Bayer has failed in its attempt to stop Indian regulators approving a copy-cat version of one of its patented drugs

Bayer has failed in its attempt to stop Indian regulators giving marketing authorisation to a generic version of its kidney cancer drug Nexavar (sorafenib), despite its 20 year patent having only been granted last year.

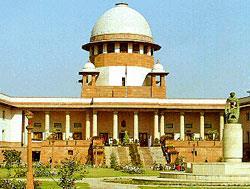

In November 2008, Bayer won a case in the Delhi High Court which prevented the Drug Controller General of India (DGCI), from giving Indian generics manufacturer Cipla marketing authorisation for the drug after Bayer complained this would infringe its patent. Cipla returned to the court to challenge the ruling, and this time the judge ruled in its favour, awarding costs of Rs675,000 (?8,400) against the German company, accusing it of trying to ’tweak public policies through court mandated regimes’. Bayer is expected to appeal against the ruling.

At the heart of the issue is the fact that in India, as is the case in the UK, there is no link between the granting of a marketing authorisation and the intellectual property (IP) situation - any IP issues are dealt with separately.

The situation in the US is very different - a generic company has to prove that any existing patents on a drug are invalid, or that they are not being infringed, before the FDA will grant a licence. Bayer wanted the Indian courts to consider the two issues to be linked, as is the case in the US.

Cipla has also challenged Bayer’s patent on the drug, a case which Bayer has said it will defend ’vigorously’. If Cipla’s challenge fails, it will still be able to sell generic sorafenib, but will be laying itself open to being liable for damages, and Bayer would be able to apply for an injunction to stop the sales.

’The situation may not be as bad as it sounds for Bayer,’ says Adam Cooke, partner in IP at law firm Lovells. ’The litigation seems to be simply about whether or not a marketing authorisation would be granted for the generic product. What Bayer was seeking to do, it seems, is to get the regulator to consider the patent position when deciding whether to grant a marketing authorisation. It was challenging whether it was appropriate for the marketing authorisation to be granted on the basis that it has patents, and because the generic company was infringing its patents it would be a waste of time.’

According to Tapan Ray, director general of the Organisation of Pharmaceutical Producers of India, some experts feel the ruling may encourage generics companies to launch their own versions of patented drugs in India, despite the risk of paying damages if they are later shown to have infringed patents. ’The status of the grant of patent should be reviewed, through [an] appropriate drug regulatory mechanism, before granting marketing permission to generic formulations,’ he says. ’If the innovative product is already patented in India, marketing permission for the generic formulation should be withheld.’

This case may have implications for other companies trying to stop generic versions of their on-patent drugs being licensed in India. Bristol-Myers Squibb is engaged in a similar case against generic company Hetero Drugs over its patented chronic myeloid leukaemia treatment Sprycel (dasatinib). In December, the Delhi High Court ruled that DGCI could not grant Hetero marketing authorisation for a generic, but in the light of the Bayer/Cipla decision, this may well be overturned.

Sarah Houlton

No comments yet