Last month, the UK government announced two clusters in the north of England – Hynet led by ENI; and the East Coast Cluster – involving BP, Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies – as its leading candidates for a share of public investment.

The sector is also pursuing electrification of offshore platforms. The UK’s Oil and Gas Authority estimates electrification could cut platform emissions by 2-3 million tonnes by 2030, the equivalent of 20% of today’s production emissions. Andrew Wright, emissions manager at Repsol Sinopec, told a webinar organised by Oil and Gas UK, that ‘the perfect world solution would be that you get all your power from a renewable source – offshore wind – but because of the requirement to have consistent power, the realistic option is to have it backed up with a route back to the grid as well.’ As the grid becomes less emissions-intensive, so do offshore assets, he adds. Earlier this year, Shell, BP, TotalEnergies and Harbour Energy announced a project to electrify offshore assets, while BP has electrified its onshore facility in the US Permian basin.

Efficiency measures such as using combined heat and power at refineries also cut emissions. But big reductions will come from cutting methane and reducing flaring. Flaring is used to get rid of gas that can’t be captured or used, or as a safety measure. The World Bank estimates flaring produced 400 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions in 2019 and has set up an initiative to end routine flaring by 2030. Many European companies have already committed to eliminating it by 2025.

Cutting methane could provide a crucial win in slashing emissions over the coming decade. That’s because, while methane is 84 times as warming as carbon dioxide, it has a relatively short life. Cop26 saw over 100 countries commit to the Global Methane Pledge, aiming to reduce methane emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. At a company level, the 12 members of the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) have pledged to cut methane intensity of their upstream operations to ‘well below’ 0.2% by 2025. But members are moving at different speeds, ENI has cut methane emissions in its upstream sector by 90% between 2014 and 2020; ExxonMobil reports a 15% cut in the 4 years to 2020, taking it back to levels it reported in 2012.

While net zero targets are essential, it’s the quality of the transition that counts, says Hugman, ‘What are companies doing in their planning? And importantly, are they putting their money where their mouths are? Is there the sufficient capital expenditure in, for example, low carbon technology and in research and development for new tech? Do the carbon plans have milestones – ideally five-yearly intervals – for what companies are going to be doing, not just what they say they commit to achieving in nearly 30 years’ time.’

WBA uses sector-specific methodology developed by environmental disclosure charity CDP and the French Agency for Ecological Transition to assess a company’s climate strategy and performance. It finds that not a single company is taking the actions required to be on a 1.5°C Paris-aligned pathway.

They should be investing 77% of capital budgets into low carbon technology. Instead, the average is around 7%, among 30 companies of the 100 analysed which do report the figure. ‘Although its sensitive information, without it companies can’t be held to account on how they’re going to implement their plans,’ says Hugman.

TotalEnergies – which changed its name from Total to reflect how its portfolio will transition to low carbon technologies, came out on top in terms of investment commitments. It plans to put $60 billion into wind and solar production to have 100GW capacity by 2030. Some of its investors voted against the plans as not ambitious enough.

BP is pursuing solar capacity through its joint venture Lightsource BP and plans to have 25GW installed capacity by 2025 – compared to 3.8GW developed since 2010. This year, BP entered the UK’s offshore wind sector and will jointly develop two projects with a combined generating capacity of 3GW. In the US offshore market, it’s teamed up with Equinor – paying Norway’s oil and gas company $1.1 billion for a 50% share in 4 projects.

Elephants in the room

The missing piece of the jigsaw is scope 3, contributing 80% of greenhouse gase emissions. Scope 3 is described by 15 categories along a product’s entire value chain, but the bulk comes from the use of sold products – such as emissions from petrol burned in cars or kerosene in aircraft. Some of these will be scope 1 emissions for end users, such as airlines.

Protecting a forest is not actually taking CO2 out of atmosphere. A credible plan would rely more on existing technologies like switching to renewables or selling less fossil fuels – stuff that you can actually touch

Speaking during Bloomberg’s Sustainable Finance Week, BP chief executive Bernard Looney acknowledged the challenge in cutting emissions from product use. In 2020, at the height of the pandemic, energy use fell just 4% illustrating that ‘this is a very complex problem to solve.’ Solutions require governments and customers too.

ExxonMobil only agreed to report scope 3 emissions earlier this year, after it bowed to investor pressure. Even then, it said the figures ‘do not provide meaningful insight into the Company’s emission-reduction performance and could be misleading in some respects’.

Shell points out that while its scope 3 emissions are the scope 1 emissions of product users, there’s no equivalence in reporting mitigations. So, if an end user stores or compensates for emissions there’s no equivalent reduction on the scope 3 balance sheet of the supplier. It’s working with standards-setting bodies to address this.

Conoco Phillips doesn’t set targets for scope 3 because ‘we do not control how the raw materials we produce are transformed into other products or consumed.’ Both it and Chevron want to see carbon pricing policies to help tackle Scope 3 emissions.

So how do companies intend to cut the pollution their products cause – apart from by producing less of them?

The answer seems to be through offsetting and carbon capture and storage. Shell aims to capture 120 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions each year by 2030, through nature-based offsets. It has invested in projects around the world, to offer ‘carbon neutral’ LNG shipments and carbon neutral lubricants. It aims to offset the entire lifecycle emissions of these products and says the carbon credits it has purchased are independently verified by standards bodies.

Similarly, ENI plans to offset 40 million tonnes a year by 2030 by planting trees. BP doesn’t intend to use offsets before 2030, but thereafter these are unquantified. How much land is going to be needed for these projects is unclear and nor is it certain that in a warmer world, forests will still be sequestering carbon.

‘This is like a Swiss cheese of problems, there are so many issues,’ says Carbon Tracker’s Dalman. ‘Protecting a forest is not actually taking CO2 out of atmosphere. And in a world of rising temperatures where wildfires are becoming more frequent the trees might not even be there [in future]. A credible implementation plan would probably rely more on existing technologies like switching to renewables or selling less fossil fuels – stuff that you can actually touch.’

This month’s climate summit aims to take decisions that will put the world on a trajectory to avoid the most damaging impacts of warming – will some of the biggest businesses on the planet take the steps to implement them?

No comments yet