Robert P Crease and Alfred S Goldhaber

W. W. Norton & Co.

2014 | 352pp | £20

ISBN 9780393067927

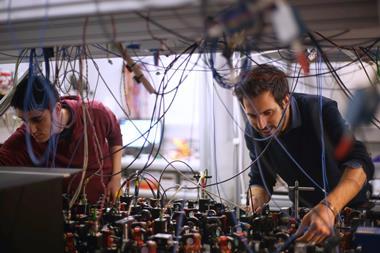

For several years, philosopher of science Robert Crease and physicist Alfred Goldhaber have taught a class at Stony Brook University, New York, US, called The quantum moment, which is open not only to physics and philosophy students but also to those studying arts and humanities. In this class about ‘the cultural impact of the quantum’ the students are asked to prepare presentations exploring that notion. These might range from experiments on quantum phenomena to songs or plays exploring the apparent implications of the theory.

The book The quantum moment explores the cultural reception of quantum physics since its earliest days, when Planck, Einstein, Bohr, Heisenberg and others grappled with the bizarre findings of their research, telling them how the world is structured.

At first, only physicists needed to confront this issue. Quantum mechanics was pronounced beyond the comprehension of the lay person, ‘like trying to tell an Eskimo what the French language is without talking French’ according to the New York Times in 1927. But during this time quantum theory first began to impinge on the public consciousness, thanks in considerable measure to Arthur Eddington’s advocacy in his 1928 popular book The nature of the physical world. And what a strange world it was. The discrete quantisation of energy and light wasn’t so hard to swallow, but Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle showed us a world rendered fuzzy, fundamentally unknowable to some degree, and arguably even lacking the causality that was science’s bedrock.

But was this so peculiar? On the contrary, in some ways quantum theory seemed to chime with the condition of modernity: a fractured and uncertain existence permeated by hidden, inscrutable connections and forces. It was a vision that artists were already exploring via cubism, surrealism and stream-of-consciousness literature. The ‘quantum moment’ fitted the zeitgeist well.

In exploring how concepts such as Heisenberg’s uncertainty, Bohr’s complementarity, Schrödinger’s cat, Einstein’s ‘spooky’ entanglement and Everett’s many worlds have been used and abused in literature, art, politics, film and humour, Crease and Goldhaber do a splendid job of illuminating the science itself. They are refreshingly open-minded about cultural appropriations – calling out ‘quantum nonsense’ where necessary but also refusing to act the grumbling pedants when artists bend and morph quantum concepts for their own purposes, which is wise. For one thing, science itself is not immune to the cultural currents in which it swims, whether that is the crisis mentality of Weimar Germany or the counter-culture of the 1960s and 70s. But also the communication of difficult ideas like quantum theory relies on finding metaphors that fit human experience: we all know about being in ‘superposition states’ of emotions or decisions, or about fantasies of parallel alternative lives. There are of course risks of misinterpretation that come with an illusion of familiarity, but that is the tightrope that all of science must walk if it wants to explain itself. These considerations make The quantum moment a valuable exposition on how to talk about science.

Purchase The quantum moment: how Planck, Bohr, Einstein, and Heisenberg taught us to love uncertainty from Amazon.co.uk

No comments yet