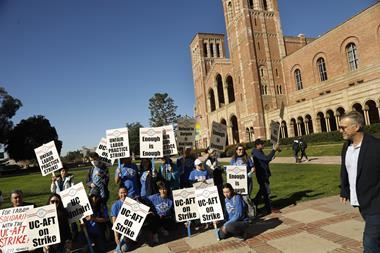

More than two weeks after nearly 50,000 academics went on strike at the University of California (UC) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory over pay and conditions, UC has reached a tentative agreement with academic researchers and postdocs. The strike continues, however, as union sections representing academic student employees and student researchers negotiate with the university.

The academic researchers and postdocs that reached agreement with UC represent about 12,000 of the workers who have been on strike. The remaining 36,000 academic student employees and student researchers are still trying to strike a deal with the university, according to Neil Sweeney, the president of the union of postdocs and academic researchers. UC student researchers last made a compensation proposal to the university 13 days ago and UC has not yet responded, according to the union.

‘The historic tentative agreements that were reached [on 28 November] really increase the quality of life for postdocs and academic researchers, not only with increasing compensation, but the ability to have more time off with our families when necessary, as well as to cover childcare expenses, and being able to have better protections and work environments, including more stability and job security,’ said Jade Moore, a postdoc in radiation oncology at UC San Francisco and a member of the postdoc bargaining team.

‘The lowest paid postdocs right now who make $54,500 (£44,860), by next October – in one year – will get a $12,000 salary increase to over $66,000,’ Sweeney explained. That’s an increase of 20–23%, which will be followed by annual pay rises of at least 3.5%. That will mean all UC postdocs will be paid more than $70,000 by the end of the five-year contract, he added. ‘It’s the largest salary increase I’ve seen for postdocs in the country.’ He noted that, by the end of the contract period, the median salary of UC postdocs would be higher than those at Stanford.

For academic researchers, UC has agreed to annual salary increases of 4.5% in the first year, 3.5% in the second, third and fourth years, and 4% in the 5th year. Overall, a typical researcher will receive a rise of 29% over the lifetime of the contract.

These tentative contracts that UC agreed to for its postdocs and academic researchers also include what Sweeney called ‘industry-setting protections’ against abusive conduct and bullying, which he described as a pervasive problem in academia. There are also new protections added for disabled workers, as well as improvements in paid parental and family leave – all postdocs would receive full pay for eight weeks, starting in 2023.

A ‘new paradigm’ for academic workers

This is the largest academic strike in US history, and Sweeney suggested that it marks an important shift. ‘These two contracts, and the contracts that will come hopefully in a short number of days for the other two units, will really set the standard for a new paradigm for academic workers in the US,’ he stated.

Lexie McIsaac, a postdoc in computational chemistry at UC Berkeley and an organiser in the union, is very pleased with the postdoc contract that’s been negotiated. She says the members of the postdoc bargaining unit will ratify it by 9 December, but stresses that postdocs and academic researchers remain on strike in sympathy with striking academic student employees and student researchers.

‘For me personally, the main thing is just having a little more financial wiggle room – this is a very high cost of living area, so having a raise that keeps up with inflation is really important for being able to live and work here,’ McIsaac tells Chemistry World. ‘One of our biggest wins that I’m most excited about is that we doubled our amount of paid parental leave,’ she adds.

McIsaac notes that the energy out on the UC picket lines is very high. ‘Postdocs are really excited to see the graduate students get the same type of wins that we’ve seen,’ she says.

Since the strike began on 14 November, McIsaac hasn’t been at work. ‘For my lab, the majority of people are participating in the strike, and our adviser has cancelled all meetings – I think very little work is getting done.’ At other UC labs, she says, all the researchers have walked out together in solidarity and research has halted.

About 4000 people were out there striking in the first week, which is about half of all academic workers, McIsaac estimates. ‘It’s probably fair to say that the majority of the research has stopped if the majority of workers are out here,’ she says.

McIsaac herself is almost at the end of a research project and was hoping to publish a paper, but has put that on hold to join the picket line. ‘I think it’s just super important to fight for equitable working conditions, so I was happy to make that sacrifice,’ she says.

As the UC system is such a research powerhouse, accounting for 8.6% of total research expenditures at all US universities in 2018–19 and home to 10% of postdocs in the country, McIsaac foresees that the final contracts that result from the strike will set the standard for US universities. ‘In terms of abroad,’ she adds, ‘if we have better working conditions here, that will probably lead people to consider whether they want to go to a university in the UK versus something that pays higher, elsewhere … globally, all these universities are competing for a lot of the same people.’

No comments yet