A ‘review mill’ that appears to have produced at least 85 similar peer-review reports featuring coercive citation could be an indicator of a new organised form of academic malpractice. The review reports were discovered alongside articles published across several journals run by the open-access publisher, MDPI, and were brought to light by a volunteer-led investigation posted online by Predatory Reports – an organisation that aims to highlight unethical publishing practices.

The work was carried out by María de los Ángeles Oviedo García, a professor of business management and marketing at the University of Seville, Spain, who started investigating after reading a suspect review report published alongside an article in MDPI’s Journal of Clinical Medicine. The report stated that the authors ‘should cite recently published articles such as …’ and then provided two digital object identifiers (DOIs) corresponding to articles that the reviewer themselves had co-authored.

‘[I thought] why is this sentence so clear to introduce these two articles in the introduction section?’ Oviedo García explains. ‘Something rang a bell in my head and I thought, I’m going to check it and then I found more and more articles using the same sentence structure. I kept thinking about it and thought there must be something there.’

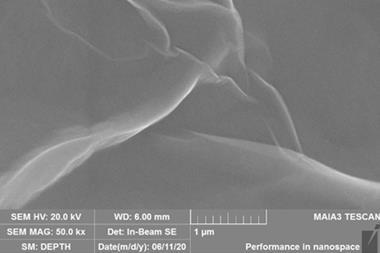

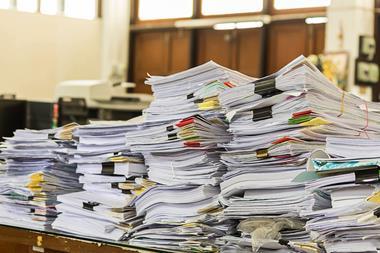

Oviedo García’s detective work was made possible because of the emerging practice of transparent or open peer review, in which peer-review reports and the reviewers’ identities are made publicly available when a scholarly article is published. In total, she discovered a set of 85 review reports across 23 MDPI journals published between August 2022 and October 2023 that were very similar in content, contained similar typos, and most of which included coercive citation – the practice whereby reviewers ask authors to cite their own work to boost their citation counts. A large proportion of the affected papers focus on chemistry and related subject areas.

‘It was so obvious, so evident,’ Oviedo García recalls. ‘The structure was very similar and the content of the review was very similar … the further I dug, the more strange things I was finding – why did no one realise the high rate of self-citation?’

‘I thought: “My goodness, this needs to be exposed – this is clearly fraud in the review process,”’ she adds. ‘It is not a proper review if you repeat exactly the same, for every type of paper, in every type of journal, 85 times.’

She started by sharing her findings on X, formerly Twitter, sharing 10 articles that appeared to have been affected by the review mill every weekend.

‘Someone [on X] asked me if it could be related to fake reviewers – which means there is no person behind that profile or a person having fake profiles in the system,’ says Oviedo García. ‘So I went to Scopus and I found that all [10] of the reviewers had worked together sometime in the past. I could also count how many reviews they had performed for MDPI journals – it’s a huge amount.’

Responding to the findings, a spokesperson for MDPI told Chemistry World that the organisation was aware of the situation and was conducting an inquiry. ‘It should also be noted that such inquiries do require a certain amount of time; nevertheless, we remain prepared to provide updates once our inquiry has been concluded,’ they added.

It seems unlikely that this review mill is the only one in existence

Anna Pendlebury, publishing ethics specialist at the Royal Society of Chemistry says citation manipulation is a concern for the whole industry and, as appears to be the case identified with the review mill, in some cases, a number of individuals may be involved.

‘With the presence of paper mills already affecting scholarly publishing, it seems unlikely that this review mill is the only one in existence,’ she adds.

‘We are pleased to see that many publishers are working together, alongside associations such as Committee on Publication Ethics and [the academic publishers’ trade association] STM, to combat these significant threats to scholarly publishing.’

Oviedo García says she has already found three more review mills that she is in the process of analysing since her blog was published by Predatory Reports in January. She notes that journals’ editors-in-chief and handling editors have a duty to check the quality of reviews. ‘If someone reviews several times a month, and he or she is doing research as well as teaching, continuously – that should ring [an alarm] bell,’ she says.

Chemistry World attempted to contact three of the reviewers named in Oviedo García’s blog post, but did not receive a response in time for publication.

No comments yet