Basic chemical plant closures highlight strain on European industry

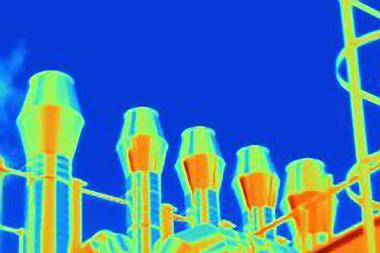

The last few weeks have been a tough time for basic chemicals manufacturing in the UK and Europe. Sabic has reversed its decision to refit and re-open its olefins cracker in Teesside, UK; Prax group, operator of the UK’s Lindsey oil refinery on the banks of the Humber river, has entered administration; and Dow Chemical has confirmed that it will close three European chemicals sites by the end of 2027 – an ethylene cracker in Böhlen, Germany, a chlor-alkali and vinyls plant in Schkopau, Germany, and a basic siloxanes plant in Barry, UK.

While each of these industries faces its own challenges, they are united by the themes outlined in Anthony King’s exploration of the pressure facing Europe’s steam crackers: higher energy and feedstock costs than international competitors, coupled with older plants that are less efficient than bigger, newer ones being built elsewhere. Slower-than-expected growth in demand has also led to oversupply that keeps prices low and makes it harder to recoup increased costs.

If costs go up but prices can’t follow, profit margins can quickly swing to losses. But simply pausing production is not an option – shutting down such continuous plants is a major undertaking. Plants can run below capacity, aiming to ride out the cycle, but may end up burning through large amounts of cash. If that loss can’t be offset by a more profitable segment of a company’s operations (as it may be in integrated or diversified chemicals firms), then the future of the whole operation is challenged. Once shut down, these facilities rarely re-open.

But basic chemicals are the foundation of huge swathes of manufacturing industry, and their closures will have significant long- and short-term impacts on regional production networks. As global trade is disrupted by political trade wars, relying on imports becomes a vulnerability. Efforts in China to boost domestic production (including significant state support) as well as the Middle East’s push to make more higher-value petrochemicals – rather than exporting crude oil – have exacerbated pressure on Europe’s aging plants.

Europe’s industry has the opportunity to lead a transformation to more sustainable feedstock and energy usage. Plants that want to survive declining fossil carbon use will need to adapt and decarbonise – for example by developing alternative heat sources as the UK’s Stanlow refinery is exploring, or switching to bio-based inputs as Versalis plans at one of its crackers in Italy. But investing in these (expensive) transitions while global competitors continue exploiting their existing advantages is an uphill struggle and a hard sell to shareholders.

The UK government has stepped in to temporarily maintain operation at the insolvent Lindsey refinery while a potential sale is negotiated, ensuring continuity of fuel supplies. In the longer term, the pace of decline or transformation across the basic chemicals landscape will be heavily influenced by the strategic importance various governments place on domestic production (and therefore what level of support they offer), and the extent of global agreement on prioritising carbon emissions reduction over fossil-fuelled growth.

No comments yet