More and more charities are investing in companies, and looking for returns on that investment, as an alternative to traditional grants

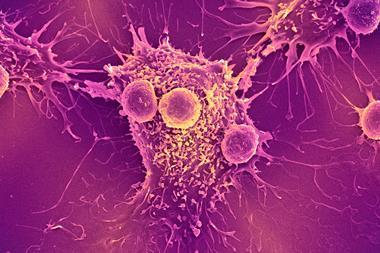

Charity is changing. Patient advocacy groups and medical research charities, frustrated by the lack of investment in the life-saving therapies their loved ones need to survive, are taking up the trade of venture capitalism – and it turns out, they’re pretty good at it.

Instead of traditional granting, where charities take donations and distribute them periodically, more organisations are adopting a model that falls under the umbrella category known as venture philanthropy. Investing their funds in companies, with the hope of returning both new drugs, and financial returns. For example, medical research charity LifeArc (formerly MRC Technology) recently sold a portion of its share of royalties from the blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda (pembrolizumab) which it helped bring to market, for $1.3 billion (£1 billion).

Venture philanthropists are guided by one simple principle: get useful treatments into the hands of patients, and make money doing it. In LifeArc’s case, those returns come from the stakes it holds in the companies it invests in, and sharing the royalties of successful treatments. These returns are then reinvested back into other potential treatments, creating sustainable cash flow for the charity and a financial incentive for companies and start-ups to research particular diseases. More often than not, the charities will act as partners as well as investors, offering ongoing consultation and guidance.

We’re different from the venture capital companies, because we have tremendous access to the experts in the field

This kind of thing isn’t new. In the late 1990s, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) in the US began investing in a company called Aurora Biosciences (now Vertex Pharmaceuticals). That partnership led to Kalydeco (ivacaftor), the first drug targeting the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis. The CFF sold its royalty rights to the drug for $3.3 billion in 2015. It’s no coincidence that it was CFF that led the charge here – as an ‘orphan’ disease, cystic fibrosis affects only a minute fraction of the population, so the financial incentives to develop treatments just weren’t there. Rather than sit on its hands and wait for the government to create incentives, the foundation decided to take action.

Other charities followed suit. The Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation now all have established venture philanthropy programs. Lee Greenberger, chief scientific officer of the Lymphoma and Leukaemia Society (LLS) says that its 11-year old therapy acceleration programme grew from its portfolio of academic grants. ‘Some of these academics had interesting therapeutic opportunities that could move into the clinic, but really didn’t have a funding mechanism or infrastructure to do that. So it was initially set up to accelerate opportunities into the clinic, primarily coming from academia.’

That has changed over time. Now, almost 80% of LLS funding goes into biotechnology firms – its portfolio consists of around 16 (mostly small) biotech companies, in which it invests around $2–10 million over a two to five year period, usually for Phase 1 or Phase 2 clinical trials. This is typical of the way charities invest – Phase 3 trials can cost upwards of $50 million, which most simply can’t afford.

More than money

One of charities’ primary assets, however, isn’t their capital, but their eye for identifying promising treatments in these early stages. The LLS receives over 600 grant applications every year – it knows what’s going on in research, and is paying close attention. ‘We’re sort of different from the venture capital companies, because we have tremendous access to the experts in the field, and we’re seeing what’s happening in the field almost as it’s developing in real time,’ says Greenberger.

The idea is to take that laser-like focus and to use it to invest in the risky stages of the R&D pipeline so that bigger, private venture capital firms or pharmaceutical companies can swoop in at a later stage to carry the work to the finish line. So far, the LLS has helped bring three US-approved therapies to market.

While much of the success of charities in the sector can be attributed to their expertise, another key factor stems from their unrivalled access to patient groups. Tanisha Carino is the executive director of the Faster Cures programme at the Milken Institute, an economic thinktank based in Santa Monica, US. The programme was set up 25 years ago to raise awareness about the different ways to improve funding and accelerate research. It now works with over a hundred patient advocacy groups.

‘There was a real awakening that the disease philanthropies that were led by patients played a critical role in catalysing the system to pay attention to what actually matters,’ says Carino. Patients suffering from the same rare disease, she explains, begin to collate information on the natural history of their disease, which in turn gives researchers a better idea of what problems to focus on. ‘When people say from bench to bedside, a lot of families say “No, it was from bedside to bedside”. And I think that’s where the power of venture philanthropy comes from…that that money is tied to a sense of urgency.’

Though venture philanthropy was originally the domain of rare diseases, the success of the model means that private venture funds are beginning to see the intrinsic value in partnering with charities in the market more broadly. At the beginning of July, Cancer Research UK (CRUK) partnered with Boston-based venture capital firm SV Health Investors, investing an initial £20 million into SV’s £200 million oncology investment fund. By partnering, CRUK also gets access to SV’s pool of management talent. This is important, since start-ups, which usually have a narrower focus and high discipline, tend to be a good way to bring research out of the academic lab and into the clinic. However, part of the trouble in getting start-ups off the ground is the difficulty in finding good management. This access to management talent, combined with CRUK’s scientific expertise, increases the odds of building a successful start-up – which means more potential treatments.

‘One of the fundamental tenets of venture philanthropy is making [your money] go further,’ says Tony Hickson, the chief business officer at CRUK. ‘We’ve seen a ten times leverage on our money by putting a cornerstone investment into this fund.’

Avoiding exploitation?

Not everyone is a cheerleader for this model. Sceptics call attention to the fact that many of the treatments brought to market by venture philanthropy come with hefty price tags – Kalydeco has a US list price of around $300,000 per year for a single patient – a cost which is met through insurance.

Paul Quinton is a researcher at the University of California San Diego, studying cystic fibrosis. He also suffers from the disease himself. Since the CFF’s sale of its rights to Kalydeco, he has been sceptical about venture philanthropy. ‘I think there’s a trade-off between altruism and venture philanthropy,’ says Quinton. Noting a desire for transparency, he worries about a potential conflict of interest in charitable foundations that profit from the drugs that their patients need.

He also says that he was disappointed with the high price of the drug, given the foundation’s involvement. ‘The price tag is something on the order of $300,000 a year now. It’s been that way since it came out five or six years ago. Well, it seems to me that the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation had a moral responsibility to go up against that and say: look, this is crazy.’

One of the fundamental tenets of venture philanthropy is making [your money] go further

Greenberger of the LLS says that his charity has very little input on price. ‘It’s clearly an important issue. With a lot of these new patented drugs and combinations, the cost is just getting prohibitive. Nevertheless, the number one goal is to get a solution for the patients such that diseases will either have long term control or cures. And we’re getting there.’

The debate on the high price of drugs that treat rare diseases has come up again recently owing to the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence refusal to pay for a combination drug which makes use of the active ingredient in Kalydeco. Orkambi (lumacaftor/ivacaftor), which costs £105,000 per year per patient, is approved in the EU for patients who hold a specific mutation; roughly half of the cystic fibrosis patient population. That’s about 5000 people in the UK. For drugs that treat such a small number of people, critics argue that venture philanthropy could be creating perverse financial incentives for pharmaceutical companies to research treatments that are overwhelmingly outside of the public interest.

‘If you had a pot of money and needed to allocate it, why do you allocate it to something that may not have as big of an impact to as big [a part] of the population? That’s one perspective,’ says Carino. ‘But if you’re a family member of a child with a rare disease, that perspective is irrelevant to you.’

‘The other thing I would caution is the premise that it’s a zero-sum game. That there’s a set pot of money that can only be allocated once,’ she adds. ‘That’s not true. We’ve seen growth of venture capital, I’m sure that we’ll see even more growth in the area of biotech, we’ve seen an increase in government funding and we’ve seen an increase in philanthropic funding.’

‘I don’t know whether I think venture philanthropy is a good thing or a bad thing, but I can tell you that I am convinced that for those organisations that get into it, there is an absolute need for transparency,’ says Quinton. ‘How they get that money and what they do with it has to be perfectly out in the open, so that everybody can see that there’s not some sort of underlying motivation or corruption that’s going to deteriorate the altruistic motives of philanthropic organisations.’

No comments yet