Ben Valsler

This week, Georgia Mills introduces the simple compound that with a deceptively complex role in motivation and addiction.

Georgia Mills

Do you ever find yourself checking your social media for the tenth time in an hour, or being unable to stay away from games like candy crush? The crafty little chemical responsible is dopamine.

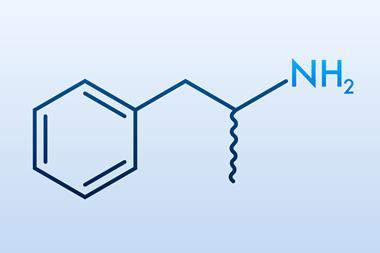

Composed of just carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen, dopamine looks, in its chemical structure, a little like a tadpole with horns. And this molecular tadpole causes massive changes in the brain and body.

It acts as both a hormone and a neurotransmitter, and regulates several important functions – from attention and emotion to learning and motivation. Dopamine also plays a part in sexual gratification and in nausea, hopefully never mixing the two.

We synthesise dopamine directly from the amino acid tyrosine, which is found in almost all the protein we eat. An enzyme called tyrozine hydroxlyase attaches an additional hydroxyl group to create dopa and give the structure its ‘horns’, then dopa decarboxylase removes the carboxyl group from the ‘tail’ to create dopamine. This process takes place inside neurons in the brain, or in adrenal glands in the body, but never the twain shall meet – dopamine cannot cross the barrier between our brain and the rest of the body.

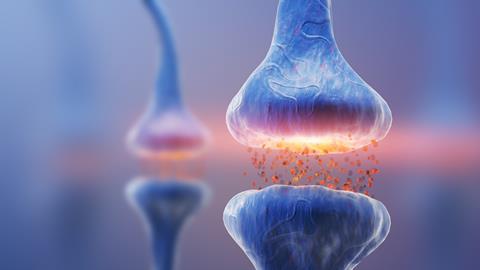

Dopamine works its magic by binding to specific receptors on the surface of cells. This controls the rate of certain cell processes, depending on cell and receptor type.

Problems in creating or absorbing dopamine are associated with several disorders. Low levels of dopamine are associated with Parkinson’s disease, an illness where sufferers have tremors and difficulty with movement.

Dopamine is also implicated in schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, depression and hyperactivity disorders, although determining its exact role is proving difficult.

However, dopamine is probably most famously associated with addiction.

Scientists have discovered that dopamine contributes to the little happy feeling you get when engaging in a rewarding behavior.

Addictive drugs, such as cocaine and methamphetamines can cause a surge of dopamine, or prevent it being reabsorbed, which can lead to feelings of aggression, euphoria or intense arousal. A particularly powerful surge of dopamine in the brain’s pleasure centre, the nucleus accumbens, is thought to be one of the reasons addictive drugs are so hard to shake.

But dopamine is not just a pleasure chemical - it’s key in learning about rewards. Throughout our evolution this has been very very useful. If we find a certain pattern of behavior results in a reward – ie rooting through bushes for berries results a tasty, sugar-rich treat – having this pattern reinforced is a good idea. Even if there aren’t any berries, the expectant cells waiting for the dopamine send out a specific signal. And when we find a treasure trove of berries, yippee! The pleasant surprise is compounded by even more dopamine.

Food makes for a simple example, but social media and casual games work seem to work in a similar way, repeating the same behaviour with frequent but unpredictable rewards – which keeps us coming back.

Addictive drugs can overload dopamine circuits, so people may need ever larger doses to get the same effect and can find other rewarding things in life give them less of a buzz. This is reflected in people who have naturally low occurring levels of dopamine, who often exhibit addictive personalities and thrill seeking behavior, needing to throw themselves out of a plane to feel that sweet reward sensation.

Many addictive substances and behaviours are linked to dopamine, but it’s important to emphasise that not everything that causes a dopamine reward is addictive, and articles likening the addictiveness of cheese to cocaine fall into this trap.

Dopamine is much more than a simple ‘pleasure chemical’ causing addiction wherever it goes, but even though it was first synthesised in the lab over 100 years ago, scientists are still slowly getting to the bottom of its many roles – provided they can stay off social media long enough to get any work done.

Ben Valsler

That was Georgia Mills with a little hit of dopamine. Next week, Patrick Hughes with an enduring cancer conspiracy.

Patrick Hughes

First isolated in 1830 from bitter almond seeds by Pierre Jean Robiquet, amygdalin was used as an anti-cancer treatment in the mid-19th century in Russia, and again during the 1920’s in the United States, but use came to a halt after treatment was found to be too toxic.

Ben Valsler

Join Pat to find out why a drug deemed too toxic to treat tumors is still talked of online as a potential cancer cure almost one hundred years on. Until then, get in touch in the usual ways – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet