Academics across the US have the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) ‘China Initiative’ in their sights as cases prosecuted under this programme are being dismissed after wreaking havoc on the lives and careers of researchers in the country. They argue that the policy – created in 2018 under the Trump administration to pursue theft of intellectual property by China – creates a hostile environment for Chinese scientists and is tantamount to racial profiling.

The China Initiative has focused on researchers at US universities with undisclosed ties to China, for example through other universities, companies, or so-called state-sponsored talent recruitment programmes like the ‘Thousand Talents’ scheme. But opponents of the policy say researchers who are Chinese immigrants or of Chinese descent have been unfairly targeted. They point out that the DOJ has had to drop many of these cases, which upended the careers of numerous scientists, because they were flimsy, often based on charges of wire fraud and making false statements to government officials.

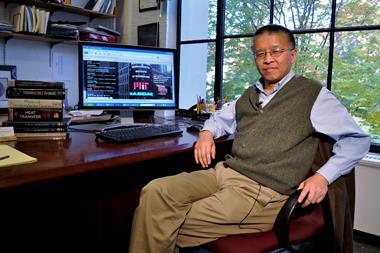

Most recently, University of Tennessee, Knoxville nanotechnologist Anming Hu, who was the first academic to go to a jury trial under that China Initiative, was acquitted in September after the espionage case against him crumbled. The Chinese-born Canadian citizen, indicted and arrested in February 2020, had worked for UT Knoxville since November 2013. The university fired Hu in October 2020 after suspending him without pay, and he was prosecuted by the DOJ twice. Now key faculty at UT Knoxville, including the senate faculty president, are calling on the university’s chancellor to give Hu his job back.

Hu’s case is similar to several that the DOJ dropped back in July, including one against Qing Wang, a former researcher with the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio for over two decades and professor at Case Western Reserve University. Born in China and a US citizen for about 16 years, Wang was arrested in May 2020 for allegedly hiding funding he received through a Chinese talent recruitment programme, and was immediately fired.

Another well-known case that has been tossed is that of Xiaoxing Xi, the former chair of Temple University’s physics department who was arrested in 2015 and charged with spying for China. At a virtual hearing of the House of Representatives’ science committee on 5 October, Xi recounted how armed agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) raided his home at dawn, held his wife and two young daughters at gunpoint, and took him away in handcuffs. Born in China and earning his PhD in physics there, he and his wife came to the US in 1989 and eventually became US citizens.

‘Our life had been wrecked’

The charges that he passed sensitive US technology to China were ‘totally false’, Xi testified. He said it took almost four months for the US government to drop the case against him. This only happened after leading experts in his field provided affidavits saying that the emails he had sent were not about the so-called ‘pocket heater’ technology that he was working on but were instead about his own widely published research. ‘But our life had been wrecked,’ Xi stated.

The exact same early morning raid scene was repeated later for Hu and Wang, he said. In 2017, Xi sued the FBI for violating his constitutional rights, alleging that he was targeted due to his ethnicity. That suit is reportedly still pending.

‘People are terrified, they are afraid that they may be the next,’ Xi told the congressional committee. The problem is that US law enforcement officials consider Chinese professors, scientists and students so-called ‘non-traditional collectors’, or spies, for China, he said. ‘We are presumed guilty until proven innocent,’ Xi continued. ‘It is only a matter of time and chance that any scientist of Chinese descent may get the knock at his or her door by FBI agents and be snatched away.’

Without serious evidence that they have stolen technology, academics are being charged for failure to disclose their activities in China, Xi testified. He noted that academic collaboration with China was once encouraged by the US government and universities, and joining a Chinese government talent programme was celebrated just like similar prestigious talent programmes in other countries.

‘This is not fair,’ he stated. ‘It has not always been clear what professors are required to disclose – when the policy towards academic collaboration with China has changed so abruptly, it is only fair to communicate the new policy clearly to everyone before throwing people in jail.’

‘This will cost the US’

Two particularly high-profile cases are those against nanotechnology pioneer Charles Lieber, who was arrested in January 2020 for allegedly failing to disclose millions of dollars in research funding from China, and Gang Chen, a Chinese American researcher who served as director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) nanoengineering laboratory and was arrested in January for his links to China. In both instances, colleagues and prominent scientists came to their defence and picked apart the legal case against them.

Several scientists in the US have already been jailed for failing to declare their links to Chinese research programmes. They include Meyya Meyyappan, an India-born US citizen and former senior nanotechnologist at Nasa, who was sentenced to 30 days in federal prison in mid-June and a rheumatology researcher at Ohio State University, Song Guo Zheng, who was sentenced to 37 months in prison in May, and was also ordered to pay more than $3.4 million (£2.5 million) in restitution to the US National Institutes of Health for research fraud.

In his testimony, Xi cited data from a September 2021 survey by the American Physical Society, as yet unpublished, which shows that nearly one in five physicists in the US have either chosen – or been directed – to withdraw from professional activities with colleagues based outside the US because of research security guidelines.

These preliminary data further reveal that more than 43% of the international physics graduates and early career scientists perceive the US to be an unwelcoming country for international students and scholars, he said. The survey also indicates that at least 40% of international, early career scientists studying or working in the US believe that the response to research security concerns makes their decision to stay in the US long term less likely or much less likely.

‘This is huge,’ Xi warned. ‘This will cost the US to lose its leadership in science and technology faster than anything the Chinese government can do.’

Academics is the US are similarly concerned. Nearly 200 Stanford University faculty, including Nobel prize winners Paul Berg and Steven Chu, signed a letter to the attorney general Merrick Garland in September requesting that he terminate the China Initiative because it ‘disproportionally targets researchers of Chinese origin’ and is harming US science and technology.

Harsher penalties

More than 200 professors at the University of California, Berkeley have also endorsed the same letter, and Xi said a similar letter is being circulated among his colleagues, but some are afraid to sign on. ‘Some have told me that they fully support the letter, but out of concern about the possible consequences, they will not sign it,’ he stated.

Emerging data supports this hesitancy. A recent white paper by a non-partisan organisation of prominent Chinese Americans in business, government, academia and the arts, examined information on nearly 300 defendants charged under the US Economic Espionage Act (EEA) between 1996 and 2020, and found that those with Asian or Chinese last names were punished twice as severely as those with more western names. In addition, the analyses showed that the prison sentences of Chinese and Asian defendants was double that of western defendants.

The white paper also revealed that the actual charges against university staff rarely include accusations of espionage. In addition, only 3% of the alleged thefts of trade secrets under the EEA occurred in research institutions. The study also found that 27% of presumed Asian American citizens charged under the EEA were not convicted of any crimes. In total, the analysis showed that one in three Asian Americans alleged to have committed espionage may have been falsely accused.

Maria Zuber, MIT’s vice president for research and co-chair of the US National Academies’ science, technology and security roundtable, agrees with Xi that university and government funding agency reporting requirements must be clarified when it comes to research collaborations with China and other countries. At the 5 October congressional hearing, Zuber described significant confusion among MIT faculty about what actually needs to be disclosed with respect to such international arrangements and how it needs to be disclosed. As research agencies’ requirements have varied, she said there have been ‘inadvertent errors in disclosure’.

The issue goes beyond the US too. The Chinese government has established a network of more than 600 international outposts across the world to recruit foreign experts and scientists in order to acquire advanced technology and protected IP, according to analysis last year by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. The bulk of these recruitment stations are located in the US, with nearly 60 each in Germany and Australia, and more than 40 each in the UK, Canada, Japan and France.

Rising number of allegations

Meanwhile, the inspector general of the National Science Foundation (NSF), Allison Lerner, testified that her agency doesn’t have adequate resources to handle the growing number of allegations that China and other nations are stealing scientific know-how from the US. She said investigations pertaining to foreign influence programmes have grown dramatically over the last few years to the point where they now represent 63% of her office’s caseload. Lerner confirmed that her investigative office, which has about 20 employees, has seen an increase of about 1000% in cases referred by the FBI in recent years.

‘At this point, I think even if we doubled the number of people in our investigative office, we would still be hard-pressed to keep up with the number of allegations that are coming in,’ she said. ‘These cases tend to be complex and time-consuming, and in responding to them we have sorely tried our staff who are doing their level best but working beyond their capacity.’

Although membership of a foreign government talent recruitment programme is not illegal, Lerner said it is important for the NSF to know about a researcher’s involvement because some of them elicit unethical or even potentially criminal behaviour. Members of these schemes are often required to enter into contractual relationships with a foreign government, which strongly favour its interests over the researcher’s.

‘In exchange for funding, and maybe even a lab for the researcher, the foreign government exerts control over the researcher’s intellectual property, the types of research she conducts and, in some cases, where she conducts it, and who works in her lab,’ Lerner explained. The NSF and other government science agencies must be aware of the researcher’s membership of such a programme in order to address possible conflicts of interest or commitment, questions about control over the researcher’s intellectual property, or other concerns, she added.

2 readers' comments