We’ve marked two important anniversaries in Chemistry World recently: 200 years since Michael Faraday first isolated benzene and 100 years since Cecilia Payne made her discovery that our sun is a ball of incandescent hydrogen and helium. These two moments have had a profound impact on science and society, and they are still very much relevant today.

What began with benzene

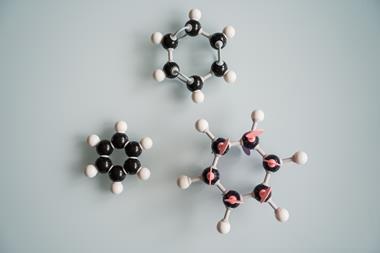

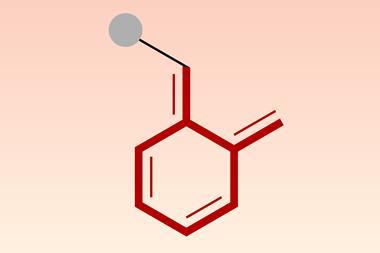

Benzene has become an icon of chemistry. The ring itself is an elegant example of chemistry’s talent for reducing layers of complexity into a simple symbol that crams conceptual richness in every aspect of its form. A mere hexagon to the uninitiated, to chemists it represents generations of development in the theory of structure and bonding, and in organic chemistry research and industry.

The modern chemical industry can trace its roots back to benzene, largely thanks to Charles Mansfield isolating the archetypal aromatic compound from coal tar in 1845. Benzene’s derivatives – aniline in particular – were pivotal in its history and William Perkin’s invention of mauveine in 1856, the first of the coal tar dyes, was effectively the genesis of an organic chemicals industry.

As Philip Ball notes, previous celebrations of benzene’s birthdays have leaned heavily on these industrial links. By 1925, when Payne’s PhD thesis was giving hydrogen its moment in the sun, industrial benzene production was already well established and the growing industry of synthetic dyes it supported became a founding component of the UK’s chemicals giant ICI just a year later in 1926.

Yet today, the chemicals industry is facing an almost existential crisis in the UK and Europe amid tough trading conditions and ballooning energy costs. Our feature on sustainable refineries picks up an aspect of that story, looking at how the UK’s remaining oil refineries are meeting the challenges of the 21st century.

Although refineries have kept the chemical industry supplied with feedstocks, their profitability has always depended on producing hydrocarbon fuels, and with the drive to decarbonise, falling demand for fossil fuels, high energy prices and competition from cheaper international rivals, the UK’s refineries have dwindled to just a handful. That decline was marked with another centenary last year when, 100 years after the site was established, Ineos announced that it would close its Grangemouth refinery in 2025.

As the experts in our feature note, however, the transition to cleaner, more sustainable practices also brings new opportunities for industry. The Phillips 66 refinery in the Humber, for example, has been able to capitalise on its graphite production to supply anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Producing hydrogen to meet the energy demands of a net-zero economy is another promising possibility, as well as producing sustainable fuels and feedstocks.

A future of fusion?

And as the world moves towards that clean energy future, it’s Payne’s contributions that might yet lead to one of the biggest prizes.

When Payne revealed the truth of hydrogen’s place in the universe a century ago, her discovery was treated with scepticism. But it ultimately helped to prove that stars are elemental furnaces – fusing lighter elements into heavier ones – and our understanding of that fusion process then developed through the 20th century. Today, there is the tantalising prospect that this process could be harnessed to generate energy on Earth.

Fusion is on the minds of many countries, and the UK is no exception with its industrial strategy, published on 23 June, promising an ambitious investment of £2.5 billion. It’s also promising to see that strategy recognise the essential importance of the country’s existing industries, including chemicals, and the need to support them with lower energy costs and decarbonisation initiatives. Strengthening these foundations of the economy ensures that the next generation of scientific discoveries can keep changing the world for the better, for centuries to come.

No comments yet