The battle for three scientists to find their voice

Moments before I stand in front of a crowd and speak, I feel a familiar, imaginary hand clenching around my neck and turning my tongue into wood. I have had a stutter for as long as I can remember. It causes stage fright, has led to bullying and given rise to insecurities. Gradually, I accepted my speech disorder and eventually built my personality around it. But even now I often try to avoid my trigger words or introduce pauses before I have to say them out loud.

Speech disorders are not considered a disability. The prevalence of errors in speech production ranges from 14% to 25% in small children, although drops significantly as they start elementary school. Yet speech disorders such as lisps, dysarthrias (unclear articulation) and stutters may become persistent and continue into adulthood. For a scientist, this can present real challenges. Grant applications, networking events and pitching your ideas verbally are all situations that require making a good first impression; for a scientist with a speech impairment, even routine tasks such as attending a conference or teaching students can represent a traumatic experience.

Reclaiming my name

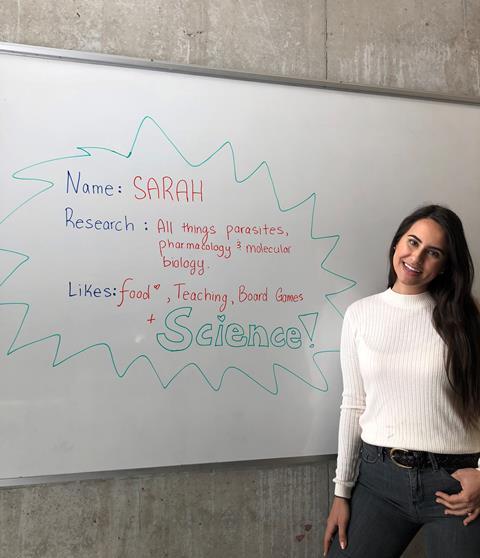

Sarah Abdelmassih, a PhD candidate at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Canada has had lisp for all her life. However, she noticed it brought her increased unwanted attention after joining her PhD programme. ‘Moving forward in academia involves talking to a wide range of people. This is where I got reminded about my lisp, because at least twice a year I have students approaching me after my talk to ask me: “Do you know you have a lisp?”’

Abdelmassih’s lisp has been causing difficulties inside and outside of the lab. ‘When I meet new people and introduce myself, they often think I’m saying Tara. This is the most difficult to deal with, because my own name is giving me a hard time on a daily basis. My solution is to draw an imaginary “S” in the air as I introduce myself to make it easier to understand.’

Although colleagues sometimes try to help, Abdelmassih says this is the exact opposite of what she needs. ‘I do not want to have other people stepping in to help me say my own name.’

Abdelmassih recently decided to widen her social media outreach and turned the camera around. She now regularly posts videos of herself explaining science to her followers and speaks at TEDx events. ‘I think that I became a stronger person due to my lisp – and that my social media helped me accept myself more.’

A quest for patience

Paul – not his real name – is a chemist based in Germany. He has been stuttering since he was a small child, often facing bullying and social exclusion. ‘It’s a strange feeling,’ he says. ‘In my brain I have the words exactly as I want to say them, I can see them in front of my eyes. But, somehow, I am not able to say them. They are blocked.’

Paul often has to travel to international conferences and networking events. His stuttering becomes much worse with increasing stress levels, meaning he finds these events especially troublesome. ‘If I have to stand in front of a crowd and make myself heard, including speaking up in a loud group, I freeze. When all attention is on me and I keep being interrupted, that’s when I start stuttering.’

Encounters with native English speakers are particularly problematic, Paul finds. Rather than give him space to finish the thought, he says colleagues often get nervous and finish the sentence or say the word for him. Rather than helping, this tends to make him feel embarrassed and stop talking. ‘What would be helpful is if people would wait for two seconds longer until they get an answer,’ he explains. ‘This would decrease my stress level, which could in turn improve my stuttering significantly.’

Accepting his disorder is a gradual and still ongoing process. Paul has been working hard on his presentation skills and started preparing monologues for his presentations.

However, Paul believes his disorder has had a significant impact on his career. ‘I feel like I have a big disadvantage during networking events. Looking for a new position is very difficult with a speech disorder such as stuttering. This could be affecting my future career, unfortunately.’

What you can do

There is no easy solution for speech disorders, says Anouck Visinand Ward, a speech therapist based in Switzerland. Instead, each disorder requires an individual therapeutic approach. However, there are simple techniques that others can do to help. For example, if a colleague has a lisp, it’s important not to interrupt, which may force them to repeat themselves. ‘In the case of stuttering, I encourage [people] to focus on their breathing when they are in contact with someone who stutters,’ Ward adds. ‘The breath of the person who stutters is altered at the time of stuttering and leads, by a mimicry phenomenon, to a blockage of the other speaker’s breathing. It is therefore essential to focus on one’s breath.’

But perhaps the most important advice is simply to be kind and polite. ‘In my experience,’ Ward adds, ‘one should continue with the interaction as one would with any other person.’ Do not highlight the person’s speech disorder, interrupt them or attempt to help. Instead, recognise the person and their ability – and show patience and understanding as they find their voice. You may be amazed at what they have to say.

No comments yet