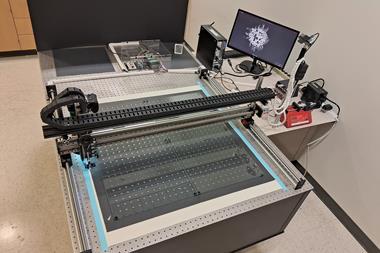

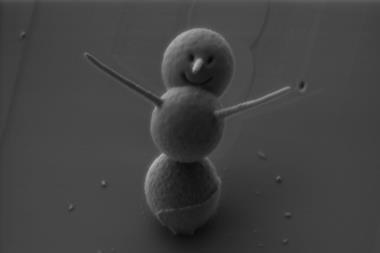

Have you heard of the 24 Hours of Le Mans? The gruelling day-long endurance race held every year in France? A few hundred kilometres away in Toulouse, scientists are gearing up for an even longer, totally unprecedented race. It won’t take place on a classic track, but on the world’s smallest purpose built gold racing circuit. It’s the first ever nanocar race or, simply, nanorace. Fun as it may seem, the race has a serious scientific purpose: testing a unique scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) recently installed in the south of France. The race will also provide new insights into how nanocars cope in extreme conditions.

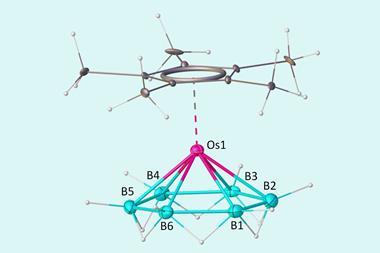

Christian Joachim, a researcher at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and organiser of the nanorace, says that ‘thanks to the progress on STM systems, it’s now possible to manipulate single atoms, or even molecules’. ‘With the new four tip microscope, different people can work on the same surface simultaneously. This technique will ultimately increase the operational speed of an otherwise slow instrument,’ he adds. This means that four nanocars can be ‘driven’ independently, with each tip powering a machine. The electrons flowing from each tip will in effect be the nanocar’s fuel – propelling it along – and the winning machine will be the one that travels the furthest.

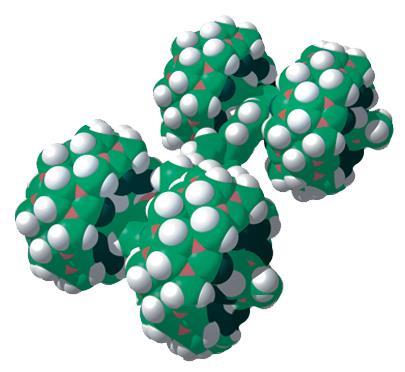

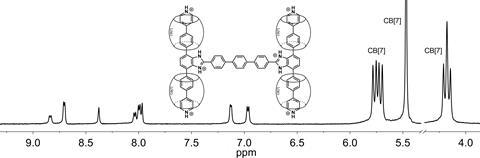

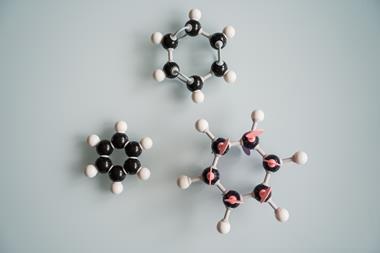

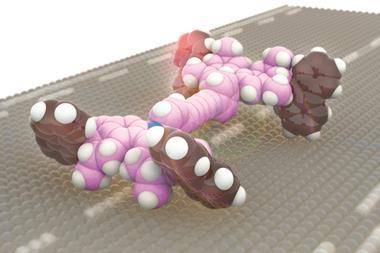

Around a month ago, three of the six participating teams took part in a ‘warm-up’ lap in Toulouse. Éric Masson, one of the team leaders of the American Ohio Bobcat Nano-Wagon team and a researcher at the University of Ohio in the US, is excited about ‘getting to use this pretty amazing four tip STM’. He had never worked in nanocars before, but had synthesised other supramolecules. He decided to combine some of those and design a nanocar for the first time. ‘Our design merges aesthetics and practicality. I had previously worked on macrocycles that could easily be envisioned as the wheels, and pseudorotaxanes with a rigid axle component.’ The Ohio team built its nanocar in an elegant manner: ‘We suspend the frame in water,’ explains Masson. ‘Then, we add the wheels, and the car self-assembles step by step. When we add the last wheel, the car suddenly becomes water soluble, and the precipitate disappears.’ The complexity of the nanocar’s structure suggests that it would have a highly complex NMR spectrum. But Masson says this isn’t the case at all and, thanks to the symmetry of the nanocar, ‘the NMR is pristine, there’s no doubt on where the wheels end up’.

Race to the bottom

Waka Nakanishi, team leader and designer of the Japanese NIMS–NAMA team and researcher at the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan, says that ‘the objective of the race is to see how molecules behave under these very particular conditions’. ‘We’re having this race to have fun and to share [the importance of our] discoveries with the world,’ she adds. The main challenge for her team is to get the nanocars onto the gold track and eventually image them with the STM microscope. She remains optimistic, ‘as there are millions of cars; if one of them is destroyed we can always use a different one [and continue the race],’ Nakanishi says.

We-Hyo Soe, one of the ‘drivers’ for the Japanese team and the holder of the 2012 Guinness World Record for the world’s smallest working gear, explains to Chemistry World why the race will take 38 hours. ‘Because we have to keep the track at cryogenic temperatures of around 5K (–268°C), we are limited by the capacity of our helium tank.’ For Soe, ‘winning the race is not important’ as it’s all about expanding understanding of the behaviour of molecular machines.

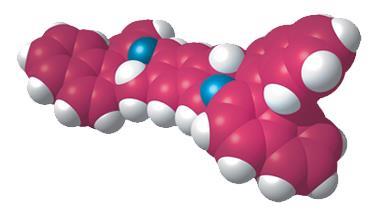

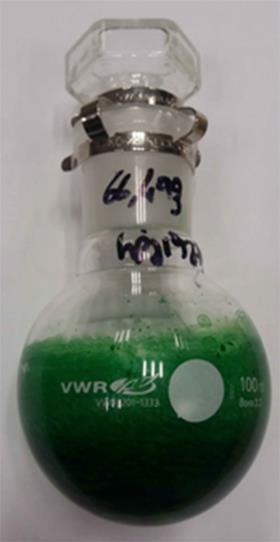

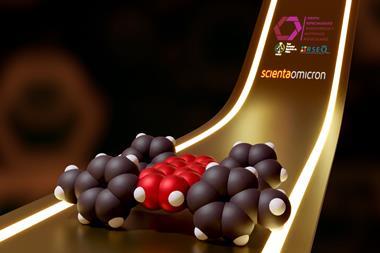

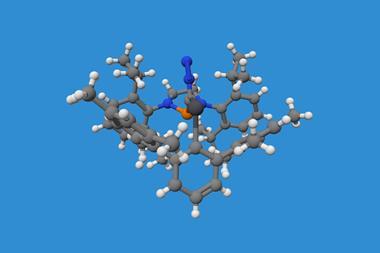

However, Gwénaël Rapenne, leader of the French Toulouse Nanomobile Club team and chemistry professor at the University of Toulouse , says: ‘The goal of this race is to win! Kidding apart, the real goal is to use the new four tip STM microscope, which is quite unique in the world.’ Rapenne also sees the nanorace as a wonderful opportunity to find new sources of funding. ‘We cannot use public money to finance events like the race, and it’s also complicated to get private companies to fund fundamental research, because applications are too far away.’ The nanorace has been sponsored by companies like Toyota, Peugeot or Michelin. Rapenne says that support from the car companies will help them to develop their new STM microscope. The French team features two cars: their original, techno-mimetic, covalently-bonded nanocar and their newly designed curved nanocar – dubbed ‘the green buggy’ as the molecule is actually green – which minimises interactions with the track. Rapenne says that ‘molecular assemblies with covalent bonds are much more stable, rigid and accurate than the self-assembled nanocars’. According to Rapenne, ‘similar molecules can last up to six months within the STM. They are insanely stable!’

Dream machines

Despite some rivalry, all the team leaders agree that the race will benefit their field. Many are also over the moon that the 2016 Nobel prize in chemistry went to a topic close to their hearts– molecular machines. ‘I am very happy for my PhD supervisor, Jean-Pierre Sauvage,’ says Rapenne. ‘Until now, a lot of people thought molecular machines were just fun to play with with no real-world applications. The Nobel prize recognises the true importance of the field,’ he adds. ‘It will certainly boost research in molecular machines,’ agrees Soe.

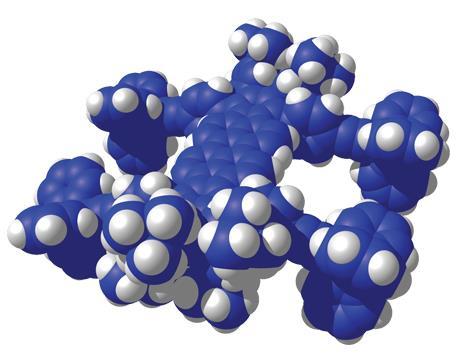

Steve Goldup, who works on interlocked molecules and molecular machines at the University of Southampton, UK, says ‘perhaps this nanorace catches the imagination in a way the Nobel prize doesn’t, because it’s a very simple idea: people made really tiny cars and they’re going to race them. Everyone gets that.’ Goldup says it is thought-provoking that ‘some of the structures aren’t recognisably cars in the sense that they don’t have four wheels, a chassis and a motor’. ‘We know how to move things on the macroscopic scale; what will work best at the nanoscale, on a gold surface?,’ he wonders. He adds that the four tip STM is the real star of the show. ‘These kinds of imaging techniques will be useful not only in nanotechnology, but also in biological applications, and it’s a great idea to challenge the system to be fast’.

Goldup adds that ‘it would be quite cool to have a betting option on the website’, and has his favourite. ‘My money would go on the Swiss team, because the design is so simple, and a bit counterintuitive,’ he says. ‘The German nano-windmill is also pretty nice.’

Masson says the race is set to place on 27–29 April next year. After two qualifying rounds, four teams will make it to the final 38-hour race. ‘Each image takes around five minutes to get, and the nanocar only moves in tiny 3nm steps,’ explains Joachim. There will almost certainly be pit stops for drivers to swap, and the organising committee has also laid on somewhere for the drivers to get their heads down. ‘But in case they want to stay awake the manufacturer of the microscope offered us a free coffee maker!,’ Joachim jokes.

Updated 13 Dec to clarify the location of Le Mans.

No comments yet