A technique that uses radiocarbon dating to pinpoint when an artwork was created could make it easier to detect forgeries.

Conservation scientists performed the new analysis on a known counterfeit painting created by the forger Robert Trotter. The painting Village Scene with Horse and Honn & Company Factory is signed Sarah Honn and dated 1866, but measurements of the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12 in an organic component of the paint shows it can’t have been created until the late 20th century.

‘If other techniques don’t find proof of a forgery, that’s where radiocarbon can maybe help,’ says Laura Hendriks from ETH Zurich in Switzerland, one of the researchers who carried out the work. She adds that the approach could be particularly effective at revealing fakes created after 1950 because materials can be dated very precisely.

‘During the nuclear bomb tests after the 1950s the carbon-14 concentration in the atmosphere doubled, and that’s a very specific marker that we can use,’ she says. ‘If any forgery was made in that time period and it claims to be a da Vinci or a Raphael we can really easily say that’s not true.’

It hasn’t been possible to use radiocarbon dating on works of art before now because it previously required large samples of material – it’s just too risky to remove grams or even milligrams of paint from a potentially genuine artwork because of the damage this could cause.

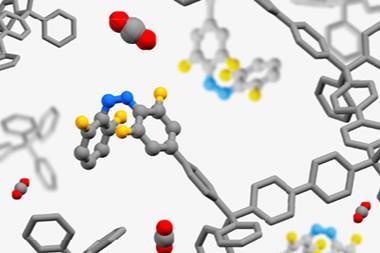

But recent technological advances mean only miniscule samples are required. Hendriks and colleagues used an elemental analyser, which burns a sample to convert it into carbon dioxide gas, coupled with an accelerated mass spectrometer (AMS). This setup can work with very small amounts of material, and the team was able to take measurements using a single thread from the canvas, and a tiny paint chip weighing less than 200µg.

First, they used standard non-destructive techniques to find a suitable sample they could take from an existing crack in the painting. ‘The white paint we took only carried inorganic pigments, which was actually ideal because then we could specifically target the binder material without any interference from other carbon sources,’ explains Hendriks.

Once they had the samples of paint and canvas they burnt them to get carbon dioxide, which was trapped and fed into the AMS to measure the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12. They took care to clean the samples and make sure they were free of any contaminants, such as varnish added during later renovations, which could skew the readings.

The analysis showed the canvas could have been made at any time from the late 17th to mid-20th century, which includes the date of 1866 given to the painting. However, the binder in the paint had a high proportion of carbon-14 that showed it came from oil that was harvested from seeds after the 1950s ‘bomb peak’, either in the date range 1958–1961 or 1983–1989. In this case, the researchers conclude, Trotter appears to have used an old canvas to make the forgery appear more legitimate.

They say this shows how radiocarbon dating can help shed light on complex cases. Hendriks emphasises, however, that it should be used to complement rather than replace existing techniques.

Jilleen Nadolny, a principal investigator at the company Art Analysis & Research, has experience using radiocarbon dating and agrees it is best used in combination with other analytical tools. ‘It’s a great dating technique, but it has lots of limitations,’ she says. ‘You have to be very aware when sampling to avoid contamination, and there are huge chunks of time where you don’t get anything specific.’ She adds that Hendriks and colleagues have managed to make some important improvements.

‘The work they’ve done is really impressive with making the sample size smaller and doing better work with cleaning, because restoration often contaminates the sample we’re looking at.’

‘It’s a really nice example showing all the things you have to think around. Forgers very commonly use old canvases, for instance. So knowing the history and the context around the objects is extremely important.’

References

L Hendriks et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2019, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1901540116

No comments yet