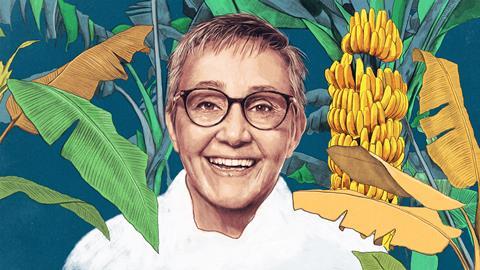

The atmospheric chemist who dared to dream big and returned home to Beirut to become an environmental activist

Najat Saliba is a professor of atmospheric and analytical chemistry at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon. She also directs of the school’s Environment Academy, which publicises environmental problems and works with local residents to develop solutions. In 2019, she made BBC’s list of 100 inspiring and influential women because of her environmental activism.

My dad was a banana farmer, and so all of our weekends and days off were spent helping him, or just spending time on the banana plantations and the citrus plantations. We also had land by the sea, so we always sat on the sand contemplating and really enjoying nature. There were six kids, I was the eldest daughter.

Unfortunately, when I was 14 the civil war broke out in Lebanon and we had to leave our home – not once, not twice, but four times. We would make it home and then be forced to leave again. That lasted until I was 24. It made me a totally different person, appreciating life and appreciating all the things that you usually take for granted. You realise it can all be stripped away from you.

I wanted to be a teacher all my life, but never thought I would be a researcher at a university. Honestly, I wouldn’t dare to dream that big because I was a girl, and my dad was not at the beginning supportive of women going to school and getting a higher education. And so, the farthest I could go with my dream was to become a schoolteacher.

I was supposed to fly to Lebanon on September 11, 2001, after I accepted a job at the American University of Beirut. I was living in Los Angeles then and was moving back to Beirut. As I turned on the television and saw people fleeing – terrified and completely covered with dust – and so much destruction around the Twin Towers, I had this flashback to the civil war in Lebanon. It was for me a déjà vu that was very painful. I postponed my travel for a week.

The only thing I saw was deterioration of the environment

I started collecting data on atmospheric pollution, trying to understand the levels of pollution and the chemical composition, and how long-range transport of dust and sandstorms will affect the local air pollution. Collaborating with horticulturists, for example, and people from the agriculture department, I started seeing the challenges with soil chemistry, and soil pollution. I also saw changes in the hybridisation of some plants over the years, and how much climate change has affected their chemical content.

I documented, measured and reported on the pollution in Lebanon for the longest time, and the only thing I saw was deterioration of the environment. There was no action taken by a government that was full of corruption. And so, it seemed like my work was not leading anywhere. I felt like I couldn’t just keep documenting the problem, I had to become part of the solution.

When I started being an activist on the street, the Lebanese government was actually trying to solve the solid waste problem by buying incinerators. With a complete lack of regulations and monitoring, and without any enforcement of the law on clean emissions, I felt like there was no way that the solid waste incinerators could be run in a safe way.

That’s when I decided that enough was enough, and I teamed up with a lot of activists to protest. We succeeded in raising awareness, and actually put a stop to this complete fiasco of buying incinerators to solve the solid waste problem.

The Beirut explosion of August 2020 is a crime like no other crime. First, because it destroyed a whole city, and second because the world has been watching without taking a firm stance against those who were responsible, and not pushing for justice to be served. Our government is actually protecting the warlords and those who have always stayed in power. Despite all of the sympathy that we saw from the world right after the explosion, only weeks later they forgot about it. But the people running the government are not allowing the judges to continue their work to identify the culprits. They are trying to stop the investigation at any cost.

I used to sort of teach yoga at the university. We practiced together, and I would lead some sessions. This went on for like 16 years, and then I stopped because of the pandemic. So now I practice on my own, in my spare time.

I was able to afford a car around 1990, when I first came to the US and started working in an insurance company – a white Toyota Celica GTS. It was very sporty, and it stayed with me until I finished my postdoc. My husband is a mechanical engineer, and he used to love this car. The fan that cooled the radiator was broken and we could not find a fan to replace it, so he made a line with a manual switch so that we could turn the manual switch on when we are stuck in traffic to cool the radiator. It was funny, it was like a toy for him.

I challenged myself and took my experiments to the ground, where I have to find solutions to pressing environmental problems. It is definitely keeping me up at night, because there is no room to fail. All the communities we are working with are putting high hopes in the Environment Academy team and are expecting from us to find a solution.

No comments yet