New report highlights rapid growth in designer drugs fuelling fears that they could cause many deaths

New designer drugs are popping up in Europe at an unprecedented rate, sometimes on the illicit drug market and sometimes as ‘legal’ alternatives to controlled drugs, according to the latest report by the EU drugs agency (EMCDDA). These substances are often taken by thrill seekers despite the fact that very little is known about their safety.

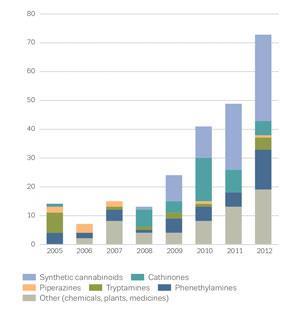

In 2012, the EU Early Warning System (EWS) was alerted to 73 new psychoactive substances (NPSs) compared with 49 in 2011, 41 in 2010 and 24 in 2009. Some of these substances will find their way onto the market, packaged as ‘legal high’ products in shops and online.

My fear is that as the drugmakers delve deeper into the databases of compounds, one will pop-up with disastrous side-effects

‘The trend has been unremittingly upward for about eight years,’ says Ric Treble, scientific adviser at LGC in Teddington, UK, who is involved in identifying legal highs. ‘Novel materials are appearing at an ever-increasing rate and this is likely to continue. It’s an international problem.’

This proliferation has happened suddenly, observes David Nichols, emeritus professor of pharmacology at Purdue University, US, but it may be a temporary spike. ‘Drugmakers trawl through the literature for interesting compounds they can make and play around with, but there are only a finite number of compounds. It’s possible there may not be a whole lot more.’

Potent substitutions

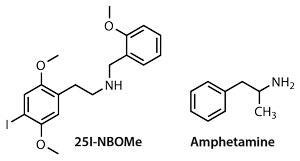

Of the 73 NPSs in 2012, 14 were new substituted phenethylamines, the group that includes amphetamine and ‘ecstasy’, the highest number reported since 2005. Simon Brandt of Liverpool John Moores University, UK, is a co-ordinator for the UK’s EWS on NPSs. ‘It was thought that potency would drop noticeably once the primary amine on the side-chain was extended beyond N-methyl or N-ethyl. However, in recent years it has become apparent that some of the bulkier N-benzyl substituents, for example 2-methoxyphenyl, show increased potency. These ‘NBOMe analogues’ appear to have psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects below 1mg, which is more potent than most phenethylamines and amphetamines.’

However, the largest group of reported NPSs were synthetic cannabinoids. Numbers are growing: nine were reported in 2009, 11 in 2010, 23 in 2011 and 30 in 2012. As of May 2013, the EMCDDA had been notified of 84.

Synthetic cannabinoids are chemically diverse, but they all bind to the cannabinoid receptors, mimicking the effects of the main active ingredient in cannabis, ?9- tetrahydrocannabinol.

Mining the literature

Producers of NPSs have three sources of information, says Brandt: potentially active compounds abandoned by the pharmaceutical industry in previous decades, perhaps due to unfavourable properties; medicinal products with withdrawn marketing authorisations; and the research literature, which describes the development of many potentially psychoactive substances as receptor probes. ‘It has become evident in the last five years or so that many of these substances [from the literature] have been manufactured on a large scale and sold as NPSs,’ he says.

The power of the internet has fuelled the ‘sea-change’ in emerging NPSs, says Treble. ‘It allows access to, and communication of, all kinds of data. A compound rejected for being too strong a stimulant or producing hallucinogenic effects is promising material.’

The older literature is a focus of attention, agrees Nichols, who knows his work studying how compounds interact with the brain has been mined for new legal highs. His shock and feeling of responsibility – people died in the Netherlands after taking tablets containing a compound named in one of his publications – has been gradually overtaken by concern. ‘My fear is that as the drugmakers delve deeper into the databases of compounds, one will pop-up with disastrous side-effects. We’ve probably not seen the most dangerous one yet.’

Little is known about the toxicity and detailed pharmacological properties of many of these substances, says Brandt. The report notes that researchers have concluded that ‘legal highs’ containing synthetic cannabinoids, for example, are potentially more harmful than cannabis. Adverse effects include agitation, seizures, hypertension and vomiting. They may be associated with psychiatric symptoms and kidney damage.

Some compounds are particularly potent, says Simon Hudson of HFL Sport Science, a drug surveillance lab, such as the designer phenethylamines 25I-NBOMe and 25B-NBOMe, and the synthetic cannabinoid AM2201. ‘The first two are supplied like LSD as a few hundred micrograms on a piece of paper.’

Producing a high

Manufacturing NPSs is relatively simple. ‘Pharmaceutical drugs require between five and 12 steps to synthesise, whereas these need only two to three,’ explains Nichols. Treble agrees: ‘The chemical manufacturers, typically in China, can pretty much make anything you want – with no questions asked. These molecules are relatively small so they are relatively easy to make. Any competent synthetic chemist can follow the recipe.’

Once in Europe, the bulk synthetic chemicals, typically only a few milligrams, are mixed with or sprayed onto herbal bases. Liquid solvents, such as acetone or methanol, dissolve the powders. Once mixed the herbs are then dried and packaged.

In a bid to turn the tide, governments test internet purchases and seizures, and report findings to international coordinating agencies, so that controls can follow. In the UK, over 200 synthetic cannabinoids are now illegal through a single generic definition. But as Treble points out: ‘No sooner has an NPSs been controlled, a new one will appear on the market. Legislation is driving development of new materials.’

New Zealand leads the way

In a world first, the New Zealand government is trying to regulate, rather than criminalise, the legal highs’ market. It will force drug manufacturers to prove their products are low-risk before they can go on sale. The Psychoactive Substances Bill, expected to become law by August, is being closely watched by the EMCDDA and other agencies around the world.

The bill defines a psychoactive substance as anything whose primary purpose is to induce a psychoactive effect and is not already covered by other legislation. The bill will require drugmakers to pay for clinical trials.

This could create the world’s first legal, regulated market for recreational drugs. If a drug passes the clinical tests, it can be legally sold. However, an expert committee will define ‘low risk’ so it is possible that very few drugs will pass muster.

No comments yet