The final deadline set by the Chemical Weapons Convention for destroying stockpiles of chemical agents has now passed. Nina Notman reports on progress worldwide

The final deadline set by the Chemical Weapons Convention for destroying stockpiles of chemical agents has now passed. Nina Notman reports on progress worldwide

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time.

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light.

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

Wilfred Owen, 1917.

The first world war was the start of the modern era of chemical warfare, which saw many countries around the world both use – and build stockpiles of – a variety of chemicals to attack their enemies. A number of attempts have been made throughout history to ban their use, the most recent being the Chemical Weapons Convention implemented by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) based in the Hague, the Netherlands. ‘The Chemical Weapons Convention is the first multilateral treaty to comprehensively ban stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction,’ explains Grace Asirwatham, the OPCW deputy director-general.

The convention came into force in 1997, and 188 countries are now bound by it. As well as banning their use, an important part of the convention is to ensure the safe and permanent destruction of any stockpiles of chemical warfare agents. ‘The OPCW’s role is coordinating the destruction of chemical weapons stockpiles globally,’ says Asirwatham.

In accordance with the convention, the final deadline for the destruction of stockpiled chemical agents was 29 April 2012. Around 73% of the world’s declared stockpiles – a whopping 52,000 tonnes – were destroyed by this date. But four countries that are bound by the convention – the US, Russia, Libya and Iraq – were unable to meet the deadline for a combination of financial, technical and political reasons.

Over the pond

The US declared over 31,000 tonnes of stockpiled chemical weapons when it joined the convention in 1997. To date, just under 90% has been destroyed. The US agents were stored at 11 different sites, and destruction of the stockpiles at nine of these is now complete. Facilities to handle the destruction at the remaining two sites – Blue Grass, Kentucky and Pueblo, Colorado – are currently under construction.

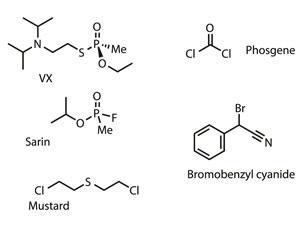

‘Blue Grass is the smallest of the two stockpiles that are left,’ explains Conrad Whyne, the executive officer of the Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives Program that is overseeing the destruction of the final two stockpiles. It contains just 523 tonnes, consisting of a combination of the nerve agents VX and sarin, as well as the blister agent mustard. The biggest problem is that it is all weaponised – meaning it is loaded into munitions. ‘There are over 101,000 munitions, consisting of projectiles and M55 rockets,’ says Whyne. ‘M55 rockets are the most hazardous munition we have because they are fully loaded with a fuse, a burster, the agent and propellant. All you have to do is give it an electric shock and it is ready to fire.’

Pueblo is an easier site to manage as it holds just mustard, contained in 780,000 munitions – and importantly no M55 rockets. But it is a much larger task, with 2600 tonnes of agent to destroy. ‘There’s a lot to do out there,’ says Whyne. Construction of the plant for this destruction – or demilitarisation – is due to be completed by the end of the year. It will then go through an extensive testing period, before destruction of the weapons begins in 2015. ‘We currently expect to have completed destruction at Pueblo by November 2019,’ he states.

‘At Blue Grass they are only about 50% complete. And we don’t expect to finish construction there until about 2017,’ he says. Again testing will follow, and destruction of the weapons is currently scheduled to start in 2020 and finish in September 2023.

Getting technical

The main reason the construction and testing of demilitarisation sites takes so long, is because destroying the munitions – and the agents inside them – is a technically challenging process. First the munitions need to be cut up, using remotely controlled robotics, to remove any fuses and explosives. ‘The warhead is then punched, drained and washed out,’ explains Whyne. The explosives and fuses go to one set of equipment for destruction, while the agent goes to the neutralisation tanks. In these tanks the agents undergo chemical hydrolysis, to break them down into other materials that then undergo a second treatment to break them down further.

Mustard can be destroyed by hot water, and so this will be used in the tanks at Pueblo. ‘Mustard is very easy, it breaks down into hydrochloric acid and thiodiglycol,’ says Whyne. The thiodiglycol, a common industrial chemical, is then treated with microbes. ‘It goes through the same stuff that would go through a sanitary sewage treatment plant,’ he explains, ‘the microbes love to eat thiodiglycol and break it down into carbon dioxide, water and salts.’

At Blue Grass, hydrolysis of the VX and sarin will require a hot sodium hydroxide solution. ‘However, when you chemically neutralise nerve agents, the bugs don’t like the byproducts,’ says Whyne. ‘We are therefore using a new [secondary destruction] method there called supercritical water oxidation.’ At very high pressure and high temperature water becomes a supersolvent, and most organic materials can dissolve in it. ‘It breaks down any organic material left over from neutralisation of the nerve agent into just carbon dioxide, water and salts.’

Russia

Meanwhile, Russia declared 40,000 tonnes of chemical weapons across seven different sites to the OPCW, and 60% of this was verified as destroyed by the April 2012 deadline. ‘Russia has finished destruction at two of their seven sites and probably in the next year there will be a third and a fourth site finished,’ says Paul Walker, the director of Green Cross International’s Environmental Security and Sustainability programme. Green Cross International is a non-government organisation set up in the mid 1990s to promote elimination of cold war chemical weapon stockpiles. Russia has stated to the OPCW that it will finish destroying its remaining stockpiles by December 2015.

Two Russian sites stored bulk agents, making them much easier to destroy than the weaponised agents held at the other five. According to Walker, these weapons are easier to handle than those in the US, owing to differences in their construction. ‘They don’t have rocket propellant or explosive in them,’ he says. ‘The Russians made their weapons like tinkertoys where you could screw on the detonator and rocket propellant and the like.’

Getting rid

The Russians have also chosen to chemically neutralise their stockpiles, explains Walker, but the method varies slightly from stockpile to stockpile. At the weaponised site of Shchuch’ye, the chemical agent is first obtained by drilling and draining, this is then broken down using chemical hydrolysis. The breakdown products are then incorporated into bitumen, placed in drums and stored permanently on the site.

The Russian demilitarisation process has been heavily supported internationally – both financially and practically. The construction of the demilitarisation plant at Shchuch’ye – a site in a remote area approximately 1600km east of Moscow – in particular has received significant foreign assistance; while the US has contributed $1 billion (£645 million), much of the other international support has been coordinated by the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD). Shchuch’ye held 5400 tonnes of agent in 1.9 million munitions, an MOD official responsible for the programme of assistance to Russia tells Chemistry World. This site was selected for UK support because ‘some [of the munitions] were readily portable and therefore a potential proliferation risk’, he explains. ‘The UK has implemented procurement and construction projects worth over £90 million at Shchuch’ye. Some £24 million of this funding was contributed by the UK, £50 million by Canada, and the balance by 11 other international donors.’

And while construction of the site is not yet complete, destruction started there in March 2009. ‘Around 3000 tonnes of nerve agent in 1.2 million munitions has now been destroyed,’ says the MOD official.

Libya and Iraq

When Libya joined the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2004, it declared 24.7 tonnes of bulk mustard to the OPCW. Destruction began in October 2011, and just under 54% of their declared stockpile was verified as destroyed before the programme was halted in February 2011, owing to the outbreak of civil war.

In November 2011, previously undisclosed chemical weapons – discovered after the fall of the Gadaffi regime – were also declared to the OPCW. The ‘new’ stockpile is militarised, whereas the two previously declared held only bulk agent, explains Walker. ‘There is probably still some stuff they haven’t declared,’ he adds. ‘Not because they don’t want to, but because [the current government] probably doesn’t know [it exists].’ Libya is also now working towards a final destruction deadline of December 2015.

Iraq is the only country signed up to the convention that wasn’t working towards the 29 April 2012 deadline. This is because it didn’t join the agreement until spring 2009, explains Walker. And its destruction programme is still very much in the planning stage.

‘Iraq will be a very interesting case,’ says Walker. On joining the convention, it declared two large bunkers that were filled with chemical weapons and related materials. ‘This, in the end, could be the most complicated demilitarisation of all, because the bunkers have been hit by aerial bombs. There are open chemical agents all over the floor. And these are big warehouses too – three storeys the size of a soccer field.’

Iraq is also receiving significant international support with its demilitarisation efforts. ‘The UK has offered to provide training assistance to Iraq to support its chemical weapons destruction programme. This comprises medical and analytical training and is expected to be delivered later this year,’ says the MOD representative. ‘The UK has also offered to provide technical advice to Libya,’ he adds.

Although the Chemical Weapons Convention’s final deadline has been missed by a handful of the countries, the mood during a meeting of the world demilitarisation experts in May – the 15th International Chemical Weapons Demilitarisation Conference held in Glasgow – was extremely upbeat. ‘The programmes have gone relatively well; they have accomplished a lot,’ says Walker. ‘Three quarters of the world’s chemical weapon stockpiles have gone.’ And everybody seemed hopeful that it won’t be long until the world is finally free of the chemical legacy of past wars.

Old chemical weapons and the UK

The UK didn’t have any stockpiles of active chemical weapons by the time the Chemical Weapons Convention came into force, as it disposed of all its supplies shortly after the second world war – either by dumping them at sea or burying them in pits on Ministry of Defence (MOD) owned land. These were both acceptable disposal methods at the time, explains Mark Rogers, a munitions disposal and toxic operations manager at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) in Porton Down, UK.

What the UK did have at the time the convention was ratified, however, was approximately 3000 old chemical weapons – ones that have deteriorated to such an extent that they can no longer be used. The convention dictates that these must also be disposed of in a safe and permanent manner. Speaking to Chemistry World at the 15th International Chemical Weapons Demilitarisation Conference held in Glasgow in May, Rogers explained that: ‘These were legacy weapons that we’ve had either in storage somewhere or have been recovered from a burial pit.’

The sole destruction facility for old chemical weapons in the UK is based at Porton Down, near Salisbury. ‘Any weapons found anywhere on mainland UK will come to Porton Down for destruction,’ says Rogers. This facility was set up to destroy old chemical weapons after the convention came into force and remains active today, as there are still occasional finds of old chemical munitions. ‘These ad hoc finds are primarily at old MOD sites that are being redeveloped,’ he explains.

Going up in smoke

Owing to the small numbers of munitions involved, the facilities are far smaller and more personalised than those used at the US and Russian stockpile sites, explains Rogers. Each munition will go through a series of screens to obtain vital information about its makeup. ‘Every round that comes in is treated as an individual round,’ he says. This is because there were a number of different types of munitions made in the UK and also because they can be fragile, rusty or decaying, due to age and burial conditions.

‘We use screening techniques like x-ray to ascertain what’s inside it – whether it’s a liquid or a solid – and to see details of the fuses and details of configuration regarding explosives or expulsion charges,’ says Rogers. X-ray will also allow them to estimate the quantity of agent. ‘Then we use neutron activation analysis to ascertain what the chemical content is. There are three types of agent we come across in the UK: mustard – the most common one, bromobenzyl cyanide and phosgene.’

After accessing the agent using remote drilling and cutting equipment, the mustard and bromobenzyl cyanide are destroyed by incineration. Phosgene – a volatile gas at atmospheric pressure – is destroyed using hot water chemical hydrolysis.

Nina Notman is a science writer based in Salisbury, UK

No comments yet