Meera Senthlingam

This week, discover the darker side of a deceivingly toxic flower. Revealing all is Emma Stoye…

Emma Stoye

In rainy Britain, garden flowers are often a much better indicator of the time of year than the weather. Snowdrops are a welcome sign that winter is coming to an end, daffodils and bluebells signal the start of spring, and if there’s one plant that shouts ‘summer is here!’ it’s the foxglove.

The great sixteenth century herbalist John Gerard got a lot of things right, but when he said foxgloves were ‘of no use’, he could not have been more wrong. Its delicate pink flowers look innocent enough, but some of the plant’s older names – ‘witches’ gloves’ or ‘dead man’s bells’ – betray its darker side.

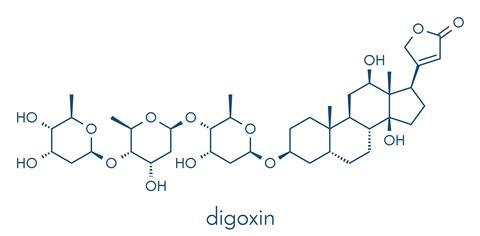

The flowers, leaves, roots and seeds of the foxglove are all highly poisonous. They are full of compounds called glycosides – which contain a steroid bonded to a sugar – including the deadly cardiac glycoside digoxin, which wreaks havoc on the heart. Although its exact mode of action is poorly understood, digoxin is thought to disable the sodium–potassium ion pumps in heart cell membranes, causing a rise in the concentration of sodium and calcium ions inside these cells. This interferes with the transmission of electrical signals through the heart, which slows, and eventually stops, the heartbeat.

You might assume that this would lead to a peaceful death – but you’d be wrong. In most cases, death is brought about by a massive heart attack, which is preceded by an accelerated heartbeat. This may seem odd, and has led to the common misconception that digoxin speeds up the heart. In fact, this spike in cardiac activity is a short-lived response to distress signals from the oxygen-starved brain. On top of that, foxglove leaves themselves are a powerful emetic, so the lethal effects of digoxin are often accompanied by vomiting, and various other side effects including stomach pains, blurred vision, headaches and hallucinations. Overall, it’s not a nice way to go.

There have been many incidences of accidental digoxin poisoning – usually when people suck the foxglove flowers trying to drink the nectar. The plant was certainly a known poison during the middle ages, and was used in trials by ordeal – with those accused of crimes being forced to swallow some of the poisonous leaves and deemed innocent only if they survived. Digoxin has even been used as a murder weapon much more recently. In 2008, 42-year-old Lisa Allen from Colorado in the US attempted to poison her husband with foxglove leaves hidden in a salad. He survived the ordeal, but was admitted to hospital with heart palpitations and stomach cramps.

But on the flip side, digoxin can actually be therapeutic in small doses. Its ability to slow down the heart is a useful tool for treating fibrillation, a condition where different muscles in the heart contract irregularly, and out of synch with one another.

Again, its medicinal use goes back centuries. Foxgloves have long been used in folk medicine, and in the eighteenth century they caught the eye of an English doctor called William Withering. He had heard rumours that ‘wise women’ in his native Shropshire had been successfully treating a condition called dropsy with an infusion made from leaves of the foxglove. Back then, dropsy was the name given to any kind of soft tissue swelling, but we now know that dropsy-like fluid on the lungs is often a side-effect of heart problems.

Withering decided to investigate this, and experimented on patients attending his clinic using a rather ethically suspect trial and error approach, giving different doses of the plant to patients suffering from various illnesses. He found that the wise women appeared to be right – foxglove leaves did indeed reduce symptoms of dropsy, and could also be used to treat heart failure, although in high doses it would stop the heartbeat altogether.

Withering’s work is regarded by many as the beginning of modern pharmacology. He meticulously recorded all of his observations – including the failures – and published them in 1785 in An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses: with practical remarks on dropsy, and other diseases. This was the first English text to describe the therapeutic effects of a drug.

Over the next two centuries, other scientists followed Withering’s lead, and digoxin was eventually extracted and identified as the active ingredient in foxglove. It became firmly established as a treatment for heart conditions during the second half of the 20th century, and remains one of the go-to drugs for atrial fibrillation.

Digoxin is quite unusual among plant-derived pharmaceuticals, as the foxglove plant is still the primary source. Most drugs that started out as herbal remedies are now synthesised in the lab, which saves on the hassle of cultivating the plant. But synthesising digoxin is both difficult and expensive, so it is extracted from the dried leaves of Digitalis lanata foxgloves grown commercially in parts of Europe.

So next time you see a foxglove, remember they’re a factory for digoxin – which can be lethal or lifesaving. As the great alchemist Paracelsus once said: ‘There are no poisons, only poisonous doses.’

Meera Senthlingam

Chemistry World’s Emma Stoye there with the beneficial, yet potentially fatal chemistry of digoxin.

Next week, we move from toxic flowers to mind altering leaves…

Simon Cotton

In his humorous novel Black mischief, the 20th century English writer Evelyn Waugh wrote ’Mahmud el Khali bin Sai’ud sat among his kinsmen, moodily browsing over his lapful of khat’.

He was actually referring to some green leaves. Khat, or cott, is the name given to the leaves of an evergreen shrub (Catha edulis) that grows in East Africa; some call it ’the flower of paradise’.

Meera Senthlingam

And discover the chemistry behind this paradise by joining Simon Cotton in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until next week, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet