Research links Parkinson’s disease to an enzyme that affects the functioning of mitochondria

A new avenue for treating Parkinson’s disease could be opened up by research linking the role of a particular gene with this neurodegenerative condition. Teymuras Kurzchalia and Anthony Hyman of the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Germany, and their coworkers say that the degeneration of neurons may be caused by the malfunction of the enzyme encoded by a gene called DJ-1, which normally helps protect cell mitochondria from stress. Their studies suggest that administering the enzyme’s products as a dietary supplement might redress the deficiency.

Vulnerability to Parkinon’s, which impairs muscle control and movement, has been known to be increased by mutations to the DJ-1 gene, as well as several other genes. ‘DJ-1 has been the focus of molecular study in Parkinson disease for long time, although its biochemical function has been unknown,’ says Chankyu Park, a biologist at the Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology who has studied the issue. The gene product of DJ-1 is a glycoxalase enzyme, which converts glyoxal and methylglyoxal into glycolic and lactic acids. But why this causes death of neurons in the brain has not been clear.

Now Kurzchalia and colleagues have found a reason for the link. Their suspicions about the role of DJ-1 were aroused when they found that larvae of the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans responded to the stress of being dried out by increasing production of the DJ-1 enzyme. It has been suspected for some time that DJ-1 protects mitochondria, and the team’s studies showed that it does this by maintaining the electrochemical potential across the mitochondrial membrane, which is essential for energy production.

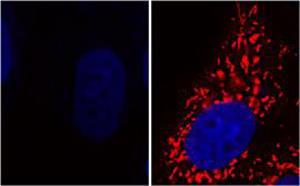

To test this further, they turned to the more easily manipulated HeLa strain of human cells. They found that suppressing DJ-1 protein production decreased the mitochondrial potential, as did exposing the cells to paraquat, a weedkiller implicated in the onset of Parkinson’s. But in both cases, administering the products of the DJ-1 enzyme (glycolic and D-lactic acid) restored the membrane potential. These compounds could also rescue HeLa cells impaired by the suppression of another Parkinson’s-related gene, PINK1.

Might treatment therefore simply be a matter of increasing the intake of these acids, which are natural products found in some foods such as prunes and yoghurt? Kurzchalia is cautious about that. ‘The way from a basic discovery to a therapy is very long,’ he warns, ‘and only in collaboration with medical doctors can one design therapeutic approaches.’ However, this approach is very different from the usual strategy of treating Parkinson’s with dopamine, the neurotransmitter produced by affected neurons.

‘The novel function of the DJ-1 glyoxalase will certainly lead to a new therapeutic approach for Parkinson’s disease,’ says Park. But he says that there remains a big question about the chirality of the lactic acid: while Kurzchalia and colleagues find that only D-lactic acid restores proper mitochondrial function, Park’s latest work seems to show that the DJ-1 protein produces specifically L-lactic acid. So further studies are needed to figure out exactly what is going on.

No comments yet