Watchdog faults US Environmental Protection Agency for lax oversight of experiments involving asbestos

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) internal watchdog has found that the agency’s costly and time-consuming experiments on alternative asbestos control methods (AACM) lacked effective oversight and threatened human health.

In a recent report, EPA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) concluded that the agency didn’t conduct the research under a controlled process to ensure oversight. It also said EPA had disregarded research guidance designed to safeguard research quality, and inappropriately agreed not to enforce environmental laws during the research.

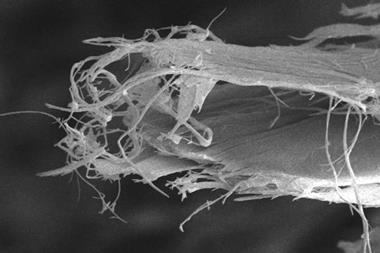

Asbestos is a human carcinogen with no known risk-free level of exposure, and contact with it can lead to serious diseases such as lung cancer and mesothelioma. The city of Fort Worth in Texas had proposed an alternative method to demolish asbestos-containing buildings in 1999. The EPA Office of Research and Development’s National Risk Management Research Laboratory (NRMRL) took over the effort in 2003, and assumed responsibility for the related research.

The agency’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance enabled the experiments by granting so-called ‘enforcement discretion,’ which excused certain violations of environmental laws during testing. The OIG said this action eliminated ‘critical internal controls’ in the research process.

Wasted resources

EPA conducted the research in question from 1999 until the project was terminated in 2011 due to technical deficiencies. It spent almost $2.3 million (£1.42 million) in contractor costs and expenses between 2004 and 2012, and $1.2 million in research staff time on the experiments between 2005 and 2012.

‘The high dollar cost, potential public health risks, and failure…to provide reliable data and results are management control problems that need to be addressed,’ the OIG concluded. The office said that the work went on for over a decade without an agreed research goal, which wasted resources and potentially exposed workers and the public to unsafe levels of asbestos.

Specifically, the OIG found that the experimental design for the research did not adequately address health and safety issues for workers and the public, or consider potential environmental impacts. For example, the report points to unresolved questions related to the level of worker respiratory protection, and the addition of weight to a building in imminent danger of collapse.

For its part, EPA says it concurs with the OIG’s findings and that the alternative asbestos control method in question remains unapproved and won’t be used under the agency’s National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants.

In addition, EPA says it has made significant changes to its research planning process, and has taken numerous steps to ensure the safety and health of employees and contractors, including updating health and safety procedures and training.

Lack of monitoring

The agency has also come under fire recently for failing to regulate pollutants entering water supplies. In a separate report, the OIG said EPA needed to do more to prevent hundreds of hazardous chemicals from contaminating waterways.

It pointed out that EPA uses the Clean Water Act to regulate only 126 toxic chemicals that could flow to sewage plants, leaving about 300 chemicals that are considered hazardous under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

‘Sewage treatment plant staff do not monitor for hazardous chemicals discharged by industrial users,’ the report said. The OIG blamed this on a general regulatory focus on a priority pollutants list that hasn’t been updated since 1981, as well as limited monitoring requirements and a lack of knowledge of discharges reported by industrial users under the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), among other things.

The office recommended that EPA develop a format for sharing annual TRI data, develop a list of chemicals beyond the priority pollutants list for inclusion in permits, confirm compliance with the hazardous waste notification requirements, and track required submittals of toxicity tests and violations.

No comments yet