‘Clock transitions’ could make it possible to discover if a flaw in the Standard Model exists – without the need for high-energy particle colliders

High-energy physics is in a peculiar position. Having tested the Standard Model – the description of all known particles and forces, bar gravity – to what might have been expected to be its breaking point, we’ve found no clear flaws in that theoretical edifice. And yet it accounts for what makes up just 5% of the known universe, while dark matter and dark energy remain mysterious. Nor do we know why this much ordinary matter exists at all, given that cosmological theories predict that the Big Bang should have formed equal amounts of matter and antimatter that should mutually annihilate.

With such puzzles in mind, particle physicists have drawn up plans for an even larger successor to the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at Cern, which completed the Standard Model by identifying the Higgs boson in 2012. The Future Circular Collider, overlapping the LHC’s circular tunnel like a Venn diagram, would have a whopping circumference of 100km and give access to larger energy scales, at an estimated cost of $9 billion (£7.3 billion).

But there’s a cheaper way of looking for physics beyond the Standard Model that we can do already in the laboratory – using molecules. Spectroscopic and interferometric measurements on atoms and molecules cooled to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero have become so accurate that tiny deviations from theory, indicative of ‘new physics’, can be reliably sought.1 Such studies have been going on for decades in parallel with atom-smashing. In 1997, for example, a team based at Jila in Boulder, Colorado, US, reported the signature of parity violation – basically a breakdown of left–right symmetry, first seen in 1956 by Chien-Shiung Wu and her collaborators – in electronic transitions of caesium atoms.2

One potential crack in the Standard Model is a breakdown of time symmetry – the principle that the fundamental laws of physics look the same whether running forwards or backwards in time. (Time symmetry violation is essentially equivalent to simultaneous violation of the conservation of charge and parity, CP.) This violation seems to be one way to generate the asymmetry between the amounts of matter and antimatter in the universe in cosmological models, and is associated with new, very massive particles. But experiments on ultracold molecules could disclose another predicted consequence of time-reversal violation: an electric dipole moment of the electron (eEDM). That’s to say, the violation predicts that the electron will have an asymmetric distribution of charge along its spin axis. If so, we should expect tiny shifts in some of the electronic transitions of atoms and molecules.

Such shifts would be more apparent in some molecules than others. Specifically, those made from very heavy atoms and with their own dipole moment contain very high internal electric fields, the strength of which determines the spectral shifts. In 2018 an international project called the ACME Collaboration reported improved limits on the electron’s EDM from measurements on thorium oxide3 – itself an improvement of the first ACME experiment in 2014.4 The measurements themselves used laser fluorescence to probe the frequency at which an electron in the molecule precesses (rotates) in an applied magnetic field. The ACME team’s limits on the possible scale of the eEDM implied that any new particles associated with time-reversal asymmetry would have to have masses greater than at least 3TeV – within the reach of the LHC, although the more likely mass limit of 30TeV is not.

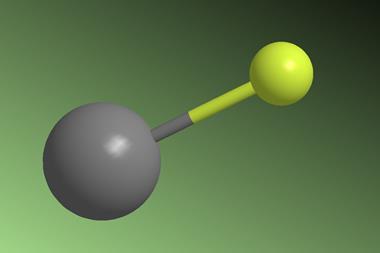

One of the challenges for such studies of the eEDM is that the measurements are extremely sensitive to stray magnetic and electric fields in the lab. One solution is to tune the polarisation of the molecules with an applied electric field such that they acquire near-zero sensitivity to magnetic fields while remaining in a state where the eEDM can be measured accurately from electron precession. In January a team with members based at Caltech and Harvard described how to do that using CaOH as the test molecule (although actual eEDM determinations would use heavier equivalents, like YbOH or RaOH).5

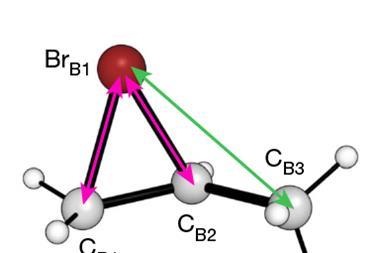

Now the Caltech group, led by Nicholas Hutzler, has reported another way to insulate such molecules from both random magnetic and electronic fields: by probing CP violation using so-called ‘clock’ transitions, for which such field-induced shifts ‘magically’ cancel out.6 They show that a wide range of diatomic and polyatomic molecules have transitions like this, using as an example a bending vibration in the electronic ground state of 173YbOH. The notion of these clock transitions was proposed three years ago to deal with the problem of magnetic-field sensitivity7 and involves hyperfine states, caused by interactions between the electrons and the nuclear spin. But eliminating sensitivity to electric fields too, while still maintaining good sensitivity to CP violation, should bring us even closer to finding new physics in molecules – if indeed it exists.

References

1. M S Safronova et al, Rev. Mod. Phys., 2018, 90, 025008 (DOI: 10.1103/RevModPhys.90.025008)

2. C S Wood et al, Science, 1997, 275, 1759 (DOI: 10.1126/science.275.5307.17)

3. ACME Collaboration, Nature, 2018, 562, 355 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0599-8)

4. J Baron et al, Science, 2014, 343, 269 (DOI: 10.1126/science.1248213)

5. L Anderegg et al, arXiv, 2023, DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2301.08656

6 Y Takahashi et al, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2023, 131, 183003 (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.183003)

7. M Verma, A M Jayich and A C Vutha, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2020, 125, 153201 (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.153201)

No comments yet