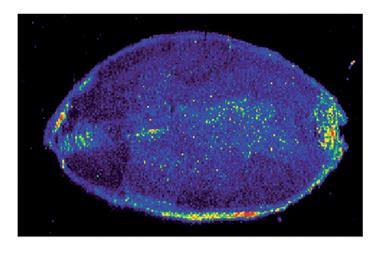

Analysis of a degraded wall painting at Herculaneum may help conservators clean and restore it

Conservation scientists using x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) have revealed different layers of colour and an underlying sketch beneath a 2000-year old wall painting of a woman’s face in the ancient Roman city of Herculaneum.

Since being excavated in the mid-19th century the portrait – found in the ‘Casa dell’Atrio a Mosaico’ building – had deteriorated because of exposure to air and moisture, and a lot of the fine facial features are no longer visible.

‘X-rays penetrate through the layers so you can see underlayers,’ said Eleonora Del Federico from the Pratt Institute in New York, US, speaking to delegates at the 254th American Chemical Society National Meeting and Exposition in Washington, DC. ‘Now we can look at lost paintings and find out about how the artists worked.’

As part of the Herculaneum Conservation Project, Del Federico and colleagues used a portable x-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanner to analyse the fresco on site. The technique works by firing a beam of high-energy x-rays at the painting, which are absorbed and then re-emitted at characteristic wavelengths by different elements. The presence of these elements can then be mapped to show where different pigments are used.

The map of iron, for example, revealed the original sketch underlying the painting, which had been done using an iron-based pigment, most likely yellow ochre. Maps of aluminium, silicon, potassium, copper and lead also showed how different pigments were used by the artist to shade and highlight different areas of the face, revealing details that are not visible with the painting in its current state.

‘We can see the use of pigments, we can see shading and contouring,’ said Del Federico. She explained that a lead-based pigment, possibly read lead, was used ‘like eyeliner’ to frame the eyes, and to highlight the mouth and nose. Areas of potassium and silicon on the cheeks suggest that the pigments green earth (glauconite) and Egyptian blue may have been used to create a skin coloured paint.

There are clearly some very complex things going on. Painting her was quite a challenge.

In addition, overall low concentrations of calcium indicate the painting was a ‘secco’ fresco, where pigments are mixed with an organic adhesive before being painted onto a layer of wet lime mortar (calcium hydroxide) on the wall.

‘We can’t say as much as we would like about the painting technique,’ said Del Federico, who stressed that it is impossible to tell from just the elemental maps exactly which pigments were used. ‘But there’s clearly some very complex things going on … painting her was quite a challenge.’

As well as providing insights into how the art was created, and what it may have originally looked like, Del Federico hopes that their findings could help conservators choose the most appropriate materials for cleaning and restoration.

‘This work shows the impact of what XRF can do onsite,’ she concluded. ‘It is becoming a very powerful technique.’

No comments yet