Ben Valsler

Food fraud, the adulteration or counterfeiting of food products, is a serious problem – and while paying over the odds for Manuka honey that turns out to be little more than syrup may hurt your wallet, some types of food fraud are much more insidious. Here’s Katrina Krämer.

Katrina Krämer

In May 1981, people in central Spain started falling ill. At first, it appeared to be a case of widespread pneumonia: symptoms included fever and breathing difficulties, vomiting, nausea and muscle pain. But the disease proved resistant to antibiotics and soon patients developed pulmonary hypertension, embolisms and heart infections. Within a month, the mysterious illness spread across northwestern Spain, affecting some 25,000 people.

Symptoms were long-lasting and persistent, and over the course of the next two years the disease claimed the lives of around 300 people. Survivors often ended up with chronic conditions such as liver and autoimmune diseases, and even neurological disorders. Although it is hard to know for sure, the long-term death toll is estimated to be about 1000.

Spanish health officials struggled to find the cause of the obscure disease. Among the initial suspects were poisoned onions, strawberries and asparagus. Many innocent pets were killed as some reports suggested that animals carried and transferred a virus.

But all signs eventually pointed towards an entirely different culprit: adulterated cooking oil. The disease, which became known as toxic oil syndrome, had been caused by aniline-laced oil.

Aniline is a simple compound, a benzene ring attached to an amine group. But as an important base material for polyurethane foams, several million tonnes are produced every year.

Despite its pungent odour of rotten fish, aniline has long been a key compound for industry. The Baden Aniline and Soda Factory is even named after it, although it is now better known under its acronym BASF. Now one of the world’s largest chemical suppliers, BASF started out as a producer of aniline dyes.

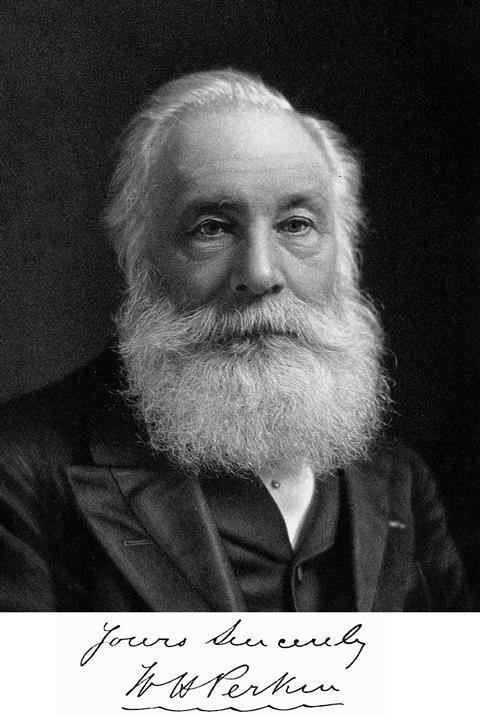

William Henry Perkin’s discovery of the synthetic purple pigment mauveine in 1856 revolutionised the dye industry, but it also drove up the demand for aniline – back then an expensive chemical. Luckily, in 1861, French chemist Antoine Béchamp discovered that he could make aniline from nitrobenzene by reducing it with an iron catalyst. The method was simple enough to be scaled up to multi-tonne scale, hailing the era of cheap aniline. With it came many more azo dyes such as aniline yellow, the magenta-coloured fuchsin and the blue induline.

So how did aniline end up in Spanish cooking oil? Curiously, food safety laws might have had something to do with it.

In the 1960s, rapeseed oil was becoming increasingly popular for cooking. Producers marketed it as being especially suitable for food while being much cheaper than olive oil. In the early 1970s, Sweden’s medical research council was the first to question whether the oil was really safe for human consumption. It turned out that natural rapeseed oil contains around 50% erucic acid – a compound that caused heart disease in rats and mice.

While plant geneticists scrambled to develop a low-erucic acid rapeseed variety – now known as canola – many countries followed Sweden in banning the oil altogether. In Spain, importing the oil for human consumption was illegal, but it was still sold as a machine lubricant. To avoid it being used as cooking oil, 2% of aniline was added.

But you can’t make much from selling machine lubricant. Olive oil, on the other hand, is a key component of Spanish cuisine and people have always paid good money for it. What most likely happened is that some shady oil importers and vendors decided to sell machine oil on local food markets – in unmarked containers so nobody would expect a thing. They distilled the oil in an attempt to get rid of the aniline and its unpleasant taste. This, however, only converted the chemical into a mix of derivatives, including anilides and phenylaminopropanols – the compounds that were likely responsible for the disease. I say ‘likely’, because to date, scientists have not managed to firmly link a single compound to victims’ symptoms.

In early July 1981, the Spanish government destroyed all suspect oil, launched strict food safety checks on local markets and offered to exchange cooking oil for pure olive oil at their expense. After that, the number of new cases decreased abruptly. But out of the 40 merchants accused of making and selling poisoned oil, 24 were acquitted.

Despite decades spent investigating the disease, animal studies have failed to reproduce the effects of tainted olive oil seen in 1980s Spain. Alternative theories place the blame on tomatoes contaminated with organophosphate fertilisers, although patients’ symptoms were different to those associated with phosphate poisoning. Some believe that it was due to a biological weapons accident at a US airbase near Madrid. Nevertheless, a 200-page World Health Organisation report released in 2004 argues that epidemiological evidence leaves little doubt over what caused the disease: aniline poisoned oil.

Ben Valsler

That was Katrina Krämer with aniline and the case of the poisoned oil. Next week, Mike Freemantle returns with an easy-to-digest energy boost.

Mike Freemantle

One recipe, for arrowroot jelly, required boiling up water, sherry or brandy, nutmeg and sugar and then adding a mixture of arrowroot and cold water before boiling again. ‘It is very nourishing, especially for weak bowels,’ wrote English cookbook author Maria Rundell.

Ben Valsler

Get the nourishment you need with Mike next time. Until then, drop us a line with your ideas for compounds to cover on the Chemistry in its element podcast. Email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet