A shortage of key chemicals needed for tests to diagnose Covid-19 has hampered screening efforts, but now researchers in the US have developed a new test that doesn’t rely on these scarce reagents.

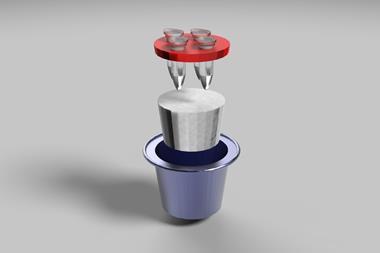

The standard PCR test has three steps – first, a sample swab is placed into a vial containing a medium that the virus migrates into. Reagents are then used to extract the viral DNA and finally any viral genetic material is amplified and then detected using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). A team at the University of Vermont and University of Washington partnered to create a method to test for Sars-CoV-2 – the virus that causes Covid-19 – that skips the second extraction step in RT-PCR tests. ‘A lot of places here in the US can get access to these separation reagents for this second step, but many cannot, and if you spread out into other countries it’s an even bigger problem,’ says Jason Botten, an immunologist at the University of Vermont who co-authored the study.

The researchers evaluated the accuracy of the new test using 215 samples from Covid-19 patients and 30 controls, and found that it correctly identified 92% of the positive ones and 100% of the negative ones. Furthermore, those positive samples that the new test failed to catch were shown to contain very low levels of the virus.

‘We were the first research group to put out a report on this working in a preprint,’ recalls Botten. The team’s preliminary results in a bioRxiv preprint in March showed that their two-step test accurately identified six positive and three negative Covid-19 samples. ‘Within two or three weeks, other labs started announcing in other preprints that they had tried this and it was looking promising,’ Botten adds.

He notes, however, that the trade-off for removing the extraction step is a less sensitive Covid-19 test. Tests for Sars-CoV-2 rely on multiple cycles of amplification to produce a detectable amount of RNA for diagnosis. The traditional PCR test runs 40 cycles, while this new two-step version only runs 32 cycles, Botten explains.

‘But we think it is an okay trade-off because more and more experts are realising that right now we need tests that pick up people who are infectious, not just those who are positive for viral DNA,’ he says. ‘This test picks up those with low levels of the virus who are getting ready to clear it.’

After the March preprint made a big splash, the researchers heard from people at labs around the world who wanted to learn more. The two-step test was of particular interest to the head of the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) – a non-profit based in Washington DC that aims to engage scientists from academia, government and industry to address global environmental health issues.

Now, through a new HESI programme, 10 labs in seven countries – Brazil, Chile, Malawi, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, the US and France – have agreed to give their test a trial run. Under the initiative, each of these participating labs will test the novel diagnostic on a series of positive and negative Covid-19 samples to see if they can replicate the findings. The results so far have been ‘really, really great’, Botten tells Chemistry World. With all the data generated, the researchers intend to seek emergency use approval for the test from the US Food and Drug Administration.

No comments yet