The rise of ChemRxiv might mean that chemists can tackle thornier cultural problems

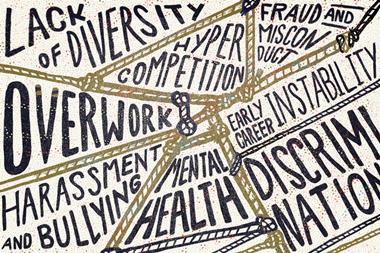

A lot of the articles in this issue address the thorny problems in academic research culture. The interlocking tangle of an ultracompetitive environment, the inappropriate use of metrics, the pressure to produce eye-catching results and get them published, an already less-than-diverse workforce and so on all add up to a problem that can’t be fixed by an individual, or even individual institutions.

But just because a problem seems intractable is no excuse for not tackling it. As Paul Walton, a chemist at the University of York, says in Rachel Brazil’s feature on p22, one positive change of the past couple of decades has come in health and safety. That’s something that needed a cultural shift, and it’s happened – some of the practices of our predecessors (often recounted on our letters page) elicit shudders from modern lab workers.

On p52, Nina Notman explores another small corner of behaviour that’s slowly changing for the better. Since 2017, the ChemRxiv depository has allowed researchers to upload their unpublished research papers before submitting them to traditional journals. These preprints, as they’re called, are then available for anybody in the world to download and read, free of charge.

But just because a problem seems intractable is no excuse for not tackling it. As Paul Walton, a chemist at the University of York, says in Rachel Brazil’s feature about research culture, one positive change of the past couple of decades has come in health and safety. That’s something that needed a cultural shift, and it’s happened – some of the practices of our predecessors (often recounted on our letters page) elicit shudders from modern lab workers.

In her feature on ChemRXiv, Nina Notman explores another small corner of behaviour that’s slowly changing for the better. Since 2017, the ChemRxiv repository has allowed researchers to upload their unpublished research papers before submitting them to traditional journals. These preprints, as they’re called, are then available for anybody in the world to download and read, free of charge.

Preprint servers are not new – arXiv, originally for physics, has been around for 30 years – but a chemistry-focused one, with the backing of the American Chemical Society (and now its counterparts in the UK, Germany, China and Japan), was.

Chemists have generally been quite conservative in how and where they publish, with a variety of reasons usually suggested. Smaller research group sizes (when compared with multinational physics collaborations such as Cern) is one, and another one is many chemists’ proximity to commercial endeavours. It’s not quite the secret codes of the days of alchemy, but perhaps some of the same feelings persist.

Now chemists are using ChemRxiv with a variety of motivations. Some want to get feedback from their peers in a broader way than traditional peer review achieves. Others want to get their ideas and achievements date-stamped without being at the mercy of journal editors and reviewers.

Whatever the reasons behind its increasing acceptance, it’s good to see more papers appearing on ChemRxiv for the world to read – and even better to see that people’s attitudes can change. If that’s the case, there’s hope for the big intractable problems too.

No comments yet